Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 14 December 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

From left: United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, French Foreign Affairs Minister Laurent Fabius, President-designate of COP21, and French President Francois Hollande applaud during the final plenary session at the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) at Le Bourget, near Paris, France, 12 December – REUTERS

By Charnika Imbulana in Paris

By Charnika Imbulana in Paris

The atmosphere of the Paris Convention Centre Hall at Le Bourget airport, on Saturday 12 December night could be described in just one word – euphoric. Delegates from nearly 200 nations cheered and embraced each other as the global consensus was reached known now as the ‘Paris agreement’ and no sooner announced by French Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius with the bang of the gravel to cement the deal, just before 7:30 p.m. Paris time on Saturday that it’s formally adopted.

Paris outcome is indeed a historic milestone to have reached with experts of almost 196 countries working together to reach a consensus in the last two weeks – and deserved the standing ovation the announcement of the landmark deal received. For the first time The Paris Agreement will require virtually every country in the world to set out its plans to avert climate change every five years.

US Secretary of State John Kerry called it a tremendous victory for all of our citizens ... It is a victory for all of the planet and for future generations . . . I know that all of us will be better off for the agreement we have finalised here today,” he said on Saturday.

But Edna Molewa, South African environmental minister and chair of the G77 and China group of emerging market nations, was more cautious: “The deal is not perfect . . . but the best we can get at this historic moment.”

Indian Environment Minister Prakash Javadekar hailed the accord. “Today is a historic day, it is not only an agreement, but we have written a new chapter of hope in the lives of 7 billion people on the planet.”

“Milestone in the global efforts to respond to climate change,” even if it was not perfect and contained ‘some areas in need of improvement’ said Xie Zhenhua, China’s chief climate negotiator hailing the agreement.

Nur Masripatin, lead negotiator for Indonesia, said Jakarta was disappointed with the finance. “It’s very weak,” he said. “The deal is not fair . . . But we don’t have more time, we have to agree on what we have now.”

The Australian Foreign Minister speaking after the declaration described it as a framework for all nations to play their part in climate change. “Our job is done, we go home now to implement as per the national circumstances and capabilities.” The document was tinkered with, even spilling well over 24 hours, after the deadline.

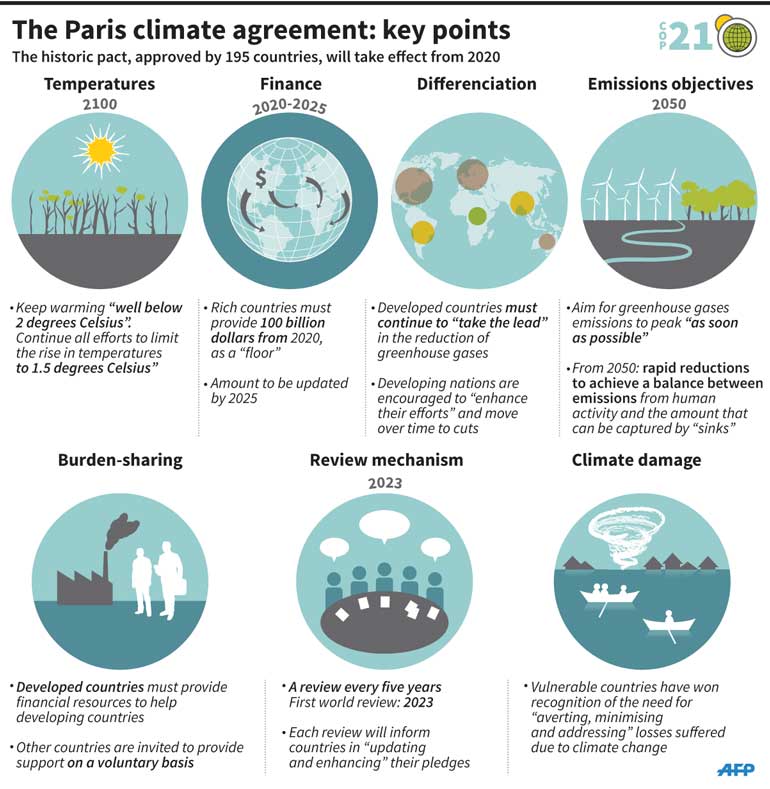

The key areas of the Paris Agreement could be categorised into the following:

A long-term goal to limit global warming to 2C, or 1.5C if possible

The Paris Agreement includes an objective to limit global warming to ‘well below 2C above pre-industrial levels’ and ‘pursue efforts’ to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C.

To meet these temperature targets, the draft says countries should aim to reach a ‘global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions’ as soon as possible and ‘achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century’ – in other words, net carbon emissions to be zero.

Scientists explained what it suggested that after 2050, countries could not emit more carbon dioxide – the greenhouse gas produced by burning fossil fuels – than could be absorbed by forests and other carbon ‘sinks’.

To get there, countries should aim to ‘reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, recognising that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties, and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science’.

National pledges to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the 2020s

The pledges countries have made already, the so-called ‘Intended Nationally Determined Contributions’ (INDCs) – pledges setting out how they plan to limit their greenhouse gas emissions during the 2020swill become Nationally Determined Contributions at the time each country ratifies the Paris Agreement and the proposed deal commits countries to ‘pursue domestic mitigation measures with the aim of achieving the objectives’.

Some 158 submissions covering 185 countries (the European Union submits one pledge covering all its member states) and covering more than 90% of global emissions have been made before and during the Paris summit.

