Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 8 December 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Without even being a large consumer of plastics globally, Sri Lanka generates more than 5 million kilograms of plastic waste per day, where the per capita daily contribution is nearly 0.5 kg – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Ruwan Samaraweera

The lockdowns introduced in 2020 to curb the spread of COVID-19 saw the narrative ‘nature is healing’ gain prominence. However, the notion that nature, in the absence of people, was healing fizzled out fairly quickly with the emergence of fresh environmental challenges, most notably, the resurgence of single-use plastics.

prominence. However, the notion that nature, in the absence of people, was healing fizzled out fairly quickly with the emergence of fresh environmental challenges, most notably, the resurgence of single-use plastics.

In fact, in the months following the lockdowns, reliance on plastics grew exponentially, with the scale of the negative environmental impacts far outweighing initial gains such as reduced air and noise pollution. This blog examines the ecological fallout of the pandemic and suggests policy options for Sri Lanka to avert the looming environmental disaster.

The plastic pandemic

Plastics have several applications and offer undeniable benefits to consumers and producers due to specific, inherent properties. They are hygienic, lightweight, flexible and anti-corrosive. As such, plastics are among the most extensively-produced material globally with 359 million tonnes of plastics produced in 2018 alone. However, plastics have become a severe environmental concern due to haphazard disposal. Plastics include consumables like plastic bags, straws, cups, bottles, etc., which are thrown away after being used just once, referred to as single-use plastics. Worldwide consumption of plastic bags ranges from 1 to 5 trillion annually, and almost 160,000 plastic bags are consumed per second globally.

Without even being a large consumer of plastics globally, Sri Lanka generates more than 5 million kilograms of plastic waste per day, where the per capita daily contribution is nearly 0.5 kg. Sri Lanka is already struggling to cope with the amount of plastic waste generated each year. Unless concrete measures are taken to alter the current manufacturing methods and consumption patterns of plastics, the situation could result in irreversible damage to the environment. The global threat of the COVID-19 pandemic makes the problem (ex: Styrofoam, aluminium cans, polystyrene, etc.) even more challenging.

plastic waste per day, where the per capita daily contribution is nearly 0.5 kg. Sri Lanka is already struggling to cope with the amount of plastic waste generated each year. Unless concrete measures are taken to alter the current manufacturing methods and consumption patterns of plastics, the situation could result in irreversible damage to the environment. The global threat of the COVID-19 pandemic makes the problem (ex: Styrofoam, aluminium cans, polystyrene, etc.) even more challenging.

