Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 7 September 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The people: A rally outside Parliament in Athens in June called for the Greek Government to agree a deal with its creditors – Reuters/Yannis Behrakis

Pivotal figure: Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel wanted the IMF involved in the Greek bailout, worrying that European Union institutions were not up to the task. Merkel is seen here in 2010 with former European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet (far left), former Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou (centre) and former French President Nicolas Sarkozy (far right) – Reuters/Thierry Roge

Leaning in: Former French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde, who now heads the International Monetary Fund, and Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who ran the fund until 2011. Pictured here in Paris in 2010, they both led the fund through uncharted waters – Reuters/Benoit Tessier

WASHINGTON/ATHENS (Reuters): Many of the top brass of the International Monetary Fund always had concerns about the plans  to bail out Greece. That much was clear as far back as 9 May 2010, when the IMF’s 24 directors gathered in Washington to sign off on the fund’s participation in the first, 110-billion-euro ($125 billion) rescue alongside European institutions.

to bail out Greece. That much was clear as far back as 9 May 2010, when the IMF’s 24 directors gathered in Washington to sign off on the fund’s participation in the first, 110-billion-euro ($125 billion) rescue alongside European institutions.

A Reuters examination of previously unreported IMF board minutes shows that a near majority of directors round the board table that day thought the Greek program would not work.

“We have serious doubts about the approach,” said Brazil’s then director Paulo Nogueira Batista. He slammed IMF forecasts for Greece as overly optimistic - “Panglossian.” Arvind Virmani, the Director from India at the time, said the program imposed “a mammoth burden” that Greece’s economy “could hardly bear.”

But they and others who feared the IMF was walking into a quagmire had little room for maneuver. The fund’s powerful Managing Director, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, and a handful of his advisers, feared Greece posed a threat to the wider euro zone financial system. They had already decided to plunge into the crisis. The doubters were given a blunt retort, according to the minutes.

“Let me be clear on a couple of things,” said then Deputy Managing Director John Lipsky, who chaired the board meeting. “There is no Plan B. There is Plan A, and a determination to make Plan A succeed. And this is it.”

Five years later, after the biggest bailout in the fund’s history, Greece failed to make a $1.7 billion payment as required at the end of June – the first advanced economy ever to default on the IMF. Worse, after having received more than 240 billion euros in international aid, Greece’s economy is still in tatters. Europe agreed a further bailout of 86 billion euros this month.

Fresh interviews with more than 20 senior officials, as well as an extensive review of IMF board records, illuminate the turmoil and divisions within the fund, then and now. They show Strauss-Kahn and his top advisers set the fund, which by tradition has always been led by a European, on a course known to be flawed, and that non-European shareholders doubted would work.

To drive through the Greek bailout, the fund bent its own rules. It lifted an IMF ban on the fund lending money to countries – like Greece - that were unable to pay their debts. It also allowed European politicians to dictate initial terms in the Greek rescue, ruling out a debt restructuring that could have given Greece a fresh start. And it shaped economic forecasts to fit political ends.

The fallout still weighs on the fund. The IMF now says it will not participate in the latest Greek bailout unless Europe allows debt restructuring on a scale Europe has so far rejected.

Strauss-Kahn, who quit the fund in 2011, would not be interviewed for this article. But supporters of the fund’s actions say he and the fund had little choice other than to help in the Greek crisis. The fund went against its previous policy, they say, to prevent the Greek crisis causing wider financial chaos.

“With Europe hanging in the balance ... to say the fund would not be involved ... would not have been acceptable,” said Siddharth Tiwari, who was Secretary of the IMF Executive Board in 2010 and is now the Head of the fund’s Strategy, Policy and Review Department. The Greek bailout did indeed stop “contagion” in financial markets. European banks escaped potentially disastrous losses, and other deeply indebted European countries stuck with their programs of economic reform.

But Greece has paid a heavy price. One senior IMF economist, while agreeing the fund had to intervene, said of the bailout: “Objectively we made Greece worse off ... You’re lending to a country that is already unable to pay its debt, and that is not our mandate.”

European opposition

One reason the IMF’s participation was troubled was because initially Europe wanted to keep the fund at a distance.

