Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 25 January 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Janaka Wijayasiri

By Dr. Janaka Wijayasiri

Sri Lanka is currently engaged in trade negotiations with China, and five rounds of talks have taken place to date with the expectation of concluding discussions in mid-2017. Whilst such negotiations are ongoing, it would be prudent for Sri Lanka to examine the experience of one of its neighbours, Pakistan, with its Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with China to draw lessons before finalising the agreement.

Like Sri Lanka, Pakistan shares an extensive cordial relationship with China. To deepen this bond, Pakistan signed a FTA was signed with China in 2006, which came into effect in 2007.The agreement is divided into two phases, with Phase I ending in December of 2012 and negotiations for Phase II beginning in July of 2013.

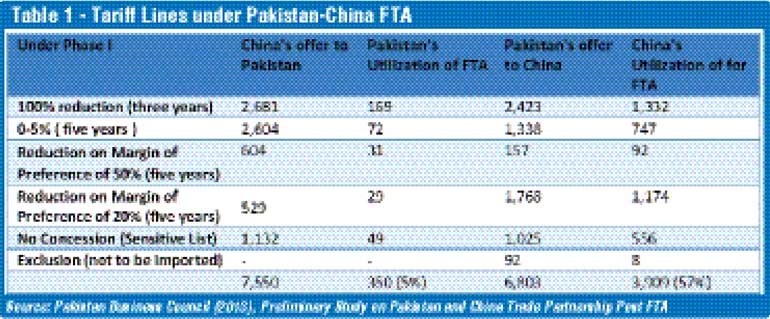

Under Phase 1, China agreed to eliminate/reduce tariffs on 6,418 product lines, and Pakistan made similar concessions on 6,711 product lines over a period of five years. Under Phase 2, tariffs are to be removed on 90% of tariff lines and trade volume, covering substantially all trade. However, Pakistan and China have yet to embark on Phase 2 of duty reduction under the FTA despite a lapse of three years.

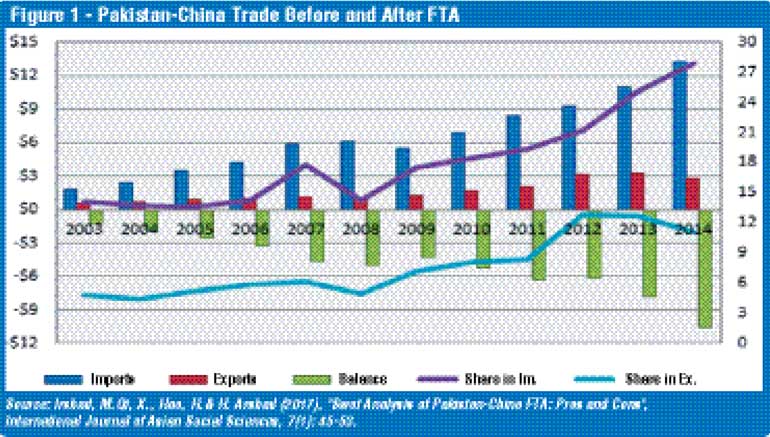

As of end of 2013, bilateral trade equalled $9,278 million, as compared to $3,421.96 million in 2006 prior to the FTA being implemented while the trade imbalance has grown in favour of China during this time (Figure 1).China has made substantial use of the FTA; it has managed to utilise 57% of the concessions under the FTA, compared to mere 5% in the case of Pakistan.

Tariff concessions extended to Pakistan appear to be generous at first glance (Table 1). However, nearly all top export products, including those in which Pakistan has a comparative advantage, China has awarded higher or equal tariff reductions to competing ASEAN countries. For example, tariffs under the 100% concession category were reduced to 0% by China for Pakistan by 2011; these products accounted for more than 35% of the total products offered concessions by China to Pakistan under the FTA. However, the average tariffs levied by China on these products for ASEAN countries were also 0%.

Even though there has been an increase in Pakistan’s exports to China subsequent to the FTA, growth of exports to China was also seen in products which were outside the scope of the FTA. In fact, many top exports of Pakistan to the world (and China) were placed in China’s ‘No Concession’ list. While China’s demand for these products was significant, Pakistan is currently contributing to less than 1% to China’s imports of these product lines.

China’s share in Pakistan’s overall exports remains below 10% while there has seen a significant increase in its shares in Pakistan’s overall imports. Post FTA China became the second largest source of Pakistan’s imports contributing over 25% of the total imports of Pakistan excluding petroleum products.

