Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 13 November 2015 00:11 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shanika Sriyananda

Shocked and terrified when she heard that she was going to marry soon, Srimathi, who was in her early 20s, kept crying incessantly. The youngest in a family of five, she used to live a carefree life but cried for days wondering how she could be the wife of a revolutionary leader since she was still an immature young girl.

With just a month left to tie the knot with a man who was behind bars for leading the 1971 youth insurrection, she was helpless to say a word against the ‘forced marriage’ arranged by her brother – Dr. Chandra Fernando.

Nothing could melt her brother’s heart and he threatened everyone who was against the marriage. Hailing from a highly-religious Methodist Christian family, Srimathi yearned for God’s intervention to stop the marriage as she was scared of languishing in jail with his future husband – one of the most infamous men in 1970s.

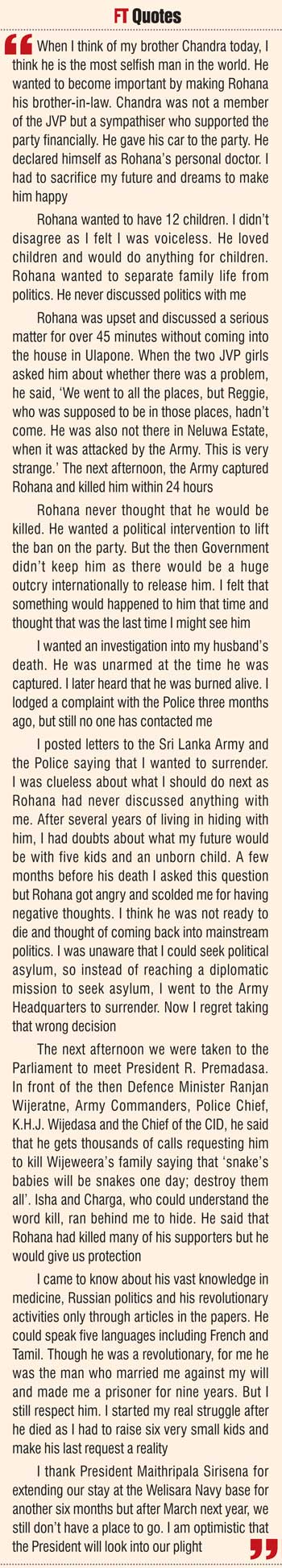

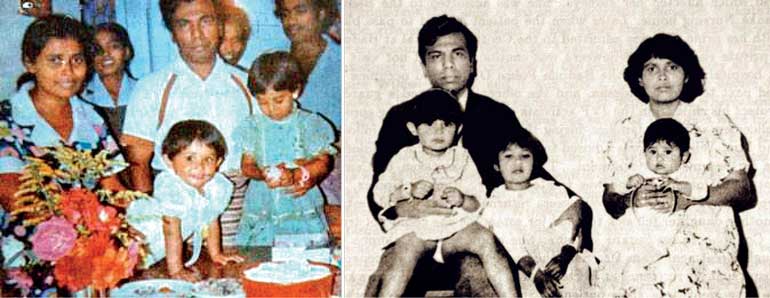

No miracles happened. On 26 March 1980, the 23-year-old Srimathi Chithranagani Fernando married Patabendi Don Nandasiri Wijeweera, who was 13 years older to her, at a simple family function held at her home in Wilorawatta, Moratuwa.

Living with a revolutionary

In an exclusive interview with the Daily FT, Srimathi, the widow of late Founder Leader of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), unfolded her plight of living with a revolutionary and his last days before he was killed in custody during President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s regime.

Politics was in her blood as his father S.V. Fernando – an English literature and physics teacher, was involved in politics through the Socialist Party and was once the Vice Chairman of the Moratuwa Urban Council.

H.N. Fernando, Srimathi’s elder brother, who was the Secretary of the Sri Lanka Teachers’ Union, had met Wijeweera in 1969 in Trincomalee and continued his connections with Wijeweera. He was also arrested during the JVP insurgency. Her second brother Dr. Chandra Fernando didn’t have any connections, but Srimathi says he was arrested as someone in the Ratnapura Hospital, where he was working, had tipped off his name as a JVPer in an act of revenge for exposing some irregularities at the hospital.

