Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 28 January 2016 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Vijay K. Nagaraj

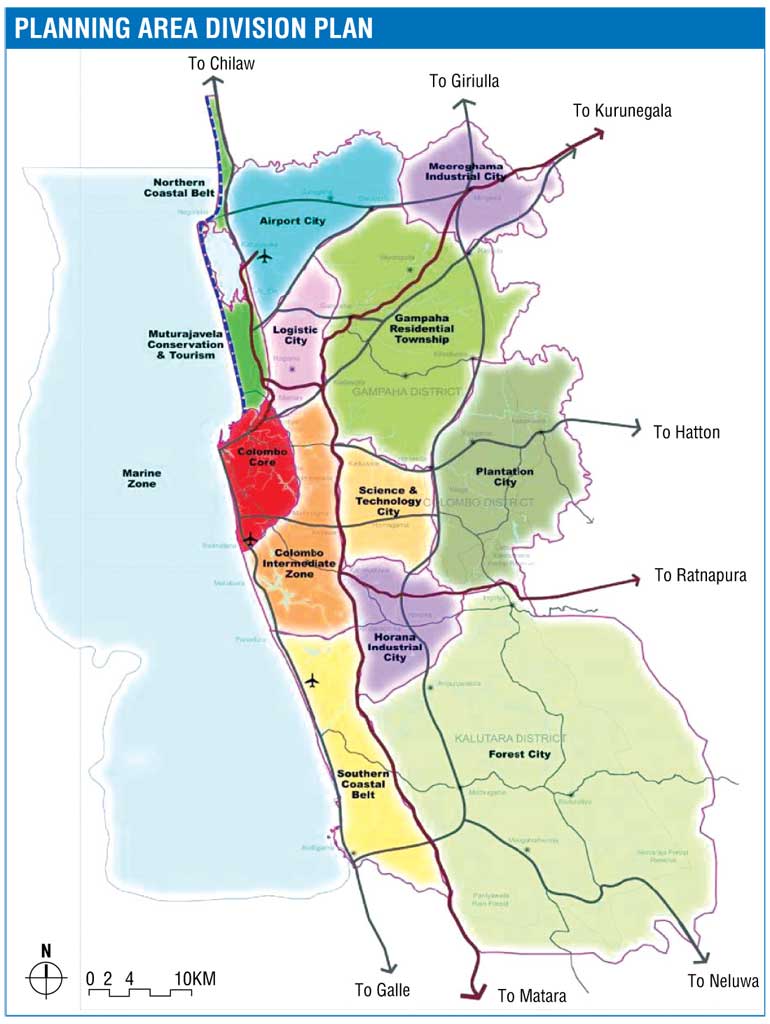

Recently, the Ministry of Megapolis and Western Region Development circulated an overview of the Western Megapolis master plan. The document’s sub-title – from Island to Continent – reflects the claims inside that the Western Megapolis is “Sri Lanka’s grand strategy to propel the country’s drive to achieve the status of a ‘high income developed nation’ by 2030”.

According to the overview, the Megapolis is the key to virtually every national development goal – from achieving self-sufficiency in food, energy, and pharmaceuticals to reducing poverty and unemployment to less than 1% to increasing exports to 30% of GDP and to transforming Sri Lanka into a knowledge economy, and so on. Yet, the overview signals a fairly narrow and formulaic vision of spatial and structural transformation, giving rise to many serious questions pertaining to social, economic and environmental justice.

Ideology at work

The overview is peppered with framings taken straight from the World Bank. These include ideas such as ‘messy urbanisation’ (sometimes clumsily paraphrased as ‘messy organisation’), the twinning of spatial transformation through planned urbanisation and the structural transformation of the economy, the accent on economies of agglomeration, and on removing ‘congestion constraints’. All of these seem to be borrowed from ‘Leveraging Urbanisation in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability’.

The launch of this World Bank report in Colombo late last year was presided over by Ministers Ranawaka as well as Hakeem. It has since become par for the course for Sri Lankan policymakers to speak the same language, sometimes even using the same slides in their presentations. Much of the framing and conceptualisation of the megapolis therefore appears derived and caught in the grip of dominant templates and ideas about development and urbanisation spun by powerful global actors and capital.

But the issue is not just one of relevance or of even one of ignoring insights from local research and scholarship but also one of ideology. It is in this context that we need to examine the ‘pillars’ of the proposed Megapolis: economic growth and prosperity, social equity and harmony, environmental sustainability, and individual happiness. Even from the limited information in the overview several serious questions arise in relation to these.

Growth, jobs and precariousness

The overview claims the Megapolis will create thousands of jobs through its ten core mega-projects. How exactly, for instance, the transport, water and energy sector will create 61,000 jobs or housing and relocation of administration will create 79,900 jobs and so on, remains unclear.