An ugly resurgence

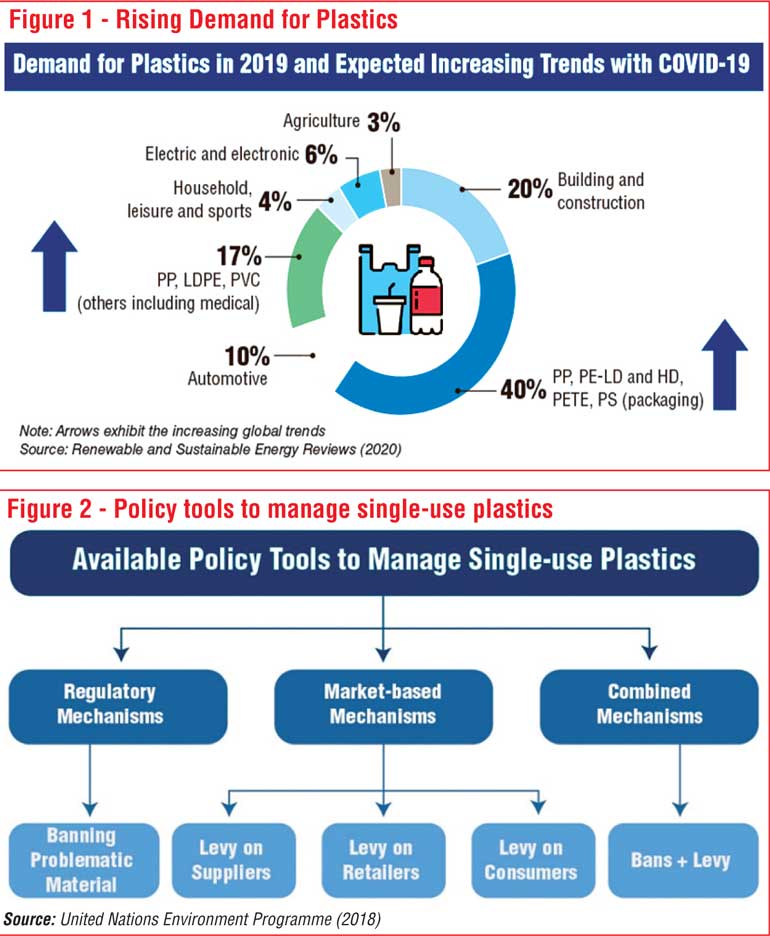

The demand for plastic by medical and packaging sectors is increasing sharply compared to pre-pandemic conditions (Figure 1). For instance, an estimated 89 million medical masks, 76 million gloves and 1.6 million goggles are required monthly in the battle against the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). As a result, researchers expect a 53.4% market growth for disposable facemasks over 2020-2027. The disposable facemasks are produced using polymers such as polypropylene (PP), polyurethane, polyacrylonitrile, polystyrene, polycarbonate, polyethylene (LDPE), or polyester, which are potential sources of microplastics.

Estimates illustrate that the demand for disposable syringes and plastic containers that store vaccines will be increased with nationwide vaccination efforts against COVID-19. As a result, the global market will experience a 7% compound annual growth rate and reach a value of USD 14.4 billion by 2030. Moreover, the demand for other personal protective equipment like face shields made from PP, LDPE gowns, vinyl gloves made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) will increase sharply along with the plastic packaging material. Thus, the production and consumption of PP, LDPE and PVC material will exhibit an increasing trend.

Lockdowns and resulting online shopping and home delivery can escalate the demand for plastic, which is reflected by the accumulation of plastic wastes, especially from food packaging. In Thailand, plastic waste rose by 15% during the pandemic, primarily due to food packaging waste, resulting from tripled food delivery demand. During the pandemic, many governments worldwide banned the use of reusable cups and food utensils due to safety reasons since reusable commodities could be contagious. Scholars also predict a drastic increase in medical waste that includes single-use plastic and other environmentally problematic material.

For instance, in Hubei province, China, medical waste generation increased sharply, and by 9 March 2020, the country collected 468.9 tonnes of medical waste related to the pandemic. A more significant proportion of that waste is comprised of single-use plastics. Wuhan’s medical waste exceeded the maximum incineration capacity of 46 tonnes/day due to a dramatic rise in waste accumulation up to 240 tonnes/day. Hence, despite their detrimental impacts, managing the pandemic is linked with single-use plastics and other environmentally-harmful material.

The way forward

Addressing environmental, economic, health, and socio-cultural issues related to single-use plastics and other damaging material requires identifying the most problematic single-use plastic and other material, evaluating the scale of the problem, identifying significant sources of pollution and potential impacts of mismanagement on the environment, human and animal health, and the economy. Various methods can reduce the harmful effects of single-use plastics and other environmentally problematic materials. However, the availability of alternatives is crucial to cut down the use effectively.

Voluntary reduction strategies

One of the key instruments for single-use plastic is voluntary reduction strategies. Those are based on consumption patterns, consumer and producer choices upon an increased understanding.

Awareness creation

Voluntary adjustments are facilitated by awareness creation among stakeholder groups which are a gradual and transformational process that changes consumer and producer behaviour.

Policy instruments

Policy instruments can be classified as regulatory and economic (market-based and a combination of regulatory and financial) instruments.

The principal legislation governing plastic pollution in Sri Lanka is the National Environmental Act No. 47 of 1980, where Section 32 comprises the manufacture, sale and use of plastic and polythene. As previously mentioned, several amendments were made to the act to address the challenges in managing plastic waste. Lobbying from local industry and pressures from major exporting countries, and availability of alternatives remain significant challenges in implementing bans. However, as discussed earlier, single-use plastics have the lowest recyclability and highest disposable rates. Therefore, implementing a combined approach of levies, bans, and extended producer responsibility (EPR) wherever necessary would enhance the positive impacts.

(Link to blog: https://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/2021/12/07/plastic-pandemic-the-ecological-fallout-of-covid-19-and-policy-options-for-sri-lanka/)

(Ruwan Samaraweera is a Research Officer at IPS, with a background in entrepreneurial agriculture. He holds a Bachelor’s in Export Agriculture from Uva Wellassa University of Sri Lanka. His research interests are in environmental economics, agricultural economics, macro-economic policy and planning, labour and migration, and poverty and development policy. (Talk to Ruwan – [email protected].)