Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 26 April 2019 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

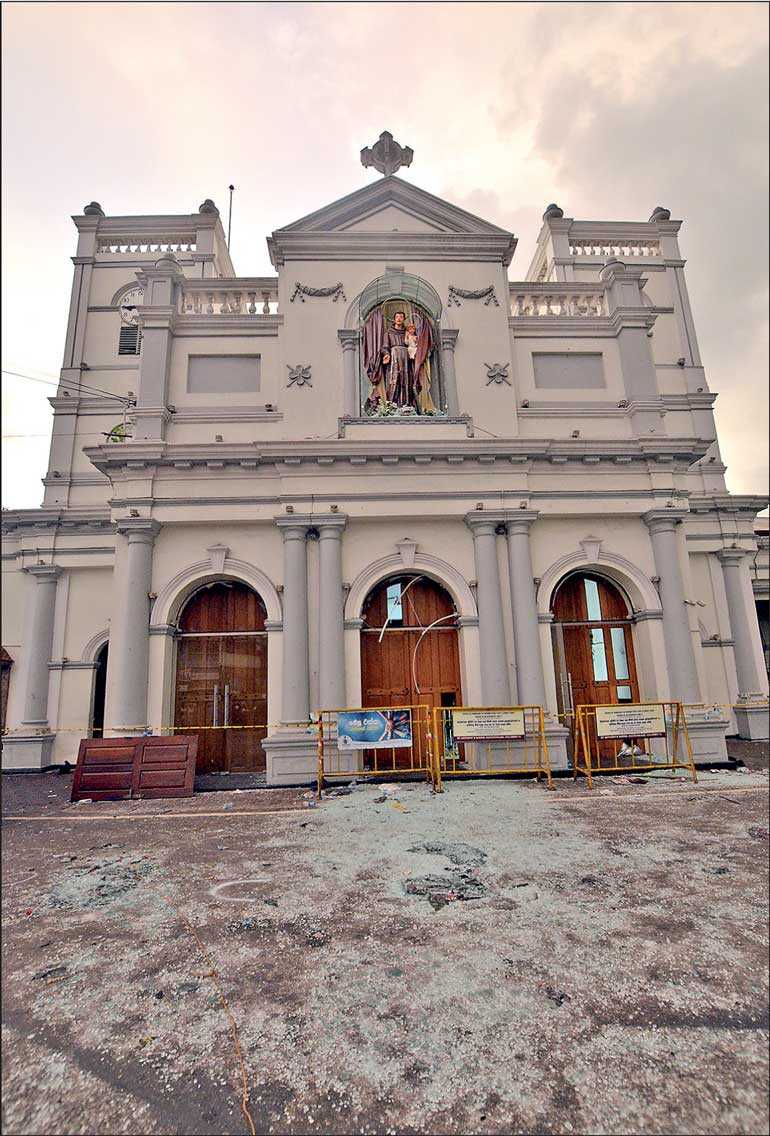

The heart is heavy and the pen is slow. The environment is thick with the shared sorrow of many. Pain and suffering caused by deaths of hundreds and maiming of more on Easter of 2019 will linger for the rest of our lives. But life must go on and we must take back our public spaces from religious extremists. How do we do that without infringing on our collective rights is the question.

Strengthening anti-terrorist laws is on the agenda. I won’t comment on those at this point. A bill to ban the full face covering burkha or the niqab is also proposed and that interests me. However, I would not advocate the banning of a particular garment, but argue for the forbidding the regular practice of covering one’s face in public places. In fact, we should not be targeting specific issues or specific communities – though the effect can be such – but look at the whole issue of safety and well-being of citizens in public space and their ability to participate in democracy.

I define public spaces not only as physical spaces but laws, regulations, customs, etc. that affect each of us with no ability on our part to control them. It would be both imprudent and impractical to exclude religion from public spaces. But I would argue we should aim at making public spaces as secular as possible if we are to keep them safe and welcoming for all citizens and to ensure democracy in our country.

