Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 5 June 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

World Environment Day 2015 is marked today (5 June), under the theme ‘Seven Billion Dreams. One Planet, Consume with Care’. This article to mark the day highlights the importance of governing forest resources in a sustainable manner by restructuring the property rights systems

Striking a balance between development and natural resource management is important. An increasing population, urbanisation and development of infrastructure will demand more forest lands to be cleared. If there’s a lack of clear allocation of ownership, clearance of forest lands for development will be driven by political influence and bribes

By Chatura Rodrigo

Sri Lanka is rich in natural resources; filled with features including forest cover, coastal ecosystems, inland water bodies, fauna and flora and geological resources such as minerals and gems. While all these are equally significant in defining Sri Lanka, forestry resources attract particular attention since it is depleting at an alarming rate.

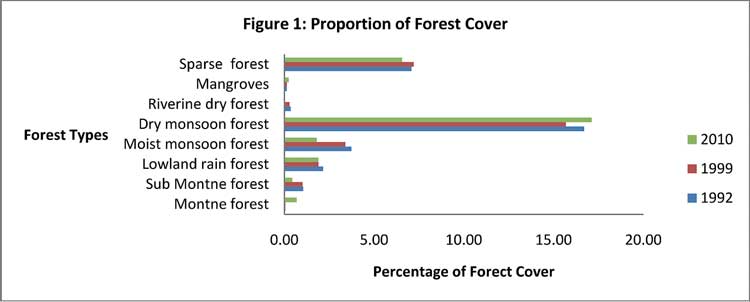

Forests produce many Ecosystem Goods and Services (EGSs) and provide an income for communities. The rising population’s demand for infrastructure and awakening of local economies have resulted in an increase in the deforestation for development and the extraction of forest resources for the increasing demand of forest products. However, it is important to manage forests in a sustainable manner, allowing sufficient consumption while ensuring inter and intra generational equity. The total forest cover of Sri Lanka has declined gradually from 31.23% in 1992 to 28.74% in 2010. Figure 1 below shows different forest covers and their depletion over time.

Forests produce timber and Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs). Commercial extraction of timber from protected forests in Sri Lanka is prohibited. Protected forests are governed by the Forests Conservation Ordinance of 1885 and land clearing and timber extraction is an offence. However, timber extraction can be done through plantation forests, especially grown to harvest timber. Furthermore, a significant amount of forest products derive from home gardens.

The most important NTFPs are medicinal plants, rattan, bamboo, products of hunting, products of kithul palm (Caryotaurens), edible plants, mushrooms, honey and pine resin. These products are extracted from forests in a sustainable manner and are directly linked to the livelihoods of people who reside close to the forests. However, despite the rigid legal framework and alternative forms of managing the timber demand, protected forests are still being cleared for timber and colonisation.

Management of forestry resources in Sri Lanka:

The current property rights regimes

Forestry is classified as a renewable resource. Given enough time, forests have the ability to grow back. However, the complexity of bio-diversity in forests needs a long period to restore. Therefore, if the extraction rate of the timber and NTFPs are higher than the restoration rate, the forest resources can deplete faster. In order to prevent this, like in all the other countries blessed with forest resources, Sri Lanka’s forests are protected by law, which prevents over extraction of forest resources by providing ample time for regeneration.

In theory, property right regimes that govern natural resources such as forestry always aim to keep the extraction rate of resources below the regeneration rate, allowing a buffer stock to be developed. However, misallocation of property rights can either result in over extraction, which leads to the ‘Tragedy of Commons’ or under extraction, which leads to the ‘Tragedy of Anti-commons’.

When forests are managed as an open access resource where no one holds the rights to manage and utilise forests, everyone has an equal chance of consumption and the probability for people to consume forest products without preserving for the future is high. This will result in over extraction and leads to the Tragedy of Commons. On the other hand, if the forest is managed by more than one entity with equal rights of exclusion, there’s a higher probability for under extraction, leading to the Tragedy of Anti-commons.

