Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Monday, 25 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In Part 1 of the article series on the Government’s Vision 2025 published last week (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Vision-2025--Part-1--Need-for-moving-from-a-wish-list-to-a-concrete-plan/4-639757), it was pointed out that the present vision document was just the fourth of such visions pronounced by the Government during the last two year period.

These documents which started from the election manifesto of the United National Party presented to the electorate in August 2015 had one underlying theme.

That was the new economic philosophy of the Government which was styled as ‘Knowledge-based Highly Competitive Social Market Economy’, a concept adapted from Germany which had introduced it after the Second World War. Germany’s vision had been to have a third way, different from the Western capitalism and Soviet Union’s communism which had been ruling the world at that time and proved to be ineffective to meet the aspirations of all the people in a country. Apparently, UNP too had felt that it needed a new ideology, different from the extreme state expansion policy which had been adopted by the previous Mahinda Rajapaksa administration.

However, it was pointed out in the previous article that three shortcomings in the first three policy statements, namely, lack of consensus among the ruling coalition parties on economic policy, failure to sell it to people and the Minister of Finance taking the country in the opposite direction, had hampered their proper implementation. Hence, the need of the day had been identified as translating the wish list in the vision into implementable concrete plans.

As pointed out previously, Vision 2025 has two time-bound goals, four intermediate goals to be realised by 2020 and one final goal to be achieved by 2025. The four intermediate goals have been to increase the average income of a Sri Lankan, also known as per capita income or PCI, from the present $ 4,000 to $ 5,000, generate one million jobs, increase foreign direct investments or FDIs to $ 5 billion per annum and double the country’s exports from the present $ 10 billion to $ 20 billion. The final goal has been to make Sri Lanka a rich country by 2025.

These are highly ambitious goals and, therefore, challenging. They are specially challenging given the high growth rates which the country has to achieve over the next eight-year period if it is to become a rich country.

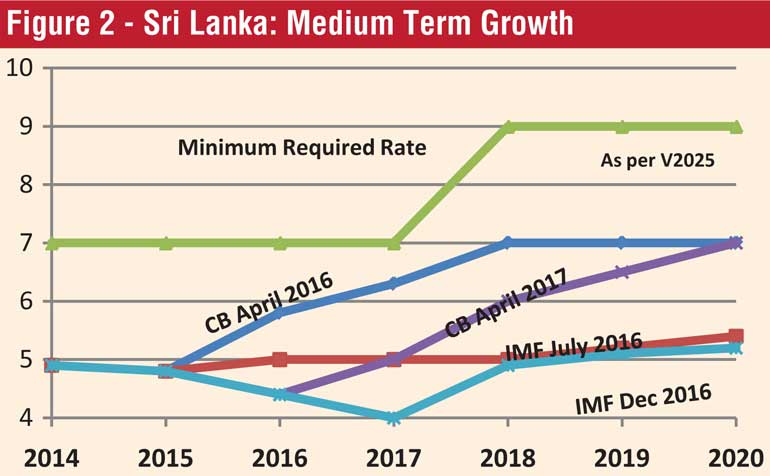

In the intermediate target of elevating Sri Lanka’s PCI to $ 5,000, the country has to maintain on average a continuous growth rate of 9% per annum in each of the years from 2018 to 2020. Similarly, to become a rich country by 2025, Sri Lanka should have a PCI of little over $ 12,000, according to World Bank’s classifications. That requires Sri Lanka to accelerate its growth rate to above 16% per annum during 2021 to 2025.

Sri Lanka’s efficiency of capita utilisation, known as Incremental Capital Output Ratio or ICOR, is so low that it has to on average use five units of capital to produce one unit of output. Thus, the annual investment requirement to attain the first target of 9% growth is about 45% of the total output, known as the Gross Domestic Product or GDP. In the latter target, it is an exorbitantly high level of about 80% of GDP.

To maintain such a high level of investment, Sri Lanka has to, in the first place cut down its consumption drastically, known to economists as ‘austerity measures’ or to laymen, as ‘belt-tightening measures’. However, there is a limit to such austerity measures which Sri Lanka can safely introduce, given the high preference for consumption by all, ranging from politicians to bureaucrats to common men and women.

If belts cannot be tightened sufficiently, no alternative but use savings of foreigners

Hence, there will still be a gap between potential savings and the required investments. That gap, known as the savings-investment gap, has to be filled by using savings done by people in the rest of the world. Those savings are mobilised by a country by making foreign borrowings or attracting FDIs or allowing foreigners to invest in the country’s securities market, known as portfolio investments or simply getting foreigners to give free gifts or grants or by using all of them. In the past, Sri Lanka had tried to fill the gap mainly by borrowing from abroad but it had increased the country’s foreign debt to unmanageable levels.