Dr. Chandra, who went to the UK to practice as a doctor, met Wijeweera there. When Wijeweera proposed to marry Srimathi, Dr. Chandra had given his consent without asking anyone. Srimathi, who had dreams of exploring the UK as her younger brother prepared documents to get her there, was shocked to hear that her marriage was decided by his brother.

She had seen the JVP Leader once when he visited her home in Moratuwa to meet H.N. and had a glance at him without knowing he would be her husband soon.

“With a few of my friends I rushed to our living room just to see him as he was the Leader of the JVP,” Srimathi said, recalling her first encounter with Wijeweera, saying that she felt nothing particular about the ‘elderly bearded man’ who humbly greeted her with a smile.

“When I think of my brother Chandra today, I think he is the most selfish man in the world. He wanted to become important by making Rohana his brother-in-law. Chandra was not a member of the JVP but a sympathiser who supported the party financially. He gave his car to the party. He declared himself as Rohana’s personal doctor. I had to sacrifice my future and dreams to make him happy,” she claimed.

She mostly feared languishing in jail with him. “We had a hard time in 1971 with the JVP insurgency. Our relatives blamed our parents for not bringing up the two boys, who were in jail, properly. We didn’t have peace during that time and they cornered us again as the family had two ‘Che Guevara-karayos’ (rebels). I thought I didn’t want to marry the man who created that situation,” she said.

A new life

With no option to stop the forced marriage, she made up her mind to marry him. They got married and moved to Tangalle, Wijeweera’s hometown, to start a new life.

The JVP’s commemoration ceremony to remember those who died in the 1971 insurgency which was held island-wide in April 1980 was the first and last event for which Srimathi accompanied her husband. Since then she lived the life of a prisoner, only tasked with giving birth to children and raising them. The truth was she spent a life denying her rights as a woman. Most of the time she was voiceless.

Living in hiding for over five years, she ran with him and five small kids from place to place. Everything they owned was contained in a suitcase, which they carried when changing places of living in fear of being captured by the military or the Police.

H.N. was a Central Committee member of the JVP and his decision to break away the Sri Lanka Teachers’ Union from the JVP in mid-July 1980 upset the JVP. “Rohana told me that the Central Committee had asked him to divorce me as H.N. had betrayed the party. The Committee had questioned him saying that if H.N could do that to the party, how they could believe that his sister would not betray the party one day. But, I think since I was pregnant, Rohana didn’t listen to the Committee’s decision. The JVP started ill-treating me from the beginning,” she said in a quivering voice.

Srimathi, the woman who was rendered voiceless and cried over the party’s decision that Wijeweera should divorce her, gave birth to six children during her marriage to Wijeweera that lasted only for nine years.

“He wanted to have 12 children. I didn’t disagree as I felt I was voiceless. He loved children and would do anything for children. Rohana wanted to separate family life from politics. He never discussed politics with me,” she revealed.

Life of imprisonment

Even before the JVP was declared a proscribed political party in 1983, Srimathi had been ‘imprisoned’ in whichever house Wijeweera lived. Her only tasks revolved around the children. With no chance of attending weddings or parties and family gatherings, her life was spent caged in her room. She was prohibited from having any association with outsiders or relatives.

Close JVP female members who worked as domestic aides did the cooking, washing, cleaning and gardening while two trustworthy males were assigned for duties as a driver and a watcher.

“Soon after we got married, once I asked Rohana whether I could go for a relative’s wedding. He angrily said the JVPers were not attending weddings at hotels and asked me not to go. From that day, I never asked that question,” said Srimathi, who had stepped out of the house only to deliver the children and to get medicine and routine injections for them.

She was never accompanied by her husband on those visits but by the driver, a domestic aid and the watcher.

They lived in her ancestral house in Moratuwa until the Government banned the party in 1983, after the ’83 Black July riots. Wijeweera covered all open verandahs with hardboard and padlocked the gate, which was open to everyone when Srimathi’s father was there. Though he did that to have a good security cover as the JVP Leader, the neighbours this differently. They openly criticised him saying that although the JVPers were preaching about serving the masses, in reality they had distanced themselves from the ordinary people.

Srimathi was instructed to go into a room with the children when party members would come to discuss matters with Wijeweera. Gradually she got used to his style of command and would obey him without grumbling.