Created as a global lender of last resort to help European countries after World War Two, the IMF rapidly moved to helping developing nations around the globe. Its typical “customers” are small, emerging economies needing loans as they implement structural changes.

Greece was different: Though small within Europe’s economy, it was an advanced country that shared the euro currency. It was initially unthinkable to European leaders that such a country should require rescue by the IMF.

Instead, the Europeans wanted to keep the Greek problem in-house. Paris, in particular, opposed bringing in the fund. George Papaconstantinou, Greece’s Finance Minister from 2009 to 2011, remembers French President Nikolas Sarkozy “telling us ‘I will never allow the IMF in Europe.’”

Christine Lagarde, then France’s Finance Minister and now Head of the IMF, agreed with Sarkozy. Her view, she told Reuters in an interview, was “predicated on the hope that the Europeans could put together enough of a package, enough ring-fencing, enough of a backstop so as to show that Europe could sort out its own affairs.”

In Frankfurt, Jean-Claude Trichet, then President of the European Central Bank (ECB), also made clear he wanted Europe to take the lead. “I wasn’t hostile in principle to an IMF intervention,” Trichet told Reuters. “But I was resolutely, totally and very publicly hostile to the idea that the IMF should go there alone, which was a thesis that seemed to prevail at some point.”

The debate and delay over deploying the IMF would prove damaging. “In the history books they will look back and say that was a valuable learning experience,” said a former senior IMF official of Europe’s early efforts to go it alone. “From another point of view, everybody fiddled while Rome burned.”

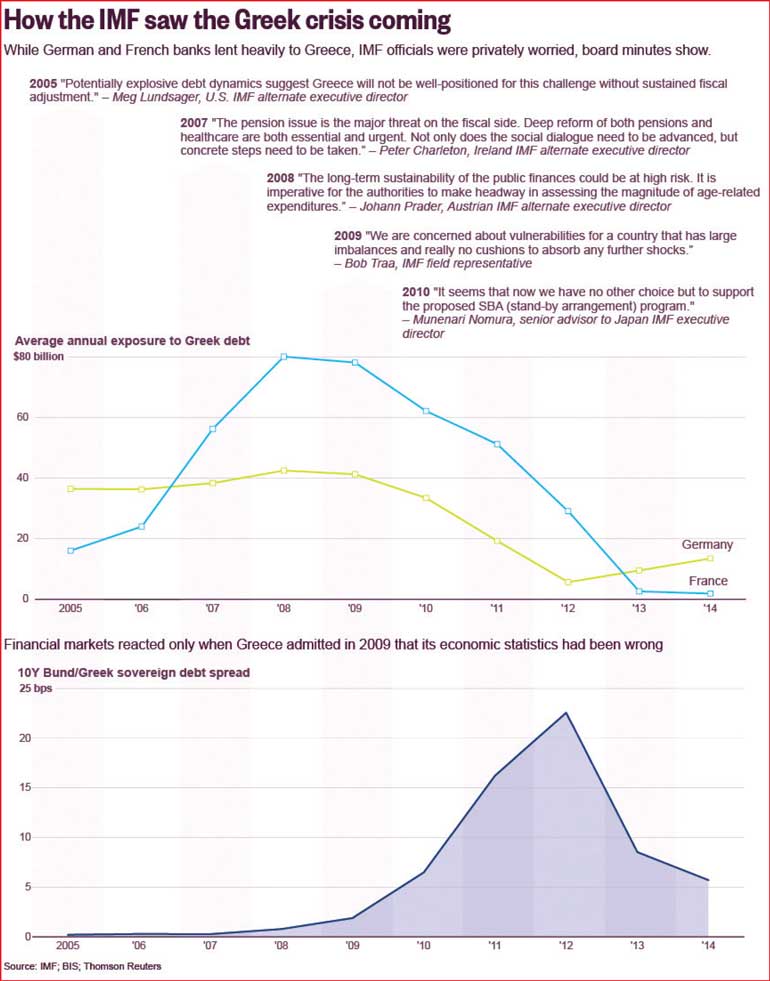

It soon became clear that Europe’s initial efforts had failed to calm the fears in financial markets that Greece might default. In early 2010 the Greek government’s cost of borrowing soared, a crisis of confidence that threatened to infect the debt of other European nations.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, according to her aides, saw the ECB and the European Commission – the EU’s top executive body – as soft and vulnerable to political influence. She began insisting that the IMF be brought into the Greek bailout.