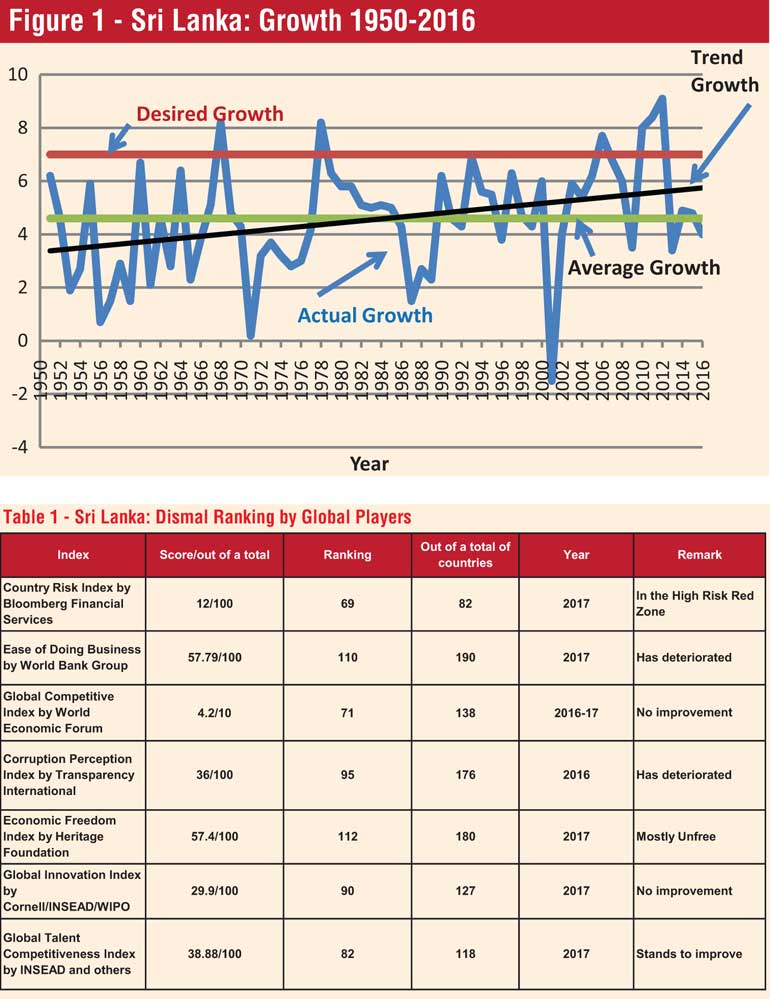

Sri Lanka’s past track record with regard to economic growth has also not been very encouraging. On average, during the whole of the post-independence period, Sri Lanka’s annual economic growth has been at around 4.4%, as shown by Figure 1. In the first half of 2017, its growth has been still worse at 3.9%. Though the authorities have expressed hope that there would a bounce-back in the second half of the year, all the available indicators such as agricultural production and growth of exports have shown that the country would finally end up at an average growth of 4% in 2017.

Though, in its latest projection, the Central Bank has expected that the growth rate would increase to 7% by 2020, as shown in Figure 2, the projection made by IMF has been significantly below that. In this scenario, the acceleration of the growth rate to a minimum of 9% per annum during 2018-20 and to 16% during 2021 to 2025 would certainly be an uphill task.

In the case of the three previous policy statements, Sri Lanka still planned to be a rich country but it had assigned to itself a very long date for attaining that goal, namely, 2045. But in the Vision 2025, that long date has been advanced to 2025, a kind of an acceleration of the growth momentum planned previously.

As pointed out in the previous article, this acceleration had nothing to do with the country’s perceivable economic cycles. Instead, it had been linked to the country’s election cycle in which there would be two Parliamentary elections one in 2020 and the other in 2025. The Government’s wish to secure victory at these two elections is understandable. But the goals which it has set for itself and for sale to the electorate have been too challenging for its built-in capability.

Sri Lanka’s annual domestic savings are on average at about 20% of GDP. This means that when a Sri Lankan living in Sri Lanka earns 100 rupees, he spends 80 rupees on consumption. This is comparably a high level of consumption, compared with high savers in the region like Singapore or China which have a savings record of about 50% of their income.

Sri Lanka’s domestic savings are being augmented significantly by the inflow of remittances by Sri Lankan workers abroad. These remittances constitute about 8% of GDP; thus, the country’s national savings which include such remittances as well have been recorded at a higher level of about 28% of GDP over the last few years.

