Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 9 August 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The proposed Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Sri Lanka and China has once again become a contentious trade policy issue today among the business chambers and industrial sectors today.

The proposed Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Sri Lanka and China has once again become a contentious trade policy issue today among the business chambers and industrial sectors today.

This is largely due to the latest negotiation position where by Sri Lanka is expected (a) to reduce the negative list from 30% to 10% (b) to phase out import duty of 90% of the total tariff lines to zero duty over a period of 20 years and (c) to phase out the import CESS and PAL which has been imposed to safeguard the Sri Lankan industries to zero within five years after implementation of the proposed FTA.

The reduction of negative list takes place on linear-phased out basis of every five years and there is uncertainty over the method of selection of tariff lines as to which stage they fall in to this phased out period. Another concern is on what basis or criteria the remaining 10% negative or sensitive list is decided by negotiators.

China is currently the second largest trading partner of Sri Lanka and the second most important sourcing destination accounting to 20% of total imports in Sri Lanka in 2015. However, China does not at present contribute much to the Sri Lankan exports as it’s around 3% of Sri Lanka’s total exports. Some surveys done by researchers have identified that Sri Lanka has around 550 products for which Sri Lanka has the comparative advantage vis-à-vis the world including China.

According to Sri Lanka Customs statistics, Sri Lanka is already exporting 245 products to China. This means what we call under a best case scenario Sri Lanka has the potential to add around 250 more products to the present export basket to China under the proposed FTA. Now the million-dollar question is, can Sri Lanka do it? On what modular assumptions are these optimistic estimations made and have actual business environment/conditions been taken into the equations of such theoretical mathematical models?

Our enquiries from the Sri Lankan exporting community reveal that they face a range of trade barriers in the Chinese market. The commonly-cited issues include trade restrictive sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) regime compared to other export markets, non-existence of mutual recognition of standards and certificates.

A case in point is one of Sri Lanka’s major export commodities, tea, is subjected to a requirement known as ‘rare-earth content testing,’ which is unique to China. The compliance of this kind of testing requirement is problematic due to the lack of sufficient testing facilities in Sri Lanka. Sri Lankan testing facilities can only determine whether the rare-earth content is present or not in tea but the level of rare-earth content cannot be determined to meet Chinese requirements.

Also China does not recognise testing and certificates issued by testing and certification bodies by Sri Lanka. We understand that current FTA negotiations are focusing on so-called framework agreements which includes mutual recognition of products and services.

It should be emphasised that framework agreements will not establish mutual recognition of standards for products and services, since this is a very specific and technical task involving the bodies responsible for standards in the negotiating countries. Much resources in terms institutional and infrastructure capacities are required to harmonise standards and these cannot be merely relegated to mutual recognition framework agreements. There are concern whether the imports into Sri Lanka under duty free coverage of 90% goods will meet the Sri Lankan SPS standard. This will undoubtedly pause public health issues and other problems relating to the influx of sub-standard goods to the country.

The lack of transparency of test reports and the limits required in China are considered to be complex than other export markets. For examples in other export markets exports of shrimp requires to obtain an antibiotic test report only for one pond in the farm but in case of China antibiotic reports have to be provided for each and every pond in a farm.

On the other hand, obtaining quarantine requirements for fruits and vegetables are also extremely cumbersome and time-consuming and subject to a long approval process.

If we look at industrial exports to China such as textiles, apparels exporters complain stringent testing and specific requirements in China. This requires more detailed test reports compared to other export destinations and Sri Lanka lacks sufficient facilities to undertake such testing.

Taking in to consideration the concerns expressed by many countries, the World Trade Organization (WTO) in its fourth review of China’s trade policy called on China to address various NTMs such as anti-dumping duties, technical trade barriers, sanitary and phytosanitary issues, custom process, export restrictions and protection of intellectual property rights, etc.

FCCISL is of the view that entering into a FTA with China without addressing these trade barriers does not bring the expected benefits to Sri Lanka. On the other hand, Sri Lanka being a developing country which has serious issues on the competitiveness of its products due to high interest rates, low productivity, high production and labour cost will face serious consequences.