A review of plan every five years to make countries pledge deeper emissions cuts in future

A key part of the deal is therefore the mechanism designed to make countries pledge deeper emissions cuts in future since the emissions cuts pledges made so far still leave the world on track for at least 2.7C warming this century. It requests the countries to come back before 2020 to revisit the pledges and to make new every five years, although this is not binding. The binding deal – covering the period after 2020 – also commits countries to ‘communicate a nationally determined contribution every five years’. Each country’s pledge must ‘represent a progression’ on their previous one ‘and reflect its highest possible ambition’.

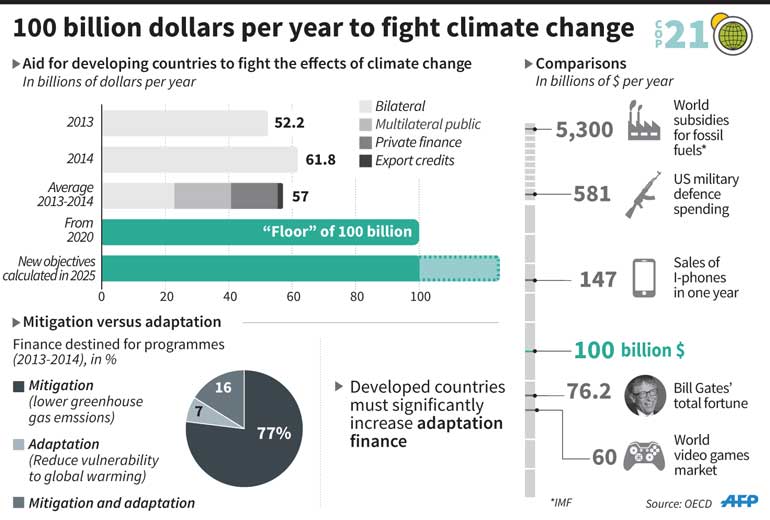

Rich nations to provide funding to poorer ones – ‘mobilising’ $ 100 billion a year until 2025, and more thereafter

As defined by the UN Framework in 1992 the agreement requires that ‘developed’ nations – will continue to help developing countries with the costs of going green, and the costs of coping with the effects of climate change. Currently, developed countries are obliged to ‘mobilise’ $ 100 billion a year of public and private finance to help developing countries by 2020 – a target set in Copenhagen in 2009. The Paris decision says they ‘intend to continue their existing collective mobilisation goal through 2025 – in other words continue the $ 100 billion a year, and then by 2025 set a new goal ‘from a floor of $ 100 billion’.

How much money the rich nations should give is now been moved into the non-legally binding ‘decision text’.

Developed nations meanwhile have been arguing for an end to the crude 1992 definition – which sees six of the 10 wealthiest counties in the world classed as ‘developing’ and under no obligation to contribute.

They were pushing for a wording suggesting other countries ‘in a position to do so’ should also contribute (especially as some, such as China, already are in practice). But developing nations resisted this wording and in the final agreement there is a much weaker commitment that non-developed nations are ‘encouraged to provide or continue to provide such support voluntarily’.

Thus Finance was one of the biggest rows of the talks, with developing nations demanding more cash (and arguing that developed nations haven’t even met their $ 100 billion pledge). Although many poorer countries wanted increased finance to be a legally-binding requirement, the US made it clear it would never ratify such a deal.

A plan to monitor progress and hold countries to account

In 2023, and every five years thereafter, there will be a global stock-take to assess progress toward the aims of the agreement and to encourage countries to make deeper pledges for a new transparency framework and hold them accountable of their pledges made.

Countries will have to be transparent and disclose an inventory of their emissions and information to track their progress in hitting their national target, while developed countries should also give information on the finance they are providing or mobilising. They will be subject to a ‘technical expert review’ and the transparency framework will have ‘built-in flexibility’ ‘that need it in the light of their capacities’ offered as a leeway to developing countries.

While this 31-page Paris Agreement of nearly 200 countries is indeed a momentous breakthrough, once the initial euphoria dies down, the delegates once back in their respective countries will have to take all the herculean steps into implementing as required by their countries in keeping to the agreement.

President François Hollande became the first leader to act on the new agreement, committing France to a revision of its national climate targets before 2020. He said the country would ‘work with all parties who want to scale up ambition pre-2020’, and that he would also form a coalition of countries on carbon pricing.

Many businesses hailed the Agreement as a significant step. Stuart Gulliver, Chief Executive of the HSBC banking group is quoted to have said “We welcome the Paris outcome as a historic milestone on the road to a more sustainable global economy,” Paul Polman, chief executive of Unilever had praised the agreement as ‘an unequivocal signal to the business and financial communities’ that would drive real economic change.

“The billions of dollars pledged by developed countries will be matched with the trillions of dollars that will flow to low-carbon investment,” he said, predicting the move by hundreds of businesses to shift to 100% renewable energy would ‘become the norm for hundreds of thousands’.

While dozens of environmental groups welcomed the pact, some expressed reservations.”This climate deal falls far short of the soaring rhetoric from world leaders less than two weeks ago,” said Craig Bennett, chief executive of UK campaign group Friends of the Earth, referring to the heads of state who opened the two-week Paris meeting on November 30.

“An ambition to keep global temperature rises below 1.5C is all very well but we still don’t have an adequate global plan to make this a reality. However, this is still a historic moment. This summit clearly shows that fossil fuels have had their day.” Among the points mentioned in the document is the nations’ “recognising that climate change represents an urgent and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet and thus requires the widest possible cooperation by all countries.” This they did.

However it is the South African delegate who described the situation the best, reflecting on the uphill task yet looming large with the implementation process of the latest climate change Paris Agreement, a reality check amidst the euphoria, quoting Nelson Mandela, she said ending her well written out speech:

“I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can only rest for a moment, for with freedom come responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not ended.”