Property rights that manage forests of Sri Lanka hold characteristics that, if misallocated, can drive towards either one of these situations. For example, NTFPs are managed as an open access resource or a common property. The extraction of these resources from forests does not have a set limit. Such a property right regime does not have the capacity to prevent the extraction of indigenous medicinal plants.

Sri Lanka has a ‘red list’; fauna and flora are identified and categorised in order to take proper measures to prevent the extinction of endangered species. However, allowing open access can easily increase the probability of harvesting resources towards their extinction limit. Extraction of medicinal plants as a NTFP is a better example of this.

On the other hand, forest clearance for colonisation and development is highly regulated. Several Government institutions have the mandate to manage resources in a forest and institutions – the Department of Forestry, Department of Wildlife Divisional Secretariat Office and Ministry of Resettlement are some of those. Such a property rights regime holds the characteristics of an Anti-commons property.

When forest lands are to be cleared for timber extraction and colonisation, it is required to obtain the necessary permission from all these institutions. Such a property right system can discourage development and open the probability for forceful clearance of forests under political influence and bribes. Therefore, managing forests under an Anti-commons property regime would drive the underutilisation of forests and result in the Tragedy of Anti-commons in the eyes of development.

The way forward

Striking a balance between development and natural resource management is important. An increasing population, urbanisation and development of infrastructure will demand more forest lands to be cleared. If there’s a lack of clear allocation of ownership, clearance of forest lands for development will be driven by political influence and bribes.

If management rights are clearly defined without lapping jurisdictions, clear and transparent decisions can be taken on whether or not to use a particular forest land for development. Therefore, it is important that management of forest lands for development is vested with a minimum number of Government institutions that are less likely to be influenced by political pressure or bribes.

Despite drawbacks in terms of forest cover decrease and biodiversity loss, deforestation for colonisation and development present opportunities. Rather than clearing forests just to build houses and buildings, forest clearance for development can be done through a more sustainable and coordinated manner. In a colonisation process, private land titles are mostly given to people.

However, these land titles do not reflect clear characteristics of private property rights. Instead they are permits issued by local government authorities. Clear ownership of private land can significantly motivate the implementation of satiable land use management practices. The colonised lands can be easily converted in to successful home gardens. It can also be encouraged to grow timber products that have a significant demand in such land lots, which will help restore the loss of bio-diversity to a certain extent.

Community forestry is another significant initiative to manage forest resources in a sustainable manner. Community forestry management systems promote; alternative livelihoods, collaborative management of specific forest areas to control illegal extraction of timber or the unsustainable harvesting of NTFPs, collaborative management of specific forest areas with community participation, along with awareness and fire control measures. It also promotes improving home gardens to provide a source of timber, materials for stakes and trellises, and fire wood that are easier to collect and helps avoid forest degradation and the development of woodlots.

In this initiative, the forest land is owned by the state and its representative the department of forestry while the management rights are given to the people. Therefore, compared to an open access regime, this will help monitor the use of forests resources by the regulating authority.

Plantation forestry is also a major source of timber in Sri Lanka, which is in operation since 1870s. While there are Government owned plantation forestry establishments, there is an increasing emergence of private ventures.

The main property right regime that drives these private ventures is the private property. One approach is that, the people can invest in the land and then purchase plants from the private company and sell the trees back once they reach maturity. This provides the land owners the responsibility of managing the timber lot. The other approach is to invest in the land lot owned by the private company where people can only own the timber trees.

Finally, forest based eco-tourism initiatives have also proven to be useful in sustainable forest resource management in Sri Lanka. In this approach the forest land is privately owned by the operator of the eco-tourism venture and managed in such a way that it preserves the bio-diversity of the environment. Interested tourists can visit these lands and pay a fee in enjoying the environment. Tourists are not allowed to consume forest products. The approach has now been successfully expanded in to tea and rubber sector also.

This system of eco-tourism has proven to be more sustainable in managing forests than the usual way of managing forests by government institutions. Since the forests are privately owned, they are managed well and kept at its best to attract more tourists and support many local livelihoods.

[The writer is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view the article online and comment, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics).]