July 1983 riots

When the July 1983 communal riots erupted and as the situation escalated, Wijeweera decided to flee to Tangalle and instructed Srimathi to get ready with two children – Isha and Charga – and their baby items. They went to Tangalle through the flames of burning houses, vehicles and belongings of Tamils. Somawansa Amarasinghe who was with them in the vehicle got down in Kalutara.

Wijeweera dropped Srimathi and the two children at his house, gave some instructions to his brother and sister and vanished quickly. After that she didn’t see him for over five months.

Meanwhile, after the week-long riots, the J.R. Jayewardene Government banned left-wing political parties – the Communist Party, the JVP and the Nava Sama Samaja Party – although it didn’t have proper evidence to prove their involvement in causing the communal riots.

This made Wijeweera go underground while Police teams from Tangalle and Colombo stormed into Wijeweera’s house frequently and questioned Srimathi about Wijeweera’s whereabouts and some politically-related issues.

“When I said I was unaware of anything, they didn’t believe me. They told me normally wives knew everything about their husbands and they suspected me of lying. They didn’t believe me when I said that Rohana never discussed anything with me. I heard some officials saying I was a very cunning woman. Only I knew the truth,” said Srimathi, explaining her plight of being subjected to harsh questioning by Police officers, although they never physically harmed her.

After a few months of Wijeweera’s disappearance, CID officials, including female officers, took her and his brother to the 4th floor for questioning again. They asked the same questions but she gave the same answers during the hours-long interrogation, saying that she was unaware of his whereabouts.

Reunion and new identities

Wijeweera, who was in touch with his brother and sister, was worried about keeping the family in Beliatta and had asked his brother to bring them to Haputale. When the van was stopped at Haputale, a man with no beard and very short hair had got into the vehicle. Srimathi had identified him as Wijeweera only by his voice. It was a reunion after five months. He had been hiding in the forests in Tanamalwila.

Since that day, the Wijeweera couple turned into Attanayake Mudiyanselage Shantha Wimalasiri and Samarakoonarachchilage Priyani Chandima.

Shantha Wimalasiri, introducing himself as a planter, started life together with his family at an estate bungalow in Nuwara Eliya. They stayed there only for few months as Wijeweera kept on changing the hideouts. They went back to Tangalle and then again shifted to a tea estate in Rassagala, Balangoda. Then they moved to a house in Haldemulla, which was purchased for Wijeweera by the party and stayed there for three years. There, Srimathi gave birth to their third and fourth daughters.

The JVP’s Politburo members – Somawansa Amarasinghe, Upatissa Gamanayake and a few other trustworthy JVPers came to meet Wijeweera. During this time he accompanied them to hold the JVP’s monthly Politburo meeting and organising.

The Wijeweera family, which got friendly only with two families in the neighbourhood as the ‘Attanayake family,’ had suddenly vanished two days after Srimathi was questioned by the Police in connection with a robbery in one of the houses. The Police searched the ‘Attanayake’ house the next day and this alerted Wijeweera. Following the instructions of Gamanayake, Wijeweera ordered Srimathi to get ready to flee.

Their next hideout was Lewwegoda estate, which was next to Neluwe Estate, Bandarawela. The 13-acre estate with beautiful surroundings was owned by a planter named Reginald Patrick. Reginald, who was fondly called “Reggie maama” by Wijeweera’s children, was Somawansa Amarasinghe. He introduced Srimathi to the estate workers as his sister.

Half of the Katunariya Walawwa, the large bungalow in the Lewwegoda estate, was occupied by estate workers and the other half by the Attanayake family. Officers of the Bandarawela Police Station frequently came to the estate to buy anthurium flowers from the estate, which had a large anthurium cultivation. This made Wijeweera change the hideout again.

They stayed in several places, including Uppatissa Gamanayake’s house and in another strong JVP supporter’s house in Padukka until October 1988. Then the disguised family again started living in a small estate bungalow in Ulapone.

“The party supported us to get some furniture to suit the financial status of a planter. One small bar with luxury liquor bottles was installed to show that Attanayake was still a heavy boozer though he had suffered a minor paralysis due to drinking. Our two elder daughters started schooling at the village Primary School. A teacher from the Ulapone area came to the house to give them tuition as they had missed primary education since the family was on the run. We led a normal life in Ulapone and Reggie, Gamanayake and a few others continued to visit our house for discussions. Rohana used to go with them on week-long visits,” Srimathi said, recalling their final months together.