The IMF had long experience running reform programs, and hundreds of experts to help. The Commission did not. “The IMF was brought in because of one very simple reason,” Papaconstantinou said. “(Merkel) came to the conclusion that the (European) Commission was not credible and that the only thing that could convince the markets would be the IMF.”

But there were obvious difficulties. Greece had no local currency to devalue to help exports and tourism, and no local central bank to shape monetary policy for the country’s particular interests. Those were the sort of levers the IMF would usually pull.

The IMF also had a rule stipulating that it could only lend to a country if there was a “high probability” that its overall debt load was sustainable – essentially, that the nation was solvent. No one at the IMF felt comfortable making that statement about Greece: The country’s budget deficits and skyrocketing debts seemed to point to eventual default.

So Strauss-Kahn and his staff rewrote the rules. Under the new formulation, countries judged to be of “systemic” importance – Greece, as part of the euro zone, was deemed to meet the definition – could still get IMF help.

“Tactical error”

Strauss-Kahn drove the IMF down a route it had never taken before: operating as part of a “troika” with the European Commission and the ECB. It was a serious constraint for an agency used to dealing directly and alone with creditor governments. While Europe had accepted IMF involvement, it still wanted to maintain control of the Greek bailout on its own terms.

Some IMF officials were worried about who would lead negotiations with the Greeks. James Boughton, a former IMF economist who was also the fund’s in-house historian, remembers feeling that Europe didn’t seem to care what happened to the Greek economy as long as the euro zone’s financial system was protected.

The IMF should have pushed back more, said Boughton, who is now a senior fellow at the Center for International Governance Innovation in Canada. “DSK (Strauss-Kahn) made a tactical error in letting the fund get trapped in this troika arrangement,” because it locked the three organisations into speaking with one voice and did not allow the IMF enough independence.

The greatest angst was over the issue of debt restructuring – or lack of it, some IMF officials recall. “It was absolutely clear in the (IMF) building – not to everybody, but to the vast majority of us – that there was a need for debt restructuring,” the senior IMF economist said.

In plain English, “restructuring” means that creditors forgive borrowers part of their debts, cutting deals to accept less than they are owed. But the Europeans opposed restructuring. They feared European banks loaded with Greek bonds could collapse, and argued restructuring would spread Greece’s financial woes to other parts of the euro zone, spurring other countries to ask for their own debt deals.

So when the IMF developed its detailed program on Greece, it included no debt restructuring. The initial plan assumed Greece would repay every euro it had borrowed - not because the IMF thought it could or would, but because the Europeans refused to countenance anything else.

“The authorities upfront ruled out that option and no alternative options were discussed and developed,” said Poul Thomsen, head of the IMF’s Greek program, in his presentation at the board meeting of 9 May 2010, according to minutes of the session. “Fundamentally, our assumption is that we can put Greece ... on a credible fiscal path.”

Despite the grumblings of some board members, the IMF agreed that debt restructuring would have to wait. But the initial Greek program went off track, just as sceptical board members had feared. The economy tanked and the Greek government failed to deliver fully on reforms, such as privatising state assets and opening up markets.

According to former Greek Finance Minister Papaconstantinou, Strauss-Kahn finally decided to get tough with Merkel and insist on debt restructuring in May 2011. Then the unexpected intervened: As Strauss-Kahn was on his way to Europe to meet the German chancellor, he was arrested in New York after a hotel maid alleged he had sexually assaulted her. Under intense media scrutiny, Strauss-Kahn quit. (In 2011 New York prosecutors dropped charges against him and he reached a settlement with the maid.)

The debt meeting never happened. Some involved in the talks think the missed chance, as well as turmoil within the IMF following Strauss-Kahn’s departure, caused a fateful delay in the attempt to get Europe to embrace debt relief. “I am not saying that Merkel would have been convinced,” Papaconstantinou said of the cancelled meeting. “But the discussion could have started much sooner.”

