Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Tuesday, 18 July 2017 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ganeshan Wignaraja

By Ganeshan Wignaraja

Trade in Sri Lanka – a classic small open economy in the Indian Ocean – is under scrutiny in difficult economic times. The country faces a myriad of issues. A persistent balance of trade deficit is straining scarce foreign exchange reserves.

Exports are concentrated in tea and clothing. Large firms dominate export activities. Sri Lanka is also confronting an uncertain external economic environment. World trade has slowed since the global financial crisis and protectionism is rising. The US has adopted an America First approach and left the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Brexit has prompted a re-think of EU and UK trade.

China, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, and others in East Asia witnessed rapid expansion of manufactured exports over several decades and are continuing to deepen their process of industrialisation. The recent formation of a concentrated supply chain hub in East Asia – popularly known as ‘Factory Asia’ – has attracted considerable interest. The East Asian economic precedent of coherent business strategies and supportive national policies shows how Sri Lanka could stride ahead in emulating Factory Asia.

The rise of factory Asia

Global supply chains refer to the geographical location of the various stages of production (design, production, marketing, and service activities) in a cost-effective manner and linked by trade in intermediate inputs and final goods. A large multinational company typically manages many suppliers, funnels their work into a single product and distributes it to its customers at a reliable speed.

For example, Apple – one of the world’s most iconic companies – has a technologically complex and geographically dispersed global supply chain. The Apple iPhone is designed by Apple in the US and largely assembled in China by Foxconn and Pegatron but individual parts are made by more than 200 suppliers located internationally.

Hence the displays of iPhones are mainly made in Japan by Japan Display and Sharp and some are made in South Korea by LG Display; whilst the screen and Gorilla Glass for the display is made in the United States by Corning. The DRAMs and Touch ID sensors are made in Taiwan by TMSC. The batteries are made in South Korea by Samsung and in China by Huizhou Desay Battery.

The accelerometers are made in Germany by Bosch. Apple coordinates the iPhone supply chain and does the design, development, marketing and creation of software in-house. Simpler supply chains exist in a wide range of manufacturing activities such as clothing, food processing, machinery, electronics, and automotives.

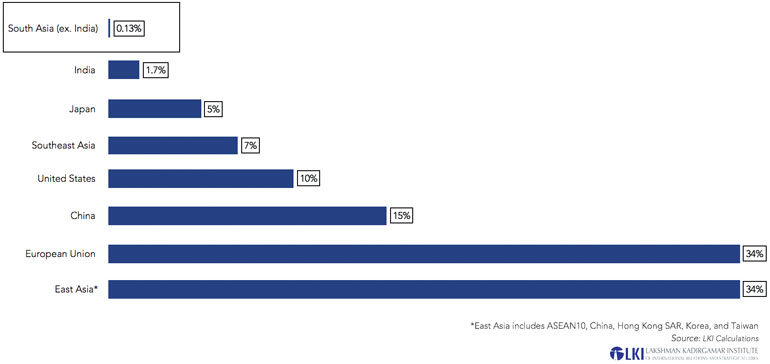

East Asia’s shift from a poor, less developed agricultural periphery to a wealthy global factory over the last half a century is an economic miracle. The extent of the region’s participation in global supply chains is significantly greater than elsewhere, and has spurred East Asia’s global rise to the coveted “Factory Asia” league with middle-income status for many economies. In 2015, the developing economies in East Asia accounted for 34% of global supply chain trade with China making up 15% and Southeast Asia for 7%. This compares with 34% for the EU, 10% for the US and 5% for Japan.

Sri Lanka’s opportunity

However, South Asia is a relatively small player. India accounts for less than 2% of global supply chain trade and the rest of South Asia, including Sri Lanka, for 0.13%. Slower growth and rising wages in China has encouraged an outward shift of labour-intensive segments of supply chains, ranging from clothing to electronics.

As trade follows geography, Southeast Asian economies (like Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam) and India are benefitting from supply chain spillovers from China. Sri Lanka may also benefit by attracting some labour-intensive activities from China, supplying services to its middle-class consumers (including tourism, information technology services and professional services) and increasing exports of tea and other primary products.

Sri Lanka is probably South Asia’s most open economy (with average import tariffs of under 10%) providing reasonable price signals for firms to join supply-chain trade. Close proximity to the huge Indian market, which is a magnet for Chinese outward investment, is another advantage.

