Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 17 November 2015 01:34 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Lloyd Fernando

What inspired this note is a very significant observation made by W.A. Wijewardena, in his ‘My View’ weekly column in the Daily FT last week, on the PM’s Economic Policy Statement (http://www.ft.lk/article/493645/Economic-Policy-Statement-of-Yahapalana-Government--Building-concrete-plans-for-implementation-out-of-the-skeleton-is-needed---Part-1).

While observing that it is a rather overdue statement, Wijewardena goes on to say the following: “The policy statement is a skeleton – a kind of a synopsis synthesising the vast policy framework which the Government is planning to implement. Hence, every word, every sentence in it has to be developed into a separate action plan if it is to be properly understood by those who are to implement it.”

Then he explains the reason for this approach. “On the side of the Government’s administrative machinery, such understanding is necessary to avoid contradictions and inconsistencies that may creep in and cripple its implementation.” I may add that such an understanding is required not only at the administrative level but also among the ministers, who are expected to guide and instruct the administrators.

The ‘separate action plan’ Wijewardena recommends must be coordinated, taking into account the symbiotic relations that exist among various sectors and sub-sectors of the economy, as well as with the socio-political outcomes. Thus, for instance, while all the agricultural development projects have a final outcome in terms of sectoral outputs and impacts, they also have a relationship to the other sectors of the economy such as industry, trade, infrastructure and environment, to name a few. They also have an impact on the income of households and through that on the levels of consumption.

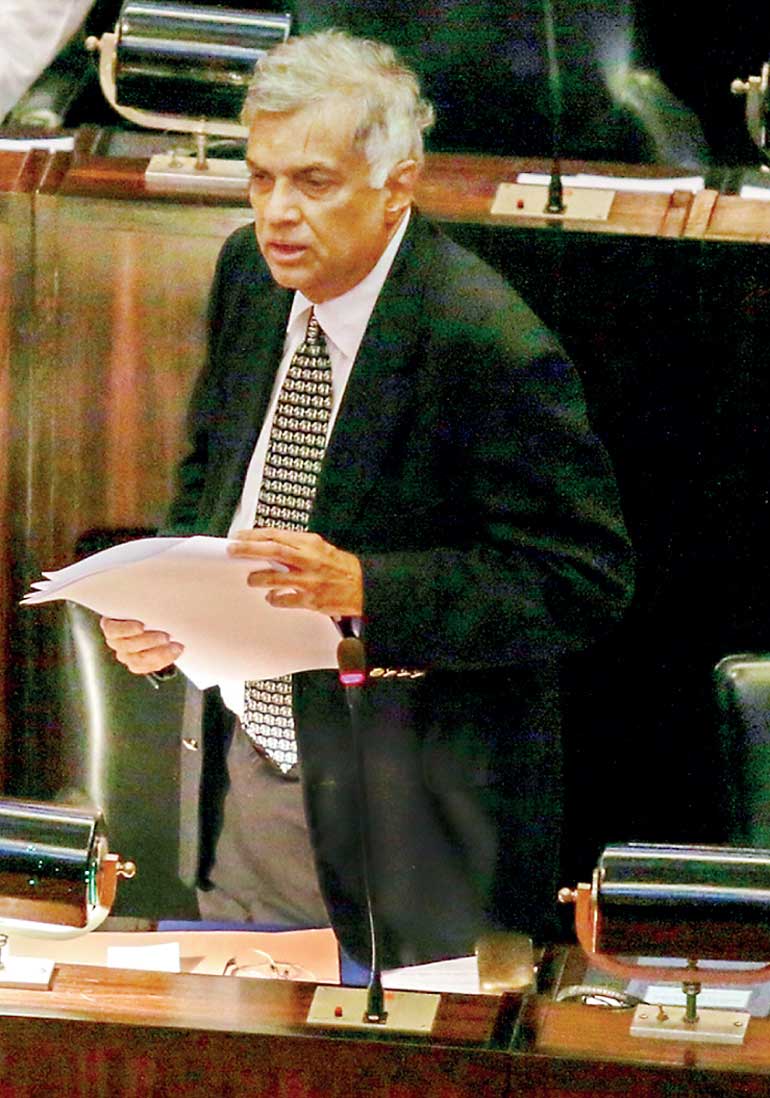

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe delivering his economic policy statement in Parliament

Intra-sectoral and inter-sectoral impacts

It is impossible to list out all the ramifications of intra-sectoral and inter-sectoral impacts in a short note. It is however quite possible that there are no imponderables in this regard even among non-economists.

These ramifications, symbiotic links and widespread impacts are captured when we approach development policy formulation and implementation using the well-known methodology that is popularly known as the system of “Management for Development Results” (MfDR). This approach is reinforced by the equally well-known methods of project appraisal, design and implementation. It helps to identify very clearly what we want to achieve in the form of Key Performance Indicators and test them with the opportunities for and constraints to achievement.

The Sri Lankan bureaucracy has been exposed to these concepts, progressively over the years since the early 1970s. What is required is the political will and discipline to formulate and adhere to plans of action using these methods.

