Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 12 April 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Avurudu falls on 14 April Sunday this year. On this day at 2:09 p.m., the sun crosses an imaginary line that separates the constellation Pisces from Aries, marking the dawn of the Sinhala and Tamil New Year.

The period from 7:45 a.m. to 2:09 p.m. is the Nonagathe period where you are not supposed to eat or do any work, but engage in reflections and/or religious activities. The Active period is from 2:09 p.m. onwards. Prescribed time for the first-meal in the ‘New Year’ is 3:54 p.m.

I am thinking of doing a big breakfast of leftovers from ‘last year’ before the Nonagathe begins at 7:45 a.m. and waiting for the auspicious time. Alternatively, you can do whatever you do, and have a festive ‘high tea’ with kiribath and traditional sweets so that you are in sync with the rest of the country.

I don’t believe in astrology, but I take Avurudu seriously because this is one day when we can bridge many divides in our society and almost all of us eat the same thing at the same time. The starch-heavy diet makes you feel sleepy and appreciate that you do not eat in this style the rest of the time.

Astrology and astronomy

Viewed from the earth, the sun’s disc takes 12 hours and 48 minutes to cross an imaginary line in the sky. The astrological New Year marks the crossing of the imaginary line which separates the astrological positions of the constellations Pisces and Aries (the actual positions have changed over time).

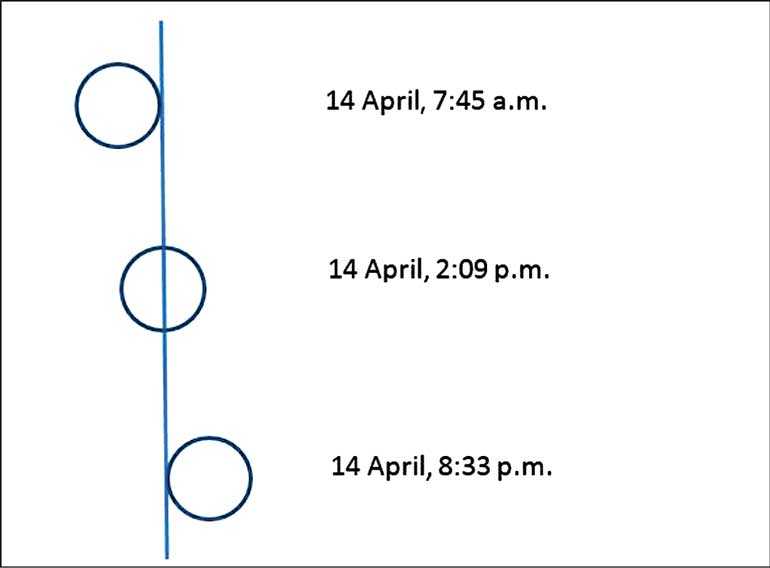

For 2019, the sun begins this transition on 14 April at 7:45 a.m. and completes the transition at 8:33 p.m. the same day. This transition period of 12 hours and 48 minutes duration is called the Punya Kalaya. The midway point at 2:09 p.m. is the dawn of the New Year.

The first half of the transition period is the do-nothing or the Nonagathe period. When we were children, the hearth was cleaned of all the ashes and the last bucket of water was drawn from the well to prepare for the Nonagathe. No work, not even reading and writing, was allowed except for a trip to the temple.

We waited in anticipation for the end of the Nonagathe and the beginning of the second half when up in the sky, the sun’s disc would be centred on the imaginary line. As soon as that time arrives, as told to us by astrologers, fire crackers start to signify the dawn of the New Year. For 2019, the dawn of the New Year at 2:09 p.m. is exactly six hours and 24 minutes after the beginning of the transition.

The second half is the active period. Astrologers prescribe the times to draw the water from the well, light the fire, cook the food and eat the food, using some obscure calculations. It would be better if we divide the time for each task according how long each would take, but then astrologers would be jobless.

For 2019, the prescribed time to start cooking is 2:42 p.m. The time to eat is set at 3:54. They also suggest you eat kiribath and mung kavun for the occasion. You don’t have to buy into the phony calculations to enjoy one time of the year when we all over-indulge on the same food at the same time.

What we ate then and now

Traditional meals are in some ways frozen in time. The Avurudu meal is exceptionally heavy on starch. An additional bit of protein comes from the Maldive fish in the lunu miris. Did Sri Lankans eat a lot more starch than accompaniments in the old days?

According to the Household Income Expenditure Survey of Sri Lanka, the amount of rice a household consumed went down from 46.7 kilos per month in 1980 to 34.8 kilos per household in 2016. Household size went down from 4.9 to 3.9. Rice is still very important because amount per person increased from nine to 12 kilos per month. However, people are now eating more meat, fish and milk products.

Households increased their consumption of meat from 0.8 kilos per month to 1.6 kilos, but increased the consumption of fish only marginally from 3.5 kilos per month per family to 3.7. Consumption of dried fish went down from 1.4 to 1.2, I am sad to notice.

The data is not broken down by income group, but the well-to-do would be eating much less rice and more accompaniments.

Eat together and stay together?

They are many adages about eating together. The family that eats together stays together is my favourite. Another one we might add is that a country that eats together stays together. Here I don’t mean the familiar ethnic divide. I am thinking more of the Westernised/non-Westernised divide.

There was a time when the Sinhala elite thought it beneath them to eat rice and curry. Once I was shocked to hear that in the 1930s before independence, an elite Sinhala family from the south would have rice and curry only on Sundays. The rest of the days they ate courses, whatever that meant.

There seems to be more genuine interest in rediscovering traditional food now, perhaps due to the need to distinguish ourselves in an increasingly-connected world.

(A similar column was published for Avurudu 2016.)