A loving father

She said that when Wijeweera was at home, he loved to read bedtime stories – fairy-tales and other Sri Lankan folk stories – to the children. He taught them English for two hours daily.

“He loved his children a lot. He always wanted his children to be around him. Our elder daughter was a little stubborn from her younger days and Rohana was tough when she was naughty,” Srimathi said.

Other than children’s story books, Ladybird English books and an encyclopaedia, Attanayake didn’t have any books in his house. He read two weekend papers and watched the news on TV in his spare time.

It was in early November that Attanayake started his routine monthly week-long trip with Gamanayake and Saman Piyasiri Fernando. According to Srimathi, they normally started the trip from Reggie’s estate after having discussions there.

Reggie’s friend, the Manager of the Neluwa Estate, called one of them to convey the bad message that the JVPers had stormed into the Lewwegoda estate and killed several workers. He confirmed that Reggie had not come to the estate that day. Though it was an attack by the Army, the Manager thought it was done by the JVPers. Instead of staying for a week, Wijeweera returned home with Gamanayake and Saman within two days.

“Standing near the gate, they discussed something for more than 45 minutes. From their voices, I felt they were having a serious discussion. It was also unusual for Rohana to be outside as normally he would directly come in the house to avoid anyone seeing him. Then he came to the garden and I was standing near the window that faced the garden. When the two JVP girls asked him whether there was a problem, he said, ‘We went to all the places but Reggie, who was supposed to be in those places, hadn’t come. He was not there in Neluwa too. This is very strange,’ Then Gamanayake and others requested Rohana not to stay at home that night. He agreed and came into our room to see the children. When he saw the children, he changed his mind. Asking the others to go, he said that he would stay with us that night and would come the next day,” said Srimathi, adding that she never thought it would be Wijeweera’s last night with his children.

He instructed the two girls to be vigilant at night. Though he was upset, he read bedtime stories with the children and fed them too.

Captured by the Army

The next afternoon, while he was reading a newspaper after lunch, the watcher opened the gate thinking Gamanayake and Saman were coming to pick up Wijeweera. Wijeweera, who suspected that someone else was arriving in that unknown van, hurriedly walked towards the back garden. The van raced through the winding gravel road that led to the estate garden and some uniformed men jumped out of the van and caught Wijeweera.

The Army officials – including Col. Janaka Perera, Capt. Gamini Hettiarachchi and Karunaratne – brought him into the house and asked him to wear spectacles to verify that ‘Attanayake’ was Rohana Wijeweera. He accepted that he was Wijeweera and requested them not to harm his wife and children, saying they were innocent.

For nearly half-an-hour like a mantra he pleaded them several times saying, “Please don’t harm my wife and children.”

He asked the officers whether they came from Kandy but they said they came from Colombo following the orders from then Army Commander General Hamilton Wanasinghe.

“I heard him saying that he was not ready to meet any top Army officials but wanted to meet a prominent political figure. He agreed to go with them wearing the sarong and a t-shirt which he was wearing at that moment but the officers asked me to give him an ironed shirt and a trouser,” Srimathi recalled.

Srimathi, their children and the two JVP girls kneeled down near him to say goodbye. Janaka Perera asked her not to break the news to anyone that Wijeweera was taken into custody. Wijeweera got into the van but before it passed the gate he had requested the team to be allowed to give an important message to Srimathi.

“Please educate my children well, but don’t change their religion,” were his last words to Srimathi on 12 November 1989.

Then he instructed one of the JVP girls to call Kalu Malli (Gamanayake) and hire a van to go Padukka, where they used to stay in a house belonging a strong JVPer. Srimathi told that she would go to her house in Moratuwa but Janaka Perera advised her not to go there, saying it was not safe for the family.

Rohana Wijeweera killed

The van raced through the estate. Srimathi, the five children and Wijeweera’s mother, who reached the Paddukka house the next day in the afternoon, watched the ‘breaking news’ saying that the JVP Leader Rohana Wijeweera had been shot dead.

His mother fainted and Srimathi cried. The two little girls – Isha and Charga – didn’t recognise the old picture of the bearded man shown on TV as Rohana Wijeweera but cried as their mother and grandmother were crying.