But what the overview is clearer about are the conditions under which these jobs will be created. It is all premised on assuming “pro-business labour policies allowing multi-national talents to work in Sri Lanka.” So what are the kind of jobs that will be created, for whom? What new structures of precariousness and opportunity can we expect?

The Megapolis is expected to be driving the transition “from labour intensive to skill intensive industries and to a knowledge-based economy.” What are the risks inherent in this transition? Who are the most at risk and how will they be protected?

These questions also have to be viewed in the light of other measures envisaged such as the shifting and relocation of industries. The experience from places like Delhi of relocating industries underlines the risks such moves present for workers as well as others integrated into and dependent on the local micro economies that emerge around these industries. There is little evidence that these issues are being considered.

Spatial injustice and social equity

An insight into the quality of economic growth and who is placed at its centre is also evident from the way spatial transformation is envisaged. For all, the talk is about social equity, the poor and working class will struggle to find space in the Megapolis.

The overview notes that “the underserved community regeneration programs are urgent; specially to release the economic corridors occupied by them.” In other words, the poor and working classes are an obstacle to realising the economic value of urban land.

So how much land, i.e. ‘economic corridor’ space, do the underserved settlements occupy? The figures for Colombo are instructive. Let us go with the widely cited figure that nearly 50% of Colombo’s (the city not district) population lives in so-called underserved settlements. And the Urban Development Authority (UDA) officials have often said that these settlements occupy nearly 900 acres.

The extent of the city of Colombo is around 37 square kilometres or about 9140 acres. In other words, nearly 50% of the population of the city occupies just under 10% of its area. But even 10%, we are told, is too much for the poor and they need to be further densified i.e. pushed into high-rises. Why does the Megapolis plan fail to recognise the extent of existing spatial inequality and actually call for measures that worsen it while claiming to be pursuing social equity? Why is there little more than lip service to equity and inclusion?

More than the poor occupying valuable lands, the truth is that lands occupied by the poor can be taken away far more cheaply and easily, especially if you simply dispossess them on the grounds that no title means no rights. The silence on committing to policies that do provide some equity safeguards, like the National Involuntary Resettlement Policy, is indicative of what the Megapolis may mean for the poor and working classes.

The sustainability and livability rhetoric

There is much talk in the overview about livability, sustainability, green connectors, green energy, eco-habitats, and so on. But there is no attempt to articulate livability or sustainability in terms of clear goals inter-connected with other planning dimensions. Such goal setting is crucial to benchmarking, setting standards and norms to ensure it does not remain just talk. But what does such integrated goal-setting look like?

Given all the looking at Singapore, it is worth considering how livability and sustainability goals are framed there. For instance, by 2020 public transport in Singapore is to account for 70% of journeys during morning peak hours. Similarly, by 2030, 8 in 10 households in the city are to live within 10 minutes of a train station, and energy efficiency is to be increased by 35%, recycling rate to 70% and domestic water consumption reduced to140 litres per capita per day, and there is meant to be 0.8 ha of green park space for every 1,000 persons.

The overview of the megapolis, dominated as it is by rhetoric and broad economic targets, gives no evidence of thinking along developing such integrated goals. By its own logic, such goals are crucial to guiding and ensuring consistency in integrated planning but they also demand attention to detail, rigour and indeed real commitment.

Apart from the Port City, there are large-scale transformation projects envisaged whose environmental consequences will be serious. Just take one: the development of “at least sixty new high-rise buildings of 40-floors or more” in the central business district of Colombo. Why “at least” sixty? What are the potential environmental effects, in terms of air circulation, aggravating heat island effects, water consumption, waste generation, and so on? Has there been rigorous modelling to consider all possible impacts?

Finally, more questions

The overview concludes by highlighting the importance of a ‘smart’ approach but is this just about digitisation and connectivity? How will this address or refract the many social and economic exclusions already present? What does it mean to simply prefix ‘smart’ to everything, as the overview does, from ‘government’ to ‘public services’ and ‘transport’ to ‘energy’ and even ‘nation’?

Any spatial and structural transformation project on this scale poses significant social, economic and environmental risks – clearly underlined by post-war urban development in Colombo. Yet, how is it that the overview envisages no risks at all, let alone social safeguards or economic or environmental risk management strategies?

The greater openness to public engagement – reflected in the public discussion in Colombo on the Megapolis hosted by Minister Ranawaka late last year – and the involvement of many well-known professionals is welcome. Yet, the overview raises so many fundamental questions and doubts reading the plan.

Even accepting the idea of a Megapolis in principle, can we accept an emphasis on action not coupled with attention to more careful thinking and planning, critical review, and considered execution?