1982-1993 period

The writer’s personal experience is confined mostly to the 1982-1993 period, when, as the head of the national planning apparatus he enjoyed support at the highest level coming from Presidents Jayewardene and Premadasa to enforce the necessary discipline in implementing government policy. Initially, it was Ronnie De Mel who helped the process and later, Paskeralingam acted as the intermediary with President Premadasa.

Government development policy was embodied in the medium term Public Investment Programme (PIP), which was prepared annually by the National Planning Department on a ‘rolling plan’ basis. The PIP which was prepared with the assistance of all ministries and departments became an instrument of discipline; no government entity was allowed to deviate from it without Cabinet approval.

The National Planning Department benefited a great deal in this regard from the role of the Committee of Development Secretaries, which was first chaired by Cabinet Secretary G.V.P. Samarasinghe (a confidant of President Jayewardene) and later after his demise by the Secretary to the Treasury. The National Planning Department served as the secretariat of the Committee of Development Secretaries and played a key coordinating and steering role by not only preparing the minutes and follow-up action but also by determining the Agenda for each meeting.

These meetings were held every week on a Tuesday, while the Cabinet meetings were held on Wednesday. There was a solid link between the two institutions, with the cabinet very often referring various memoranda to the committee of Development Secretaries for observation.

Upgrading the knowledge base

There were however, two major concerns for the National Planning Department which fortunately was adorned with top class officers with PhDs and Masters’ Degrees from the best universities in the world. They also benefitted greatly from the continuous intervention and dialogue with international think tanks such as the World Bank, the IMF and UN agencies. There was also a special unit in the department which had the responsibility for upgrading professional capacity of the staff on a continuing basis. Special projects supported by the Bradford University and the UNDP helped this process very significantly by supporting country based programmes. There was also a scheme to send officers to reputed international universities for postgraduate training, including at the PhD level.

The daunting task, however, was to upgrade the knowledge base at the ministries and departments that had to interact competently with the National Planning Department. This is what prompted the department to take the initiative in establishing the Administrative Reforms Committee (ARC) headed by the late Shelton Wanasinghe.

Convincing President Jayewardene about the urgent need to establish the ARC was a difficult task. It was Ronnie De Mel who was able to finally convince the President, who still did not see the need for a Commission and agreed to appoint a Committee.

Baku Mahadeva who was nominated as chairman walked into my room, which was next to his at the Treasury, furious that I had made the suggestion. His point was that he was not willing to spend his time and effort on a committee that will finally produce a report which will end up in the wastepaper basket. After much persuasion, however, he agreed to serve on the committee, which he suggested should be chaired by Shelton Wanasinghe, who was retiring from the ESCAP Secretariat in Bangkok. The other members were drawn from the Government, Academia and the Private Sector.

Mahadeva made a significant contribution as a member. Unfortunately his words of prophecy turned out to be true even though the 10 volumes produced by the ARC since December 1986 did not end up in the wastepaper basket. They have ended up in the libraries of both local and international academic institutes. Attempts made by successive governments, since the ten volumes were produced, have failed to implement the recommendations which are still valid, mainly because they were ad hoc and piecemeal efforts, which the Wanasinghe Committee in fact warned could be “not only counterproductive but even dangerous”.

Lack of sufficient dialogue with private sector

Another deficit the National Planning Department observed was the lack of sufficient dialogue with the Private sector. After all, the private sector, particularly after the 1977 reforms, was expected to play the role of the engine of growth. The Government, in order to assist the private sector had to understand its concerns and respond with effective measures.

Consultation with the private sector was, however, facilitated to some extent by the regular meetings held by Ronnie De Mel to which some of the captains of industry were invited. This included apart from C.P. De Silva, the late Lal Jayasundera and Reggie Candappa, the Exporters Forum held by Lalith Athulathmudali to which the Director National Planning was invited also proved to be very effective. Later during Premadasa’s era Ranil Wickremesinghe held regular Saturday meetings, which the writer was privileged to attend.

Need of the hour

Times have changed and it is not necessary, nor possible, to have the same system for inter-ministerial dialog and communication with the private sector. The need remains, however for a full-fledged National Planning Council (NPC) or a development advisory body to be established. Perhaps, the Prime Minister’s proposal to establish an Agency for Development could play that role.

To be effective, the composition of the agency, as well as the consultative process with the private sector by policy makers is very important. The NPC should have only members drawn from the professional community – apart from ex officio members, there should be representatives of the private sector, academia and civil society organisations. Regular reports should be submitted by the NPC to a Cabinet sub-Committee on Economic Development which will finally send up situation analyses and policy proposals to Cabinet.

The National Planning Council (or agency for development) will have no effective impact unless it is supported by a competent well motivated public service, at all levels. Ensuring this will be the responsibility of a competent Administrative Reforms Council. It need not reinvent the wheel. It could draw from the recommendations of the Wanasinghe Committee that have been studied at length and updated by subsequent committees and councils, which have also taken into account the experience of countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, Korea and New Zealand, where economic reforms were accompanied by public service reforms.

(The writer was concurrently Director General National Planning and State Secretary Ministry of Policy Planning before he joined the Board of Directors of the Asian Development Bank, Manila, in the mid-nineties. He is currently engaged in conducting the MPA and other public service capacity building programs at the Postgraduate Institute of Management.)