Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 14 May 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

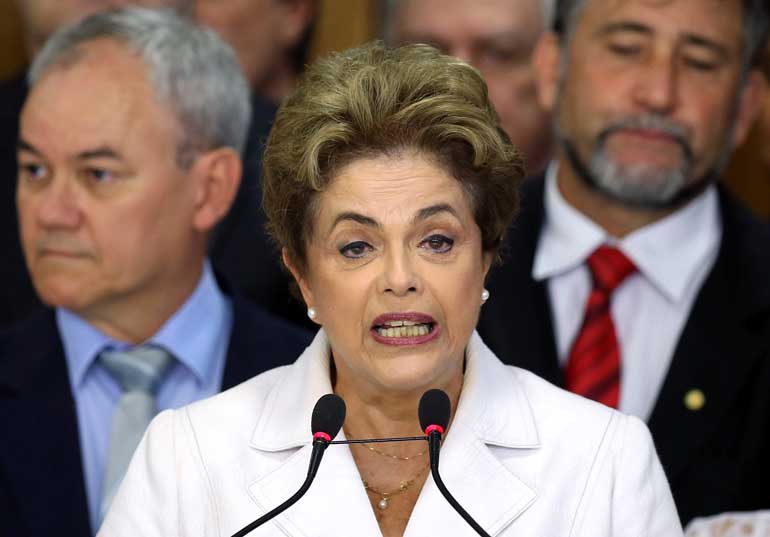

Suspended Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff addresses the audience after the Brazilian Senate voted to impeach her for breaking budget laws, at Planalto Palace in Brasilia, Brazil, May 12, 2016. REUTERS

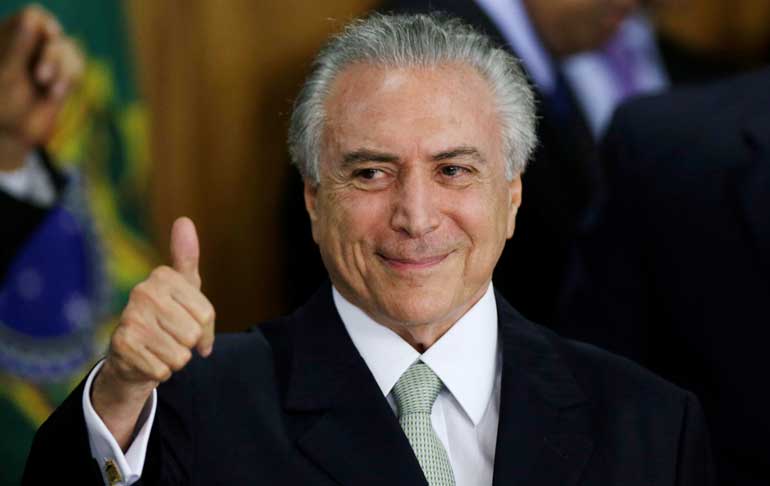

Brazil’s interim President Michel Temer gestures during a ceremony where he made his first public remarks after the Brazilian Senate voted to impeach President Dilma Rousseff, at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, Brazil, May 12, 2016. REUTERS

Reuters: Brazil’s interim President Michel Temer called on his country to rally behind his government of “national salvation,” hours after the Senate voted to suspend and put on trial his leftist predecessor, DilmaRousseff, for breaking budget laws.

Temer, a 75-year-old centrist now moving to steer Latin America’s biggest country toward more market-friendly policies, told Brazilians to have “confidence” they would overcome an ongoing crisis sparked by a deep economic recession, political volatility and a sprawling corruption scandal.

“It is urgent we calm the nation and unite Brazil,” he said, after a signing ceremony for his incoming cabinet. “Political parties, leaders, organisations and the Brazilian people will cooperate to pull the country from this grave crisis.”

Brazil’s crisis brought a dramatic end to the 13-year rule of the Workers Party, which rode a wave of populist sentiment that swept South America starting around 2000 and enabled a generation of leftist leaders to leverage a boom in the region’s commodity exports to pursue ambitious and transformative social policies.

But like other leftist leaders across the region, Rousseff discovered that the party, after four consecutive terms, overstayed its welcome, especially as commodities prices plummeted and her increasingly unpopular government failed to sustain economic growth.

In addition to the downturn, Rousseff, in office since 2011, was hobbled by the corruption scandal and a political opposition determined to oust her.

After Rousseff’s suspension, Temer charged his new ministers with enacting business-friendly policies while maintaining the still-popular social programs that were the hallmark of the Workers Party. In a sign of slimmer times, the cabinet has 23 ministers, a third fewer than Rousseff’s.

A constitutional scholar who spent decades in Brazil’s Congress, Temer faces the momentous challenge of hauling the world’s No. 9 economy out of its worst recession since the Great Depression and cutting bloated public spending.

He quickly named respected former central bank governor Henrique Meirelles as his finance minister, with a mandate to overhaul the costly pension system.

The Senate deliberated for 20 hours before voting 55-22 early on Thursday to put Rousseff on trial over charges that she disguised the size of the budget deficit to make the economy look healthier in the runup to her 2014 re-election.

Rousseff, 68, was automatically suspended for the duration of the trial, which could be up to six months. Before departing the presidential palace in Brasilia, a defiant Rousseff vowed to fight the charges.

In her speech, she reiterated what she has maintained since impeachment proceedings were launched against her last December by the lower house of Congress. She denied any wrongdoing and called the impeachment “fraudulent” and “a coup.”

“I may have made mistakes but I did not commit any crime,” she said.

Rousseff’s mentor, former President LuizInacio Lula da Silva, who now faces corruption charges, stood behind her and looked on dejectedly. Even as outgoing ministers wept, Rousseff remained stolid.

“I never imagined that it would be necessary to fight once again against a coup in this country,” Rousseff said, in a reference to her youth fighting Brazil’s military dictatorship.

“This is a tragic hour for our country,” said Rousseff, an economist and former Marxist guerrilla, calling her suspension an effort by conservatives to roll back the social and economic gains made by Brazil’s working class.

The Workers Party rose from Brazil’s labor movement in the 1970s and helped topple generals who had held power for two decades ending in 1985.

Despite Rousseff’s vows to fight, she is unlikely to be acquitted in the Senate trial. The size of the vote to try her showed the opposition already has the support it will need to reach the two-thirds majority required to remove her definitively from office.