“Rohana never thought that he would be killed. He wanted a political intervention to lift the ban on the party. But the then Government didn’t keep him as there would be a huge outcry internationally to release him. I felt that something would happened to him that time and thought that was the last time I might see him,” said Srimathi, emotionally.

Srimathi says that she saw Rohana half-dead on TV, delivering his last message to the public and that he was badly tortured and assaulted.

“I wanted an investigation into my husband’s death. He was unarmed at the time he was captured. I later heard that he was burned alive. I lodged a complaint with the Police three months ago, but still no one has contacted me,” Srimathi charged.

Still weeping over the ruthless killing, she is yet to receive her husband’s death certificate. Later, she heard that Gamanayake and other close associates of Wijeweera were also killed except Reginald Patrick.

Family surrenders

With the Government urging Wijeweera’s family to surrender, the family in Padukka, which first treated them well, had started ill-treating them. Due to fear of being arrested for sheltering Wijeweera’s family, they urged Srimathi, who was three months pregnant, to move out from the house soon and stopped providing them food.

“I posted letters to the Sri Lanka Army and the Police saying that I wanted to surrender. I was clueless about what I should do next as Rohana had never discussed anything with me. After several years of living in hiding with him, I had doubts about what my future would be with five kids and an unborn child. A few months before his death I asked this question but Rohana got angry and scolded me for having negative thoughts. I think he was not ready to die and thought of coming back into mainstream politics. I was unaware that I could seek political asylum, so instead of reaching a diplomatic mission to seek asylum, I went to the Army Headquarters to surrender. Now I regret taking that wrong decision,” she said.

Becoming the decision maker for the first time in her life, Srimathi decided to surrender to the Army with her five children and Wijeweera’s mother. They met top military officials – Army Commander General Hamilton Wanasinghe, Maj. Gen. Cecil Waidyaratne who led the final operation against the JVP in 1989, Defence Secretary General Sepala Artigala, Brigadier Lucky Algama and President’s Secretary K.H.J. Wijedasa – at the Army Headquarters.

“President R. Premadasa spoke to me over the phone saying he couldn’t meet us as he was at a function outside Colombo and that Rohana died because he failed to listen to him. I don’t know what he meant by that. But he assured the safety of the family. The next afternoon we were taken to the Parliament to meet the President. In front of the then Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne, Army Commanders, Police Chief, K.H.J. Wijedasa and the Chief of the CID, he said that he gets thousands of calls requesting him to kill Wijeweera’s family saying that ‘snake’s babies will be snakes one day; destroy them all’. Isha and Charga, who could understand the word kill, ran behind me to hide. He said that Rohana had killed many of his supporters but he would give us protection,” Srimathi recalled, saying that her children now say it was better if the Government had killed them all that day to avoid being harassed for being Wijeweera’s children.

Today, 26 years after the killing of Wijeweera, Srimathi says she was a mismatch for the JVP’s Founder Leader, who was a serious person who did not speak or joke much. “He was very stern in his decision-making and didn’t allow me to express my views. If I expressed my opinion, he would get very angry. He wanted me to be an obedient wife and I suppressed my voice for the sake of keeping the marriage going,” Srimathi said, with a smile.

It was not easy or rosy to share her life with the revolutionary leader Wijeweera. It was this humble and charming yet determined woman’s sheer tolerance, obedience, dedication and love to have a closely-knit family that made her journey with Wijeweera worthwhile.

“I came to know about his vast knowledge in medicine, Russian politics and his revolutionary activities only through articles in the papers. He could speak five languages including French and Tamil. Though he was a revolutionary, for me he was the man who married me against my will and made me a prisoner for nine years. But I still respect him. I started my real struggle after he died as I had to raise six very small kids and make his last request a reality,” she said, adding that neither she nor any of her children wanted to enter into politics from the JVP which Wijeweera created, as it had ill-treated her family in many ways.

With no wealth left by Wijeweera, Srimathi, who has lived for over 26 years in military bases, has only one dream now – it is to have house of her own for her and her children, as they have nowhere to go.

“I thank President Maithripala Sirisena for extending our stay at the Welisara Navy base for another six months but after March next year, we still don’t have a place to go. I am optimistic that the President will look into our plight,” she added.