Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 8 February 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kithmina Hewage

By Kithmina Hewage

In October 2011, then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outlined a new foreign policy vision for the United States that rebalanced its focus to East Asia and Pacific from the Middle East.

Given the costly American interventions in the Middle East, the Obama administration believed that a diplomatic and military ‘pivot to Asia’ would best enable them to benefit from the economic dynamism of the region while also balancing China’s military strength.

At the time, the pivot to Asia was considered a demonstration of American intent to influence the balance of power in the region, as well as geo-politics and economics of the region. Six years on, however, it is the regional and global balance of power that appears to be pivoting towards Asia.

Following the announcement of the pivot, the American foreign policy establishment moved to strengthen its military capabilities in the region and these moves were most prominent with growing tensions in the South China Sea region. More important however, especially from Sri Lanka’s interests, was the economic strategy laid down by the Obama administration.

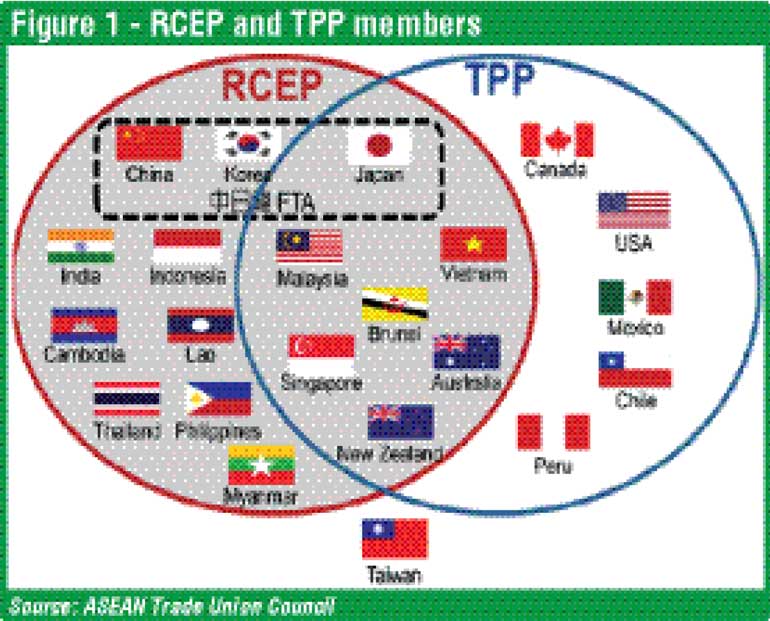

The crown jewel of Obama’s economic pivot to Asia was undoubtedly the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The largely US-led agreement included 12 Pacific countries that covered a significant share of international trade. Strategically, the agreement did not include China and also set out to dictate new rules for trade and investment while circumventing the gridlock of the WTO.

The regional economic focus was, therefore, two-pronged; undercut China’s growing economic prowess through trade alliances and reforms to trade rules, and tap into the economic dynamism of the greater ASEAN region.

However, President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ stance has completely overturned the expected trajectory of Asian politics. Rather than a more prominent role for the US in Asian politics and economics, Trump has called for a more protectionist and isolationist economic and foreign policy. Moreover, his ‘Buy American, Hire American’ stance could potentially undermine the role of the US as a leader in international trade.

One of his first actions as President was to withdraw the US from the TPP. Moreover, some quarters of the administration has also seemingly embraced a punitive tariff on Mexican and Chinese imports. If such a policy were to be implemented, the impacts on the American and the global economy will undoubtedly be catastrophic with close to one-third of American trade occurring with Mexico and China.

Trump has also demonstrated his disdain at regional trading agreements such as NAFTA. In withdrawing from the TPP and also pursuing a protectionist trade policy, not only has the US forgone the opportunity to gain from the benefits of the free trade agreement, but also the opportunity to mould the rules of trade in the 21st century. The regime’s ambivalence to regional trade and internationalism, therefore, has created an opportunity for a new leader to emerge in international economic relations.

Given their economic successes in the recent past, China’s rise, to at least some degree, was inevitable. In fact, China’s successes, along with those of other East Asian economies, have balanced the economic instability faced by their counterparts in Europe, and circumstances have ensured that China in particular, has the opportunity to truly ascend to become the new leader in international trade.

The irony is that, within the same week, the leader of the United States – the bastion of free trade – delivered an inaugural address promoting protectionism while the President of China – a communist nation – delivered an address extolling the virtues of globalisation at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Where the TPP failed as a mega-regional to dictate 21st century trade rules, China along with India is now touting the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). If successful, the RCEP is likely to present an alternate path towards trade liberalisation based on a more developing-country-perspective, compared to that of the TPP.

In addition to leading through mega-regional trading arrangements, China’s booming middle class allows them to transform the economy from an almost exclusively export-oriented economy to one that is more balanced.

China’s rise as a global leader in international trade could be particularly beneficial to small developing economies. Countries such as Sri Lanka will find it easier to make the incremental commitments needed to join a mega-regional such as RCEP rather than the complete institutional overhauls required for TPP accession.

Moreover, the rise of protectionism in the US and the expected instability in Europe due to growing nationalism and Brexit has made it abundantly evident that Sri Lanka needs to diversify its export markets.

The economic dynamism of the future lies in the greater-ASEAN region and the economy needs to make the necessary adjustments that can cater to these markets. In order to successfully do so, however, the country needs to urgently address fundamental economic reforms in trade and investment policy along with other institutional reforms.

Increasingly, investors from emerging economies (commonly referred to as ‘Third World MNCs’) are starting to move outwards towards other developing countries. Sri Lanka will be unable to attract these efficiency-seeking investments if it fails to establish a conducive economic environment.

Even the success of free trade agreements currently under negotiation with partners in the East will depend heavily on successfully implementing the required reforms and achieving a semblance of policy stability. Therefore, Sri Lanka needs to be cognisant and proactive in making best use of the pivot in global trading power towards Asia.

[Kithmina Hewage is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]