However, remittances are not a source of funding on which Sri Lanka can make too much of dependence since they are subject to constraints. On one side, Sri Lanka cannot send people out for employment without experiencing a labour shortage within the country. On the other, the employing countries also cannot do so continuously due to domestic political and economic problems.

Hence, it is safe for Sri Lanka to rely on domestic savings rather than national savings to finance its target level of investments. But to do so, it has to force all Sri Lankans to cut their consumption at least by another 10% of GDP allowing the country to increase its domestic savings rate from the current 20% to 30%. However, it requires everyone – politicians, bureaucrats and ordinary citizens – to take a cut in the present welfare levels. The biggest challenge for the Government is to change the mindset of both politicians and bureaucrats to take this hit.

of investments. But to do so, it has to force all Sri Lankans to cut their consumption at least by another 10% of GDP allowing the country to increase its domestic savings rate from the current 20% to 30%. However, it requires everyone – politicians, bureaucrats and ordinary citizens – to take a cut in the present welfare levels. The biggest challenge for the Government is to change the mindset of both politicians and bureaucrats to take this hit.

However, even when the country’s domestic savings are increased to 30% of GDP through enforced austerity measures across the board, there will still be a sizeable savings-investment gap which has to be filled by using savings made by foreigners. Since the country is already in a foreign debt trap and the Government has made announcements that it does not want to increase these debt levels any more, the only available source has been the attraction of FDIs. In the intermediate targets set in Vision 2025, the Government wishes to increase FDIs from the present less than $ 1 billion to $ 5 billion by 2020. Based on the track record of the country, this is again an uphill task.

What will go against the Government’s desire to attract FDIs is the general inefficiency of the public sector in the country, unpreparedness of the private sector for the changing global environment and the indecision of the political leaders. This has been demonstrated by Sri Lanka’s very low ranking in all the global indexes, as presented in Table 1. This is not a new development and the country had always been ranked low by those agencies even in the past.

When these reports were out, the reaction of the previous Mahinda Rajapaksa administration was that those compiling agencies were biased, prejudiced and vindictive and were carrying on a mission to destroy Sri Lanka’s bright future.

Hence, every time a new index result was out, there were angry retorts and promises of compiling Sri Lanka’s own indexes to represent its true state to the rest of the world. However, they were only promises and none of these homemade indexes was release subsequently.

The result was that Sri Lanka could not attract worthwhile FDIs even after the end of the war when there was a lot of promise for such investments to take place. For instance, during 2005 to 2009, according to the Central Banking data, Sri Lanka had got on average an annual flow of FDIs amounting to $ 644. This number has slightly increased to $ 793 million during 2010 to 2014.

New Government’s track record of attracting FDIs is not better than previous Government

When the new Government came to power in January 2015, the promise of Sri Lanka as a destination of worthwhile FDIs was substantially increased on account of the pledge it had given to the rest of the world that it would usher an era of good governance, transparency, rule of law and law and order. Yet, FDIs it could attract during 2015 and 2016 amounted, on an annual average, only to $ 789 million, almost same as the country’s record during the previous post-war period.

Even then, during the two periods under reference, those FDIs were mainly for the hospitality and real estate sectors, and not for high tech industries that could have revolutionised the country’s production structure, the need of the day.

The present Government was expected to take measures to improve the country’s standing on these indexes. But no action was taken for two years and the country’s standing deteriorated further during that period. Now that the Government is planning to accelerate economic growth to a very high level during the next eight-year period and it plans to depend principally on FDIs, it cannot ignore the falling standing of the country in the eyes of foreign index compiling agencies.

An important intermediate target of the Government during 2018-20 has been the generation of one million jobs. Vision 2025 claims that from January 2015 up to date 430,000 new jobs have been created within the economy.

However, this claim is not being borne out by the data that have been published by the Central Bank in its Annual Reports based on the data compiled by the Department of Census and Statistics. According to the Central Bank, as at the end of 2014, the number of people employed in the country had amounted to 8.424 million. As at the end of 2016, this number has declined to 7.948 million recording a decline of employment by 476,000.

What it means is that if the Government’s objective is to create one million jobs over the level of employment that had prevailed at end 2015, it has to create nearly 1.5 million new jobs during 2018-20. This is again an uphill task.

Vision 2025 plans to double exports from the current level of $ 10 billion to $ 20 billion by 2020. The next part will examine the nature of the challenge faced by the Government to attain this goal within a mere three-year period and the policy package it should implement if it is willing to adopt a long date for attaining that target.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)