Recent attacks have manifested the ability of Islamic extremists to invade the public sphere to kill and maim. With religious texts subject to interpretation, it is difficult to judge where religious fundamentalism ends and extremism begins. Therefore, it is in our common interest to deter fundamentalist practices in the public sphere while recognising that individuals are free to practice their religion as they see fit in their private spaces.

I would start with issues of child marriage and the face-covering burkha or the niqab garments. I will also look at the noise pollution of airwaves with religious chanting, a malpractice common to all religions. I would argue for legislation to counter these within a broader framework secularity in the public space as being essential to reduce fundamentalist tendencies in society and their threat to democracy.

One law for all

Recent attempts to enforce the marriage age to all communities including Muslims met with resistance from some Muslims led by the terror group National Thowheed Jamaath which has now claimed responsibility for Easter attacks.

The present tragedy presents an opportunity to bring legislation to bring Sri Lankans under the same marriage law, abolishing all other marriage laws including Muslim, Tamil Thesavalame or Up-country laws. Underage marriages will not be allowed for any religious community. This is an essential first step in recognising that we are all equal under the law and in the public space of which the legal framework is a part.

Right to see and responsibility to be seen in public places

I personally find the sight of women in burkha or niqab offensive. While I admire the elegance of the hijab or the veil covering the hair and the flowing garments that accompany the veil, the black ghosts with covered faces bring up a fury inside me which I have been struggling to control. These women have a right to choose their clothing my logical mind would tell me, but unconsciously the anger rises.

A lot has been written about face covering garments in regard to rights of women vs. community standards and so on. However, I am yet to see an argument based on the right to see and judge a person in a public space. Overtime, we have evolved the ability to gauge a situation by a simple gesture or demeanour of another. It is essential for the survival of the species I am sure. A deeper discourse in this regard is need, but I feel we need legislation to assure the rights of citizens to receive sufficient information to judge the safety of a particular space including the demeanour of fellow occupants of that space.

Special permission for public chanting

One phenomenon that signifies the harmful invasion of public spaces by religions is the battle over airwaves in Central Colombo. Having moved to the city a decade ago, initially I enjoyed rising in the morning to the call to prayer from mosques. Irrespective of the religious difference, I found the melodic call to prayer a soothing reminder of the spiritual side of life. But, over the years the sound got louder and it got to be a disturbance.

Not to be outdone, the Buddhist temples in the vicinity started responding with louder chants and tom-tom beating katina processions on workdays starting at 4 a.m. or before. Visiting Kattankudy in the Eastern Province once I was awakened in disbelief by a duel over the airwaves between a kovil and a mosque. Now my response is ‘tone it down, all of you’.

We already have laws to curtail noise disturbances after a certain time in the evening. Those need to be strengthened to include the use of loudspeakers for religious events including the daily chanting of pirith or call to prayers. A circular defining decibel levels has to be resent to all police stations so that only those attending an event are able to hear a pirith chanting. Calls to prayers should be limited to what each mosque can achieve with human vocal chords.

Religious processions and festivities add to our urban life, but there should be a public calendar in each local authority area marking those events. Anything outside those should be conducted under license. Poya days and Ramadan, Shiva Rathri and other numerous special days can be included, but only at specific times at specific locations.

Nudging not sufficient, legislation needed

In a previous column I argued that “our leaders and civil society should keep nudging each community one small step at a time while giving all parties the signal that the concerns of each are valid,” but times have changed. The difference between fundamentalism and extremism is a thin line. We should do everything possible to discourage fundamentalism in our society and bring all citizens together as Sri Lankans first.

Public discourse takes time. Nudging too takes time. Legislation has to be enacted now. We don’t need a law to ban the burkha, but an anti-terrorist law perhaps could include a clause to require that anybody occupying a public space (or a space outside private ownership) makes his/her face open for observation so that law enforcement officials as well as ordinary citizens are able to judge dangerousness or the hostility level of a given environment.