Acts of cruelty?

In the eyes of Greek officials, senior figures at the IMF and in the troika did not understand the limitations of the Greek economy. As Greece repeatedly fell short of economic targets, troika officials in Athens tried to explain the realities to their bosses, according to both Greek and troika officials. Greece’s fractured politics, voters’ opposition to austerity and the vested interests of wealthy oligarchs made swift reform difficult, they said. The message did not get through.

A senior IMF official who used to run policy told Reuters: “We were not fully aware that these guys (the Greeks) did not have the system, the controls, the bureaucracy to deliver.”

Evangelos Venizelos, who took over as Greece’s Finance Minister in the summer of 2011, said the problem was political. “They (the IMF and Europe) insisted on measures that were acts of cruelty to make us prove to them that we were prepared to pay the political cost,” he told Reuters. Such measures included abrupt redundancies in the state sector and reducing private sector salaries - though the Greek government resisted the latter.

Eventually Greece did get some easing of its debt burden when private investors accepted a “haircut” of more than 50 percent on about 200 billion euros of Greek bonds they held. At the same time Greece borrowed 130 billion euros more from European state institutions in a second bailout. The IMF remained doubtful the program would pull Greece out of the mire. When the haircut and new bailout were finalised in February 2012, Lagarde, who had taken over as head of the fund, voiced her concerns. Gikas Hardouvelis, economic adviser to then Greek Prime Minister Lucas Papademos recalled: “All the ministers were congratulating themselves and Christine Lagarde stood up and said something like: ‘Guys, don’t congratulate yourselves – because in three years you’re going be called to give more money.’ She didn’t believe that this was a final deal.”

Tougher stance

Lagarde proved to be right. At the end of June Greece missed a payment to the IMF and then scrabbled to secure another rescue.

Most in the IMF believe one of the reasons the troika program failed was because a succession of Greek governments never implemented reforms properly. Greek critics, on the other hand, say the IMF made mistakes, such as trying to drive down workers’ wages instead of putting more emphasis on liberalising markets.

The fund has acknowledged it misjudged some basic economic forecasts – particularly how deep government budget cuts would inflict significant harm, at least in the short-term, on a country that depended heavily on state spending. According to the European Commission, government spending accounted for 49% of Greece’s economic output in 2014.

The IMF still has to decide whether to join a third bailout for Greece, agreed by European institutions this month. It is widely expected to do so, but not before receiving a commitment from Europe that Greece will be given some form of relief on its towering debts. Since most of the debt is owed to euro zone governments, it could take months before Europe decides how to proceed.

Wider questions are also pressing. Two IMF officials told Reuters that a growing number of staff are pushing to scrap the policy change that Strauss-Kahn enacted to allow the IMF to intervene in Greece. However, the United States, the IMF’s largest shareholder, believes the “exceptional access” rule should remain.

The IMF’s involvement in the euro zone has also intensified debate over the dominance of the institution by the United States and Europe. Lagarde is expected to win a second term as managing director if she seeks one; but China, India, Brazil and other shareholders beyond the West want a greater say in the organisation. If the IMF can get itself overexposed in its own backyard of Europe, they argue, something has to change.

Lagarde appears determined not to repeat the fund’s earlier approach. In a statement released on Aug. 14 as euro zone ministers debated the third Greek bailout, the IMF head said it was “critical for medium and long-term debt sustainability that Greece’s European partners make concrete commitments ... to provide significant debt relief.”

Last month, Reuters reported that a new IMF analysis found Greece still needed debt relief beyond anything Europe had so far considered.

It was no accident that the report surfaced: The failure of the previous Greek bailouts had triggered an intense round of soul-searching inside the IMF and a reappraisal of its approach. Fund officials floated the report in the midst of crucial negotiations to make their view on debt restructuring public, even though it was at odds with their troika partners.

Boughton, the former IMF economist and historian, said: “Now the fund, five years after the fact, is publicly saying that you cannot solve this problem without a major debt restructuring. It’s great they’re saying that now, but they should have said it in 2010.”