One way to obtain better access to the Chinese market is for Pakistan to renegotiate concessions so that they are equal to or more generous than those provided to other suppliers. Moreover, Pakistan appears to have failed to maximise the FTA despite tariff concessions by China. This may have been perhaps due to the fact that Pakistani businesses were not involved in the negotiation process. Thus, the first lesson to draw from Pakistan-China FTA is that Sri Lanka needs to ensure it gets similar or better concessions compared to China’s FTA partners, and to consult Sri Lankan businesses so that concessions negotiated are relevant to the interest of the country.

An analysis of the FTA by the Pakistan Business Council shows that even though 7,550 products (at 8-digit HS code) are covered under the FTA with China, Pakistan’s exports to China were concentrated in350 product lines (Table 1). In the zero rated tariff category, exports were recorded in169 products out of the 2681 products eligible for duty concessions. Nearly 1400 products covered by the Agreement recorded no exports from Pakistan to China or to the world. Conversely, concessions offered by Pakistan to China under the FTA appear to be more beneficial – both in terms of the coverage (number of product lines utilised) and variety of products (type of product lines utilised).

Of the 6,803 products covered by the Agreement and concession offered by Pakistan to China, imports from China were spread among 57% of the products (3,800 products) and product utilisation was more than 50% for the zero rated goods. In the case of Pakistan, the utilisation rates as was 5% for the zero duty items (350 items).

In this context, the second lesson for Sri Lanka would be to negotiate an FTA which includes products with high export potential as well as those which enjoy a comparative advantage against the rest of the world. Moreover, efforts should be geared towards diversifying the export basket, and this could be facilitated by export oriented foreign direct investments from China.

Trade imbalance between Pakistan and China is a cause for concern, as it is in the case of bilateral trade with Sri Lanka. China, one of the fastest growing economies of the world with imports of over $ 1.7 trillion, shares only $ 2.6 billion of its market with Pakistan in 2011. Share of Pakistan’s exports to China is only 28% of its total trade in 2011; the figure has increased from 15% in 2006. However, China retains the position of main supplier of many top products Pakistan imports. Consequently, the trade gap with China nearly doubled from $ 2.4 billion in 2006 to $ 4.8 billion in 2011.

The real challenge for Pakistan is not the trade imbalance per se but the unequal benefits that the two countries share because of the FTA. While exports have been increasing after the FTA, the loss of revenue to Pakistan is also increasing, offsetting any benefits that Pakistan is reaping from growth in exports.

However, the problem of trade imbalance cannot be addressed by discouraging imports from China as Chinese imports are important for Pakistan and tariff concessions to China have enabled local manufacturers to obtain cheaper inputs. A study on Pakistan and China FTA by the Pakistan Business Council argues that Pakistan should focus on increasing its exports and expanding local production of sectors where opportunity for trade exists to address the trade deficit which is the third lesson for Sri Lanka. It is noted that many products that are zero rated for Pakistan are imported in large quantities by China from the rest of the world and hence hold high potential for export growth if production/export is facilitated.

A preliminary study by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) regarding trade between Sri Lanka and China found 297 products with high trade potential to China; these products are currently not exported by Sri Lanka but are imported by China from elsewhere in the world, presenting new market opportunities for Sri Lankan exporters. In this context, Sri Lanka should recognise the opportunity these new sectors present to boost local production and exports to China and obtain tariff concessions for these products. Growth in such exports could potentially offset any losses in revenue that Sri Lanka will incur from exemption of duties to China under the FTA.

While zero rated category and other preferential tariff concessions to China have enabled Pakistan to import cheap raw material that is used in local production, tariff concessions to China under the FTA have also increased imports of finished products into the country. This has flooded the local market thereby lowering profitability and/or underutilised capacity of local producers in Pakistan. According to Irshad et al (2017), as many as 10 cases of anti-dumping have been filed by local producers against Chinese products to the National Tariff Commission and subsequently anti-dumping duties as high as 71% have been levied.

The study by the Pakistan Business Council recommends that Chinese imports, which have adversely affected the local producers as a consequence of the concessions offered by Pakistan, should be discouraged for a limited period of time (five years)so these industries could build up scale and competencies to compete.

This would be fourth lesson for Sri Lanka; it too should be mindful of its tariff liberalisation with China and identify sectors in the economy which may be adversely affected by opening up to China and provide a time bound support to these vulnerable industries. Moreover, Sri Lanka should urgently enact legislations on anti-dumping, countervailing and safeguard measures, which are temporary in nature to ease the transition toward freer trade and protect local industries against unfair trading practices/surge in imports.

(Dr. Janaka Wijayasiri is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To comment on the article, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics.)