While FCCISL stands for free flow of goods without impediments and barriers among countries but admit the right of any country to safe guard its local industry against excessive imports. WTO too recognises the need for adopting safeguard measures for protection of domestic industries other than para tariffs imposed to achieve this objective. Phasing out the para tariffs, such as CESS, without the alternate WTO sanctioned Non-Tariff Measures will be a death knell and this step would lead to the closure of some of the local industries.

The Sri Lankan industrial sector is dominated by SMEs which accounts for 52% of the total GDP and is also accountable for 45% of total employment and accountable for 75% of enterprises. It’s also noteworthy to state that around 25% of these enterprises are owned by women. Moreover, SMEs are significant employers of women and youth. In the global agenda SMEs are receiving prominent attention; for example, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) under goal 8 recognise the potential of these businesses to support inclusive and sustainable growth and decent work for all.

These SMEs are dependent on large industries for backward/forward integration for supply sourcing of raw materials, marketing and other services. Removal of tariff protection such as cess will adversely affect these SMEs, both directly and indirectly which will lead to their non-competitiveness and closing down, creating unemployment and adversely affecting the economy.

The majority of the local industrialists have funded their investments, in their respective industries, with borrowed funds, from banks and financial institutions, using their personal assets as security. Further, their indebtedness on loans and overdrafts run into millions, depending on the size of the company. If they are not safeguarded sufficiently, it will lead to disastrous economic situations.

Sri Lanka has just concluded six rounds of trade negotiations with China and further negotiations are on the cards. Before concluding this trade deal, it would be prudent for Sri Lanka to examine the lessons learned by one of our neighbours – Pakistan – which entered into a FTA with China in 2006 and made it effective 2007. It should be noted that Pakistan is an economically greater entity and possess more production capacity than Sri Lanka, and yet has adopted a more cautious approach in its negotiations with China.

Pakistan and China signed an FTA in 2006 and made it effective 2007. Under Phase (1) of the agreement China agreed to eliminate/reduce tariffs on 6,418 product lines, and Pakistan was to eliminate on 6,711 product lines over a period of five years.

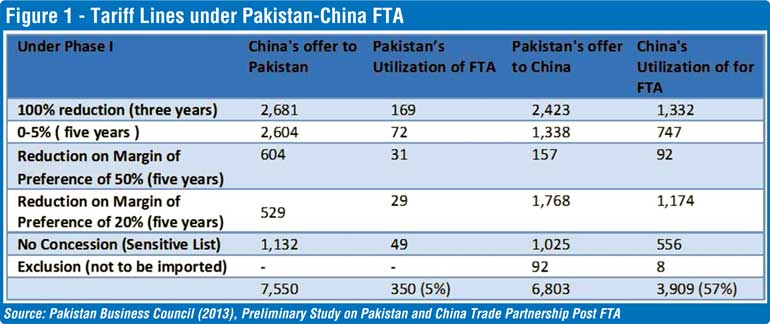

As of end of 2013, bilateral trade reached little over $ 9 billion, as compared to $ 3.5 billion in 2006 prior to the FTA being implemented while the trade imbalance has grown in favour of China during this time. It’s noteworthy to mention that during the phase (1) China made substantial use of the FTA and has managed to utilise 57% of the concessions under the FTA, compared to mere 5% in the case of Pakistan (see chart).

