Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 16 November 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Structural reforms matter for growth, and the benefits of these reforms tend to increase when they are bundled together, a new IMF study finds.

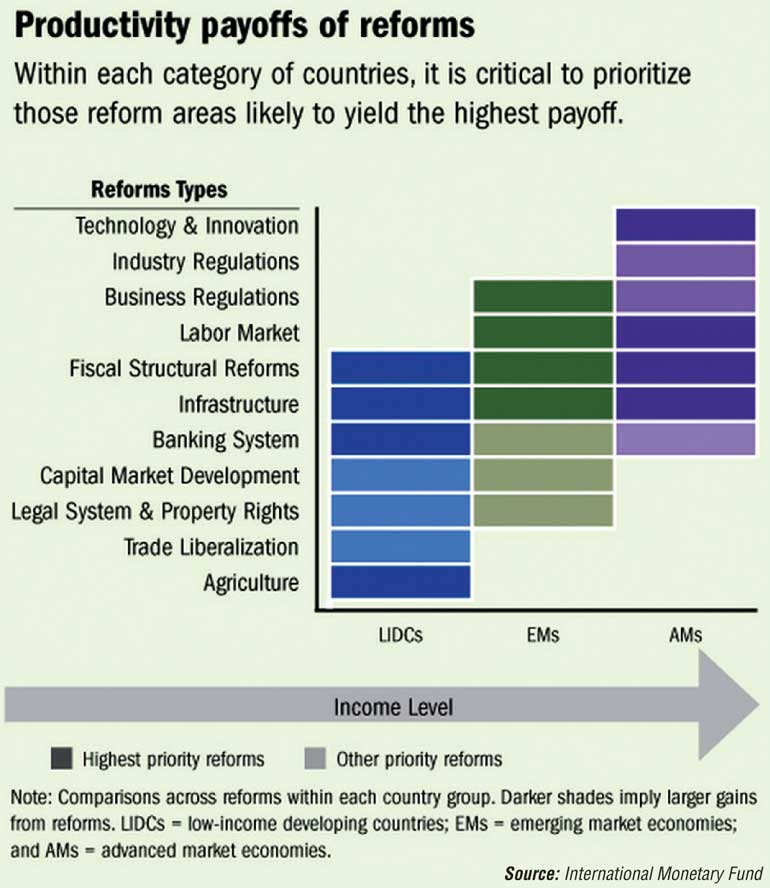

The potential payoff from different types of reforms varies across income groups—structural reforms that are typically more effective for a low-income country might not have the same impact in a country that is further along the development curve, the study says (see Chart 1).

But structural reforms alone are not a “silver bullet” for macroeconomic success, the authors stress.

“Strong country ownership and the ability to sustain reforms appear to be crucial for reaping the productivity and growth benefits,” says Sanjaya Panth, Deputy Director of the IMF’s Strategy, Policy and Review Department.

Reigniting growth potential

To achieve economic health, countries often need to make changes to the basic structure of their economies. Structural reforms are measures that aim to raise productivity by improving the technical efficiency of markets and institutional structures, or by reducing impediments to the efficient allocation of resources. These range from measures as diverse as banking supervision reforms and property right laws to changes in tariff rates or rules on hiring and firing.

The IMF is honing in on the role of structural reforms in boosting potential growth—a key challenge for policymakers since the global financial crisis, when many countries have been stuck in a cycle of lacklustre growth and high unemployment. Nearly all countries have seen a slowdown in productivity growth, with potential growth weakening in many cases as well.

In the six years since the crisis, many countries face a situation where policies to support demand and revive growth—such as fiscal stimulus and unconventional monetary policy—risk losing their effectiveness or are running out of space. In these circumstances, policymakers are increasingly turning to structural reforms to complement other efforts to jumpstart growth.

Although the fund has stepped up its efforts since the crisis to examine how structural reforms affect economic outcomes, the new study aims to help the IMF take a more strategic approach to structural reform areas that might warrant closer attention, as called for in the 2014 Triennial Surveillance Review.

“If the fund is to invest more systematically in supporting countries’ reform needs, we need to gain a deeper appreciation of the relationship between reforms and macroeconomic performance,” says Chris Papageorgiou, who co-led the study with Karen Ongley.

Drawing lessons from experience

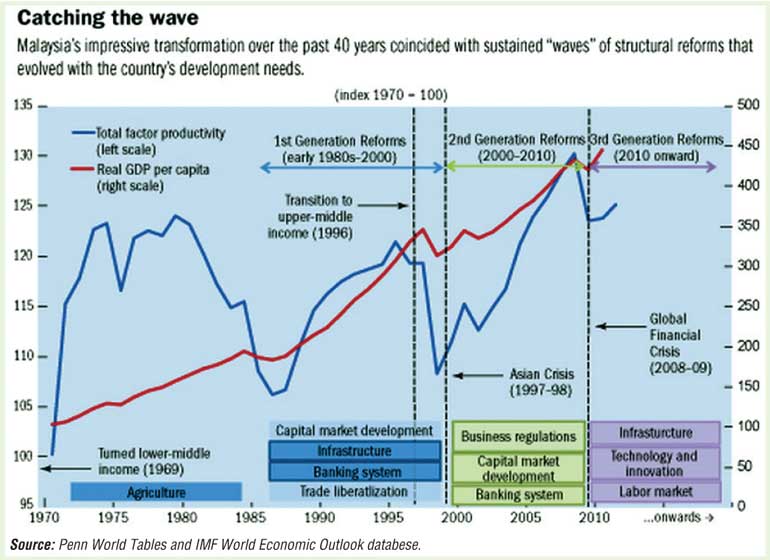

The study explores the relationship between broad reform trends and productivity, considering the implications of large-scale reforms as well as the impact of “waves” of reforms, where several reforms are implemented in parallel.

In both cases, the authors found a positive relationship between structural reforms and productivity growth. Even larger payoffs are observed when multiple reform episodes occur in parallel, the authors say, but further work will be needed to see how countries can combine and sequence structural reforms to yield the most effective results.

The study also confirms that fiscal structural reforms (such as measures to strengthen tax administration, spending efficiency, and budget processes) and financial sector reforms—both at the core of the fund’s mandate—were found to be highly relevant across the membership

In addition to examining data from the past 40 years, the study explores lessons from six country cases—Armenia, Australia, Malaysia, Peru, Tanzania, Turkey (see Chart 2). Their experiences tend to reinforce the findings of the empirical analysis. “The most successful reformers generally took a more comprehensive approach, where sound macroeconomic policies complemented structural reforms,” says Ongley.

The authors also surveyed IMF staff who lead country teams to gauge the relevance of various structural reforms in the current discussions with member countries. The results reinforce the idea that reform needs evolve as an economy develops. For instance, agricultural reforms are more likely to be relevant in low income countries, while innovation and labor market reform tend to be higher priority reforms for advanced economies.

Next steps

Building on recent efforts, the IMF plans to continue to develop a richer analytical foundation and range of diagnostic tools that country teams can leverage in their analysis and dialogue with member countries. Another aspect of this will be to help leverage and share policy experiences across different countries. As that work develops, the IMF should also:

• Be equipped to recognise all structural issues that are critical to the macroeconomic health of IMF member countries and highlight the macroeconomic implications in country consultations;

• Limit its specific policy advice to areas where it has the necessary expertise, but explore the possibility of building expertise in select areas of high impact and high demand, such as infrastructure and labour market issues; and

• Strengthen collaboration with other agencies on structural reforms that are outside the IMF’s core areas of expertise.