Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 19 February 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rajakumari and Kurukulasingham holding a studio portrait of their missing loved ones

Text and Pix by

Shiran Illanperuma

Rajakumari keeps a UN booklet on human rights close to the studio portrait of her missing daughter, son-in-law and grandchildren. Nestled between the pages are copies of the letters she has written to various Government bodies, politicians and NGOs.

Rajiva, Surendrakumar, Sansiga and Harish had set off from Jaffna by bus, accompanied by around 60 others. They called Rajakumari from Batticaloa, revealing their secret plans to board a boat in Hambantota and seek asylum in Australia.

They were never heard from again.

Hard data on the numbers of the dead, or even missing, at sea are hard to come by. If boats capsized at sea, the bodies should turn up on local or international shores, say CID officials. But the Sri Lankan Navy say they have not recovered any such bodies and that most capsizes happen closer to Australian waters.

Rajakumari and her husband Kurukulasingham refuse to believe it, but their family members are likely among the 1,200 people that Australian Consul-General to South India Sean Kelly says “have died at sea trying to reach Australia”.

Lawyer and Human Rights Activist Lakshan Dias refutes these figures. “It’s not possible for the numbers to be so high when, just looking at the trips made from Southeast Asia to Australia, there can’t be more than 500 deaths,” he charged.

Dias also added that many of those disappeared at sea could have been apprehended by foreign navy and police forces and therefore be toiling in jails in South East Asian countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia.

Regardless of the true numbers, Rajakumari and the dozens of others like her who’ve lost family members in their efforts to seek asylum across the sea seem to have little to no legal recourse.

Rajakumari’s human rights booklet

Chairman of the Missing Persons Commission Maxwell Paranagama said a few families had approached the commission with cases of this nature, but following up investigations proved to be challenging.

“We sought information from foreign countries on the whereabouts of these people but none of these countries have responded so far,” he said.

Officials at the Vavuniya Police, where Rajakumari filed her complaint in 2013, say that such cases should be referred to the CID. CID officials in turn say that no such complaints have ever reached their ears.

Many relatives of people missing at sea say that they are too afraid to take their grievances to the relevant authorities, especially if they have been somehow complicit in their loved ones’ illegal departure from the island.

Under the Immigration and Emigration Act, it is illegal for a Sri Lankan citizen to depart from the island at an unapproved port or without a passport. According to lawyers those guilty of breaking this law can be slapped with a Rs. 100,000 fine, have their passport impounded or even face prison time. Legal basis also exists to prosecute the agents responsible for smuggling people in boats, especially if their passengers were harmed while at sea. “Under Sri Lankan law, if a person takes passengers out to sea a boat that is not seaworthy, they are liable to be charged with attempted murder,” says Dias.

CID officials say that arrests of agents are rare as most use untraceable pseudonyms and never meet their clients face-to-face. In most cases deals are made not with the agents themselves but with subagents, many of whom evade capture by fleeing the country.

Ultimately, Dias argues that “the Sri Lankan Government is constitutionally obliged to search for citizens missing at sea, bring back the bodies and see what happened to them,” though there seems to be insufficient capacity and political will to do so.

Undeterred, Rajakumari continues to write letters, fattening her human rights booklet beyond capacity. Her husband looks on stoically. With a weak heart and two failed kidneys, he is unable to join his wife’s petitioning.

Holding on to bitter hope, he says, “They could be caught by the Government and kept in secret camps, or maybe they are stranded in an island somewhere. We do not know. We cannot live without knowing.”

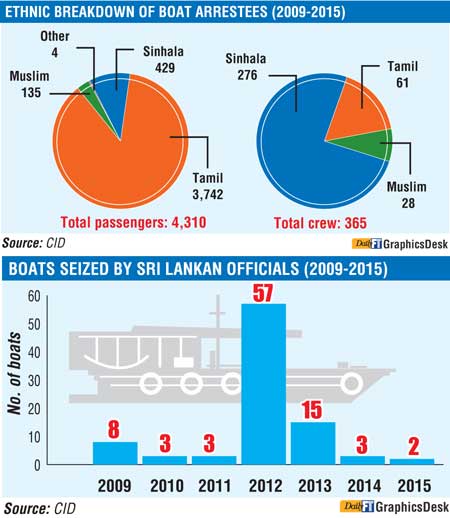

The number of arrests made by the CID of people trying to leave the island by boat has reduced by more than 96% from 2012 to 2015.

This reflects an overall decline in the number of people attempting to leave the island illegally, say CID officials. Sources in the CID say that since the end of the war in 2009 they have, with the help of the Navy, stopped a total of 91 boats attempting to leave the island and arrested 4,310 passengers and 365 crew members.

Despite the civil war having ended in 2009, recorded arrests by the CID spiked three years later in 2012 and 2013 – a reflection, the CID says, of the fact that larger numbers of people tried to leave the island for unknown reasons in these years. A report by the Australian Broadcasting Company in August last year revealed that the Australian Federal Police has provided material and intelligence support to Sri Lanka’s Criminal Investigation Department since mid 2009.

Officials at the CID have concurred that the increased crackdown on illegal departures from the island were possible due to support from the Australian Government and that the CID held regular meetings with representatives from the Australian Federal Police.

While the CID tracks cases and makes arrest before people leave the island, large numbers of arrests are made at sea by the Navy, which was the beneficiary of two patrol boats donated by former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott on his visit for CHOGM 2013.

Said Navy Spokesperson Captain Akram Alavi, “Thanks to assistance from the Australian Government we were able to reduce the number of people being smuggled significantly.” According to CID statistics, an overwhelming 87% of passengers arrested while trying to flee the country by boat were ethnic Tamils. By contrast 76% of crew members apprehended belonged to the majority Sinhalese ethnicity.

Captain Alavi says that despite most asylum seekers originating from the north and east parts of the island, the vast number of apprehended boats were from the south and west. While CID and Navy officials are were unable to explain these discrepancies, a number of returned asylum seekers as well as relatives of missing asylum seekers say that their agents alleged ties with politicians in the south.

However, these claims cannot be verified.