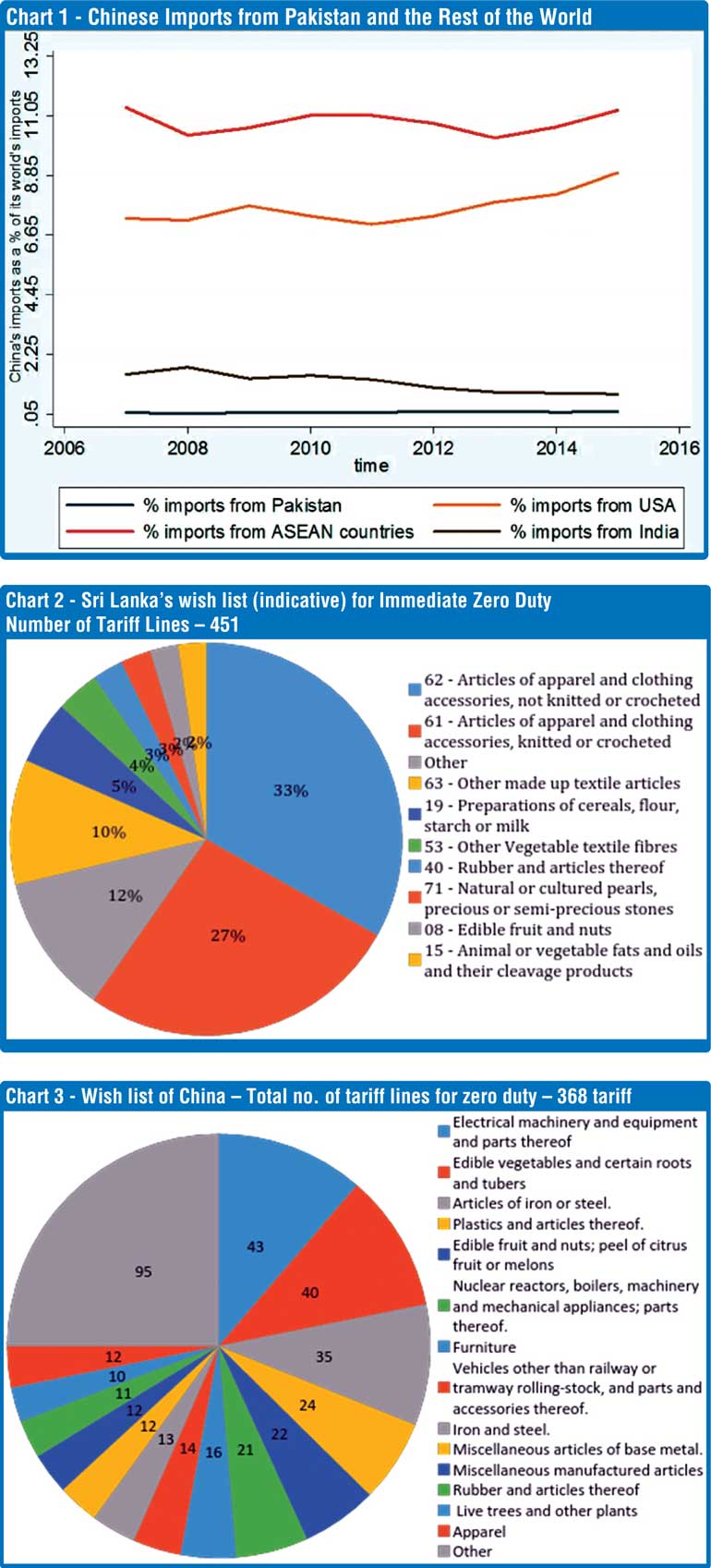

Has China effectively increased buying from Pakistan? What’s Pakistan’s position as an exporter to China compared to other countries which export goods to China after signing the FTA? The chart tells the story!

As evident from the chart on bilateral trade between the two countries over the last decade, Pakistan has failed to derive the benefits out of the FTA with China. In March 2017 Lahore School of economics and Pakistan Business council have attributed the following factors for poor performance:

China has awarded higher or equal tariff reductions to competing ASEAN countries for products for which Pakistan possess big export potential in Chinese market. As a result, tariff preferences enjoyed by Pakistan under FTS has been eroded which popularly known as preferential erosion.

During the negotiations Pakistan’s top exports to the world (and China) have been placed in China’s negative list despite the demand for such goods is high in Pakistan.

FTA concessions offered by Pakistan seems to be more beneficial for China both in terms of the number of product lines utilised and variety of type of product lines utilised.

At the time of signing the FTA between two countries, during the Phase (2) it was agreed to remove 90% of tariff lines achieving “substantially all trade’. However, no negotiation was begun even three years after the lapse of the phase (1) due to the refusal by Pakistan to commence the negotiations due to negative impact created by phase (1) on the Pakistan economy.

Uniqueness of Chinese system: It’s common knowledge that Chinese systems are not transparent in rules and regulations and business practices. Also, the competitiveness of Chinese goods internationally is largely due to their vast economies of scale, political and labour structure. Unlike in Sri Lanka in China there is no strict adherence to ILO labour conventions so all these factors give a huge advantage over cost of production in comparison to Sri Lankan products.

