Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 27 June 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

While many explanations could be found to describe Sri Lanka’s fate with exports, one key factor has been increased protectionism

By Ministry of Development Strategies and International Trade

Sri Lankan exports from the global context

The export sector experienced growth since opening up of the Sri Lankan economy. By 1990, Sri Lanka’s export share in GDP amounted to 25%.

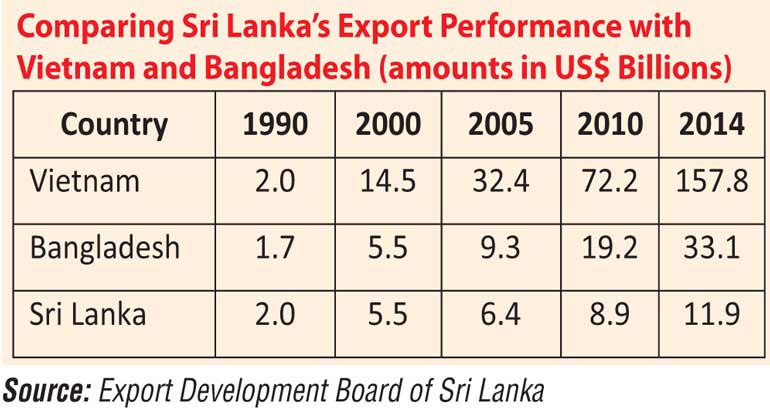

In 1990, Sri Lanka was on par with Vietnam exporting $ 2 b worth of exports per annum. By 2014, Sri Lanka’s annual exports amounted to nearly $ 12 b, but Vietnam had overtaken Sri Lanka and was exporting 13 times that of Sri Lanka with annual exports amounting to nearly $ 158 b.

Bangladesh, which was behind Sri Lanka in annual exports in 1990, had caught up and was on par with Sri Lanka by 2000 and was recording $ 5.5 b worth of exports. But by 2014, Bangladesh was exporting three times that of Sri Lanka with annual exports amounting to $ 33 b (see table).

This cross country comparison tells a larger story of what is happening domestically where exports as a percentage of GDP declined from 33% in 2000 to 14% in 2014.

Damage to exports

While many explanations could be found to describe Sri Lanka’s fate with exports, one key factor has been the increased protectionism that was granted. The latest World Bank report on Sri Lanka titled ‘Sri Lanka: Ending Poverty and Promoting Shared Prosperity – A Systematic Country Diagnostic’ (2015) explains the situation along the following lines:

“…in the last decade (since the mid-2000s) there has been a noticeable slide towards protectionism….. There has been an increase in para tariffs…. This has not only significantly increased nominal protection and prices of imports, but has also added to trade policy complexity. The combined system of the Most Favoured Nation applied tariff rates and the para tariffs has made the present import regime one of the most complex and protectionist in the world. Implementing para tariffs has effectively doubled the protection rates to 24%. Worse still is the para tariff dispersion, which leads to prices that distort production and consumption patterns. Last, higher rates of protection on final products than on imports used in their production lead to higher effective protection rates and an anti-export bias, because producers have strong incentives to sell goods domestically even though their domestic costs are higher than their opportunity cost through trade… Trade barriers also make it more difficult for local producers to access inputs, reducing their competitiveness and ability to integrate themselves in global value chains. Firms are also less likely to invest in capital equipment that would raise productivity and promote technology transfer.” (P.61)

The same World Bank report goes on to show that Sri Lanka was reversing the open economy by imposing such para tariffs when the “rest of the world was integrating more strongly and global trade was accelerating”. (P59)

In a number of instances para tariff protection has been granted as a protection measure. Some para tariffs have been used for raising revenue for the Government. By such action, a huge damage has been made to the Sri Lankan export sector as clearly articulated in the World Bank (2015) report. Let us illustrate an example of such protection from the one of the industries, viz., cosmetics.

Cost of excessive protection

Some cosmetic industrialists lobbied the Government for CESS (Commodity Export Subsidy Scheme) increase for cosmetic and nutraceuticals from Rs. 200 to Rs. 350 in 2010 as a protectionist device for the said industry. It came into operation from January 2011 and had several adverse impacts on the economy.

The Sri Lanka Cosmetic and Nutraceutical Trade Association (SLCNTA) said that the CESS increase was coming at a cost to the tourism industry and 58,000 salons that were using international brand cosmetics. The SLCNTA authorities went on to say that young people who were using cosmetics were deprived of buying brands that they always used to due to the high cost after the CESS was imposed. More than 90,000 jobs in the Cosmetic and Nutraceutical Sector were at stake (http://www.thesundayleader.lk/2011/02/20/slcnta-protests-new-rs-350-import-cess/).

The ultimate result is, this causes the export share declining in GDP and exports lagging far behind competitor countries as shown earlier. This loss is also reflected in Sri Lanka’s share in global exports declining during the last decade, indicating the erosion of the competitiveness of exports.

Challenge ahead

To rectify the Sri Lankan trading regime from such protectionist para tariffs will take some time. Sri Lanka needs to switch to export-oriented industrialisation where economies of scale could be reaped and more foreign exchange earned. Given the small market in Sri Lanka, import substitution industrialisation cannot reap economies of scale in the domestic market and save foreign exchange to match anywhere close to the foreign exchange earnings of export-oriented industrialisation.

It is vital to note that export growth can no longer depend on traditional export markets, such as US and EU, where demand is slack. Sri Lanka needs to find new markets and carve out easy market access to them. That is why the Government has embarked on a strategy to deepen the existing FTAs with India and Pakistan and work out new FTAs with growing Asian economies like China and Singapore.

Sri Lanka is currently at a juncture where it could no longer depend on debt-financed development. Debt repayment has become a huge burden on Government finance and debt has become costlier with the increase in global interest rates. Thus a viable development strategy that will bring in more foreign exchange to the country is needed via promoting exports and attracting FDI.

For export promotion, FDI will support to enhance the supply capacity to export and make best use of the wider market access gained via FTAs. Making this transition from debt-financed public investment and import substitution to a private sector–led exports and FDI-based development strategy remains a challenge. It is the only option available for Sri Lanka at this juncture.