Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 4 August 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Marwaan Macan-Markar

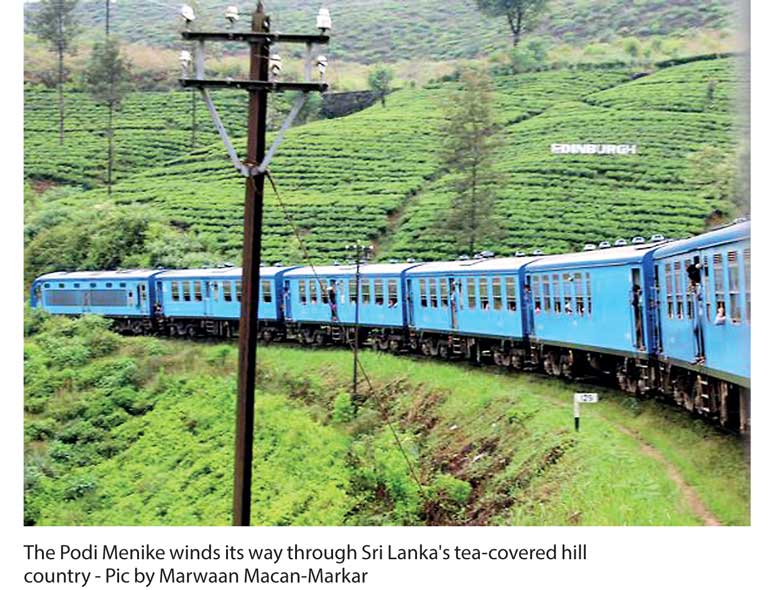

Nikkei Asian Review: Just as the Sri Lankan capital stirs, the Podi Menike, or Little Maiden, creaks and groans as it pulls out of Colombo Fort Station. The train is bound for Badulla, 290km away at the southeastern edge of the island’s hill country. The 5:55 Menike was part of my life in the early 1990s, when I lived for two years in Nuwara Eliya, a chilly, mist-draped town 1,868 meters up in the mountains.

I recently boarded the Menike for the 10-hour ride to visit Ella, a stop near Badulla. I was heading there to report on the recent interest that globe-trotting millennials had taken in the town. They are drawn to the place for the treks through its tea-covered slopes; the train also features heavily in their social media posts.

The Menike’s first stretch out of Colombo is through a tropical tangle of low land urban and rural life. The journey serves up ample scenes of a habit embraced during British colonial rule.

Sun-drenched Sri Lankan streets are dotted with tea shops, often crowded during the breakfast hours and when people take a midmorning break for a cup of tea. Add to this a break for afternoon tea at around 3 p.m., and the national rhythm of tea-drinking life on the South Asian island is almost complete.

But there is more to this very British legacy. This year marks the 150th anniversary of the first crop grown commercially on a small tea estate near the old royal city of Kandy, up in the hills. And the Sri Lankan government and industry leaders have brewed a special celebration – a “Global Ceylon Tea Party.” From January through August, the best teas from Ceylon, as the country was formerly called, are being served up at the country’s diplomatic missions across the world.

Sri Lanka is currently the world’s fourth largest exporter of tea, but the anniversary celebration is also an occasion for reflection that goes beyond simply celebrating the commodity that put the island on the world map. Ultranationalists among the majority Sinhalese have made sniping at the British Raj something of a national pastime. Even tea has been thrown into the pot. They attack the land policies imposed by the colonial rulers to command tracts of the hill country for tea cultivation. How much longer will they remain bitter?

Fortunately, a journey on the Menike through the heart of tea country provides a window on the progress made by another group of Sri Lankans. They have built on the pioneering efforts of James Taylor, the young Scottish planter who first experimented with a commercial tea crop on his Kandy estate in 1867. They are behind the spread of the evenly pruned tea trees that cover sweeping stretches of mountain slopes shimmering in the sunlight. Smallholder tea farmers today account for 65% of the 320 million kg of black tea produced every year in Sri Lanka – meaning they alone produce far more than what the British-dominated plantation companies could manage when the island gained independence in 1948.

Yet they are not the only ones who have made a virtue of the Raj’s success at controlling nature and imposing rules to convert mist-covered mountains, some above 2,000 meters, into productive land. Even the Menike – a feat of British engineering – is part of this legacy. The first train chugged up to Kandy in the year of Taylor’s commercial tea triumph. And as the Raj spread tea plantations across the rugged and chilly hills, the train tracks followed to carry the commodity to Colombo Port.

The journey today still offers scenes tailor-made for a period film of life during the British Raj. As the Menike winds its way along steep mountainsides, it stops at small stations that look like English country cottages. In some, the white-uniformed stationmaster still manually operates instruments to ensure the trains run on time, embracing to the last toot this British legacy.

As the Menike reached Ella, I had an image of the ultranationalists still grumbling about the Raj as they sipped steaming cups of sweetened, milk tea. Living in denial is a luxury for some, I suppose.

(Marwaan Macan-Markar is an Asia regional correspondent for the Nikkei Asian Review.)