Chinese affiliates located in India could subcontract production activities and services to firms in Sri Lanka, thereby promoting exports and jobs. Low wages, decent labour productivity and a dynamic clothing export sector are other locational advantages. Furthermore, Sri Lanka is on the map of the Belt and Road Initiative and has begun to attract significant Chinese investments in physical infrastructure.

Smart business strategies

Smart business strategies and market-friendly national policies have fostered the concentrated supply chain hub in East Asia. Being a big firm naturally creates advantages to participating in supply chains due to a larger scale of production, better access to technology from abroad, and the ability to spend more on marketing.

It is crucial for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) to work with large firms. Hence, smart business strategies, such as mergers, acquisitions, and forming business alliances with multinationals or large local business houses are all rational approaches; as is investing in domestic technological capabilities to achieve global standards of price, quality, and delivery.

East Asia’s experience suggests that nimble SMEs can also join supply chains by locating similar industrial activities in a defined geographic area and sharing access to local markets, technologies and skilled workers. Business associations can facilitate clustering of SMEs by facilitating co-financing a training centre, hiring a technical consultant to upgrade production technologies and mediating in disputes among SMEs. For instance, major industrial clusters are visible in Vietnam near Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, where large firms are surrounded by thousands of SME suppliers and subcontractors make garments, agricultural machinery, and electronics goods.

Market-oriented policies and FTAs

A focus on the supply-side of economic activity is at the centre of national policies in East Asia. Investing in education is a tenet, to create a base of skilled and productive labour for firms to participate in supply chains.

Modern cost-competitive infrastructure is also important to reduce trade costs for supply chains. This means investing in world-class ports, roads to ports, logistics, electricity supply, and information technology infrastructure.

Sound financial systems, which emphasise competition and collaboration among financial institutions to provide supply chain finance (e.g. anchor-spoke financing programs and credit bureaus for SMEs), and high-quality, affordable technical and marketing support services help SMEs to enter supply chains.

These supply-side measures best succeed in an open, market-oriented regime which transmits price signals to business and encourages domestic and foreign firms to invest. This means relatively low import tariffs, a competitive real exchange rate, and streamlined procedures for business start-ups and operations.

More controversial is the use of industrial policies in East Asia to target credit, subsidies, and public procurement schemes to particular sectors or firms. East Asia is replete with success and failure in the application of industrial policies. Some oft-cited examples of failures include Korea’s heavy and chemical industry push, Malaysia’s national car project (the Proton) and China’s home-grown 3G mobile technology TD-SCDMA. More research is needed on good practices, as there is a high risk of government failure and cronyism associated with industrial policies.

More recently, East Asian economies (particularly, South Korea, Singapore and Japan) have pro-actively negotiated free trade agreements (FTAs) with Asian and non-Asian economies. South Korea is considered the “rock star” in East Asia for having achieved the near impossible task of concluding comprehensive FTAs with both the US and the EU.

Concerns exist that FTAs have led to an Asian ‘Noodle Bowl’ of overlapping tariffs and rules of origin which are harmful to business. On balance, however, East Asian FTAs do provide net benefits to firms including preferential market access for supply chain trade, and easier trade facilitation. They have also laid the foundations for more open services markets and improving the coherence of regulatory frameworks. East Asia’s experience suggests that FTAs best operate when they are grounded in (or locked into) programmes of domestic structural reforms in the states that are party to the FTA.

Conclusion

Participating in supply chains provides another engine of trade-led growth in Sri Lanka in difficult economic times. It will help to increase exports, jobs, and incomes, among other macroeconomic benefits. Sri Lanka’s strategic geographical location in the Indian Ocean and its productive low-cost labour are advantages for supply chain participation. While there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach for Sri Lankan firms to join supply chains, East Asia provides interesting insights.

Smart business strategies, facilitating business associations, market-friendly policies and FTAs are all key ingredients, while business and government collaboration is essential to tailor these ingredients to national circumstances. By doing the right things now, Sri Lanka can emulate the success of Factory Asia and prosper.

Ganeshan Wignaraja is the Chair of the Global Economy Programme at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own. They are not the institutional views of the LKI and do not necessarily represent or reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.