On the question of 90% liberalisation of tariff lines and submission of Government of Sri Lanka for such a demand at the negotiating table, we understand the asymmetrical nature of the FTA negotiations and the need for a representative negative list, the review clause has been put to the Chinese negotiators again and again during the past negotiations (despite the fact that WTO does not define what substantial coverage of goods for negative list should be), Sri Lanka has agreed to 10% negative list as requested by the Chinese. Its pity that Sri Lankan negotiators have accepted the Chinese stance at the loss of Sri Lanka’s economic interest.

It’s also important to properly analyse the real impact of China’s duty free exemption offer on some product lines amounting to 454 no sooner the import cess is removed by the Government. At a glance this offer looks very attractive, however the question is what tariff lines China will actually and finally offer duty free, which is not yet known to Sri Lanka! Sri Lanka had requested 451 tariff lines mostly comprising apparel and apparel related items, accessories, fibres, rubber and rubber related items, natural and cultured pearls, precious and semi-precious stones, edible fruits and nuts, animal and vegetable facts, etc. (see chart).

As you see among the wish list of Sri Lanka there are products with and without national advantage or competitive advantage, making the case weaker for Sri Lanka. On the other hand, China’s wish list consists of a well-diversified product range (see chart).

Another important factor is we should understand as to why China is stressing on 90% of trade liberalisation at an early stage with an unequal comparatively small trading partner as Sri Lanka.

Clearly, China has not taken into account the asymmetrical nature of the negotiations. We understand that under Multilateral Trading Rules it is possible for small developing countries like Sri Lanka to negotiate under Enabling Clause that offer more flexibilities. Negotiations of FTA between China and Sri Lanka are conducted under Article XXIV of GATT whereas Sri Lanka’s both FTAs with INDIA and PAKISTAN were concluded under the Enabling Clause. China too concluded its FTA with ASEAN under Enabling Clause that offers more flexibility.

Aren’t Sri Lankan negotiators aware of this basic principle? Even under the present rules of negotiations, there is no hard and fast rule that Sri Lanka should go in for a 10% negative list as requested by China. The WTO has not defined substantial coverage under Article 24 of the GATT to mean 10%. It is left for the countries to adopt a comfortable percentage as befits their economic and development level and negotiate long and hard.

In this context FCCISL having consulted its membership across the country wishes to suggest the following to safeguard the interest of the Sri Lankan business community:

(1) It’s important that while the negotiations are on for the FTA, the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) should address both tariff barriers and NTMs. This process should be part and parcel of the FTA negotiations.

(2) Adoption of a strategy of scenario planning on implications of FTA in two dimensions – the best case scenario and worst case scenario while taking into consideration the political, economic, social and technology factors.

(3) To include a time bound review clause as done in n the China-Pakistan FTA (see following excerpts from page 4 of the China-Pakistan FTA under chapter 3 – Article 8 – Tariff Elimination).

(a) Review and Modification of Tariff Reduction Modality and the Lists shall be as follows: (a) Tariff Reduction Modality and the lists shall be reviewed and modified every five years by the Committee on Trade in Goods.

(b) The review shall be undertaken on the basis of friendly consultation and accommodation of the concerns of the Parties.

(c) The first review and modification shall be undertaken either at the end of the fourth year or at the beginning of the fifth year of entry into force of this Agreement.

(d) Either party may request for an additional review at any time after coming into force of this Agreement. Such a request shall be favourably considered by the other Party.

(4) It is essential to have a strong development-friendly dispute settlement mechanism in the FTA.

(5) It’s critical that Sri Lanka gets similar or better concessions compared to China’s other FTA partners, e.g. ASEAN.

(6) Sri Lanka should urgently enact legislations on anti-dumping, countervailing and safeguard measures, which are temporary in nature to ease the transition toward freer trade and protect local industries against unfair trading practices/surge in imports. (However, the limits of such trade remedies in preventing the inevitable supremacy of Chinese goods in the domestic market should be noted. In order to establish dumping countervailing and safeguard action the WTO establishes particular rules that require to prove the alleged unfair business practices.)