Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 9 June 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

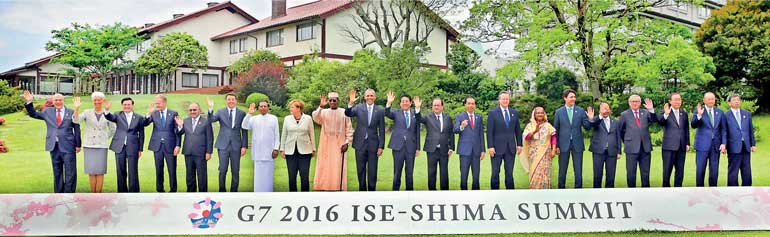

The G7 members and outreach partners pose for a family photo in Ise-Shima, Nagoya, Japan

The G7 members and outreach partners pose for a family photo in Ise-Shima, Nagoya, Japan

By Kithmina Hewage

President Maithripala Sirisena recently concluded a visit to the annual G7 (Group of Seven) Summit held in Japan. The G-7 consists of the seven most advanced economies in the world, as identified by the IMF, and represents more than 64% of the world’s net global wealth.

Therefore, the question most have been asking is, “what is the leader of a small island nation in the Indian Ocean with an economy worth just $80.5 billion doing at the G7 Summit?” Below I attempt to provide some context and shed light on the matter. I should note, however, that this is purely conjecture. This commentary is not based on any investigative journalism or access to sources, but simply trying to “connect the dots”.

Why was the President invited?

Two key elements appear to have resulted in the extension of the invitation to President Sirisena: geo-political considerations within the G7 and Sri Lanka’s own foreign policy.

Sri Lanka’s foreign policy reset

The country’s significant shift towards an alliance with China under President Mahinda Rajapaksa is well documented. While considerable discussion on the impact of this shift on Sri Lanka’s relationship with India and the West has taken place, the impact of Japan-Sri Lanka relations is less discussed, albeit equally significant.

Ever since President J. R. Jayewardene’s famous speech at the San Francisco Peace Conference advocating for the freedom of Japan in 1951, Japan has continued to be a staunch ally of the country. In fact, even as recently as 2009, Japan provided the most development assistance to Sri Lanka. However, China’s growing influence since 2009 consequently crowded out Japan. Therefore, the change of government in January 2015 and the subsequent foreign policy reset has provided Japan with a new opportunity to strengthen its relationship with Sri Lanka.

Politics in the South China Sea

Crucially, this development has taken place alongside growing tensions in the South China Sea region between China and its neighbours, including Japan. Due to growing tensions in the region, the United States and other regional partners have been keen to develop better relations with “smaller nations” in order to establish a unified front against the perceived aggression of Beijing. The G7 summit, in particular, was seen as an opportunity to reinforce the strategic importance of the region and its members’ concerns about China; a demonstration of its common strength, so to speak.

It is possibly due to a combination of these reasons that President Sirisena was invited as a guest of Japan to attend the G7 summit. This rationale is lent greater credence by considering the list of other non-G7 heads of state invited to the “outreach meeting” at the summit. In addition to Sri Lanka, the heads of state of Bangladesh, Chad, Indonesia, Laos, Papua New Guinea, and Vietnam were invited. The heavy regional focus and the importance of these countries with regard to China are especially obvious even to a casual observer.

For example, even though Chad has consistently performed badly in economic indices, Chinese investments into the country have flowed heavily in recent years. Similar to China’s policy elsewhere in Africa, aid and investment has been exchanged in return for access to oil and resources. Similarly, Bangladesh is a key location in China’s “Maritime Silk Road” but is at the same time attracting significant Japanese investments such as the Bay of Bengal Industrial Growth Belt (BIG-B).

What happened at the Summit?

As discussed above, the strategic importance of inviting Sri Lanka and a handful of other developing countries to the G-7 are quite evident. International gatherings such as the G-7 summit should not be analysed purely through a policy perspective since other dynamics make a significant impact on immediate and long-term foreign policy.

The subtle

Beyond policy statements and declarations, the tone and substance of diplomatic functions can be gleaned by analysing the behaviour of participants with each other. Therefore, it was quite interesting to watch the widely shared video of President Sirisena being received by other heads of state at the summit.

Diplomatic behaviour, especially during segments open to the public and media, is choreographed to the most-minute detail. In fact, body language and extra-linguistic signalling is considered to complement, illuminate, and supplement direct communication. For example, a historic handshake took place between President Barack Obama and President Raúl Castro at Nelson Mandela’s funeral, which signalled a shift in foreign policy between the US and Cuba that ultimately led to the re-establishment of full diplomatic relations between the countries.

Cognisant of this, the dynamics between President Sirisena and other heads of state were noteworthy. Firstly, it appears that leaders of the G7 are coming up to the Sri Lankan President, which demonstrates that intent on initiating better and stronger relations between the leaders and consequently, the respective countries.

Sri Lankan Presidents in years past have found it extremely difficult to arrange meetings with the leaders of the G7 and therefore, the initiative taken by these nations demonstrates the strategic importance placed on Sri Lanka. Secondly, it is also shown that the Sri Lankan President is placed at a very central position at the discussion table.

Organisers and Protocol Officers take weeks and sometimes months to finalise seating arrangements. And in this case, the leader of a small island is sat next to the Japanese Prime Minister (as his guest), flanked by the UK Prime Minister, and right opposite President Obama. It’s a powerful testimonial for Sri Lanka and a statement of intent to improve cooperation by the G7.

The obvious

The G-7 Summit rarely implements any concrete policies but rather uses the forum to improve coordination between members, communicate political stances, and set out a somewhat common direction for the economy. Therefore, the summit is essentially more talk than substance. Thus the summit, as expected, failed to lay out a concrete economic policy direction, but rather reassured observers about its commitment to improving global trade and investment flows while addressing other issues such as the migrant crisis, threats related to terrorism, and the South China Sea.

For Sri Lanka, therefore, more concrete policy decisions were made at the bilateral level with Japan. In this regard, Japan has pledged Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) to the amount of 38 billion yen, for the construction of national transmission and distribution and water supply facilities in Anuradhapura District and other development projects.

More importantly, however, in a joint statement released following the bilateral meeting, both nations “reconfirmed the importance of maintaining the freedom of the high seas and maritime order based on the rule of law”. This is undoubtedly in recognition of China’s activities in the Indian Ocean and the Japanese government has also pledged two patrol vessels as part of their maritime security operation.

What’s next?

The invitation to the G7 Summit and the reception given by heads of state to President Sirisena clearly indicates Sri Lanka’s realignment of foreign policy and recognition by other countries for this realignment. It is important to note, however, that realignment in foreign policy should not be at the expense of good relations with China.

Sri Lanka has much to gain in terms of economic cooperation, political support, and geopolitical security by securing a good relationship with both the East and the West. The success of a non-aligned foreign policy was most evident under the stewardship of the Late Lakshman Kadirgamar when he leveraged partnerships with the US and Europe to strengthen the country’s position at multilateral institutions to curb financial and political activities of the LTTE while also strengthening relationships with China and Russia on other fronts.

Therefore, Sri Lanka should learn from the previous Government’s mistakes and refrain from isolating ourselves from either partner. Thus, a smart foreign policy willing to engage with the whole spectrum of international partners needs to be advocated and pursued in the best interests of the country.