Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 9 August 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Lloyd F Yapa

This paper is about ways of dealing with the various objections to the reforms proposed during the last couple of years, to enhance the wellbeing of the people.

A grave economic crisis is facing this country. The elements of this crisis are:

a) A heavy external debt ($ 46.6 billion or 57.3% of Gross Domestic Product/GDP) by end 2016, inability to service the debt due mainly to declining export earnings (33% of GDP in 2004 to 13.5% of GDP in 2016) mainly due to an anti-export bias and an inadequacy of goods and services for export;

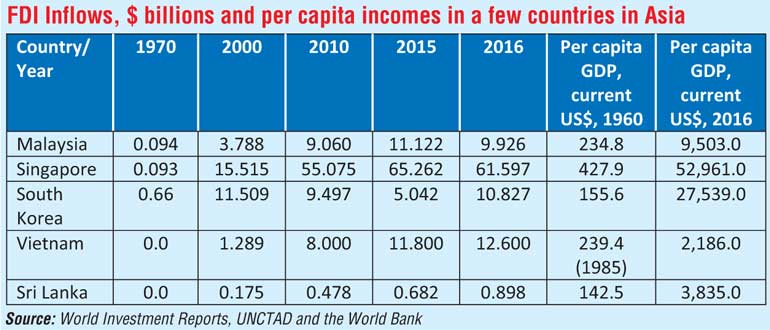

b) A trickle of investments particularly Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) (see table) required to create employment opportunities and to produce sufficient goods and services due to a persisting risk in the enabling environment accompanied by cumbersome regulations which increase transaction costs;

c) An absence of socio-political and macroeconomic stability made worse by a low Total Factor Productivity growth rate of -1.48 between 2010 and 2014 (Conference Board Data Base), which lowers export price competitiveness.

This has been the feature of the Sri Lankan economy since 1956, except during a short spell after 1977 when an effort was made to liberalise the economy in order to realise global competitiveness. Poverty and destitution (those earning less than $ 2.50 per day per person: 32.1% and those earning less than $ 1.25 per day per person of 3.2% of population in 2012/13, World Bank) therefore were never seriously tackled.

The main reason for this has been the failure on the part of the politicians, the media and teachers to create an awareness among the people of a vision and strategy that poverty and income inequality could be alleviated in a small country like Sri Lanka mainly by investing to produce competitive value added goods and services on a large scale (to reduce unit costs) for the global market, as well as by land consolidation to improve agricultural productivity and incomes of farmers and not by adopting the Marxian strategy of levelling down of incomes or indiscriminate dispensing of subsidies.

When there is such an awareness, people would tend to pressurise politicians to adopt the necessary national economic reforms without emphasising on individual needs and placing unnecessary obstructions in the way.

So now the necessity is to create such a vision and communicate it continuously among the people by the political leaders, the intelligentsia and the media. Although the present government declared in 2016 that the goal of economic policy is to enhance the wellbeing of the people and followed it by specifying in its second Budget that it would be on the basis of the Sustainable Development Goals approved by the UN (a few of the goals of which are: no poverty, zero hunger, good health and quality education), it failed to create the type of public awareness particularly of the means (e.g. investment) by which they are to be realised and the benefits that could be derived there from.

One of the reasons for this was the Government’s inability to win the trust of the people in the efficacy of its efforts, due to the absence of consultation, policy transparency/consistency and the failure to deliver on the major election promises such as curbing bribery/corruption, creating new jobs and arresting the decline in exports, especially in the short term.

The widespread violent demonstrations, protests and strikes that have been taking place in the country recently objecting even to essential development proposals and reforms introduced by the Government could be the results of this inability to create awareness of the type mentioned above along with the lack of public trust.

Some of these protests could be for genuine reasons, while others could be due to mischievous and political reasons. The latter types apparently are supposed to be due to what is described as ‘competing commitments’ (CCs), or personal or political reasons for resistance against the changes proposed, according to organisational psychologists, (Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, The Real Reason People Won’t Change, Harvard Business Review, February-July 2015).

The recommended professional ways of overcoming such CCs are:

a) Preparation of the ground in advance especially by pointing out the gravity of the current situation

b) Formulation of a vision in consultation with stakeholders to solve the crisis

c) Continuous communication of the vision along with strategies for reaching a solution effectively, while explaining the purpose and the expected results

d) Education of those objecting to the vision and strategies to overcome any serious CCs

e) Winning over powerful groups which could convert others to the vision and strategies proposed

f) Implementation of the strategies, while realising short-term successes to create trust among the people

g) Conversion of the vision and strategies into a national culture in terms of social norms, values and behaviour among the people so that they contribute positively without being prompted

(John P. Kotter, Leading Change, Why Transformation Efforts Fail and other articles on the subject, Harvard Business Review, February-July 2015).

The most serious among the various objections raised is the statement issued by the most venerable bhikkus of the three nikayas (or sects) in the country against the setting up of a new constitution which is absolutely essential for improving the country’s socio-political stability, for achieving the general wellbeing of the people and poverty alleviation particularly by creating a positive enabling environment for investment mainly by FDIs as they possess the necessary capital, technologies and world market access for products, that the local investors lack.

Why then did they object to a new constitution despite the higher wellbeing that will accrue to all citizens? There seems to be a competing commitment (CC) behind this objection; the Sangha (the Buddhist clergy) in Sri Lanka were compelled to assume the role of being guardians of the country, the nation (the community) and religion (rata, deya, samaya), in the face of a series of foreign invasions from South India up to the 15th century and from the West after that (Ven. Moragollagama Uparathana, Politics and the Role of the Sangha Community in Sri Lanka; Asanga Tilakaratne, the Role of the Sangha in the Conflict in Sri Lanka, Journal of Buddhist Ethics, Vol. 10,2003). Is this valid currently, is the question.

Take for instance the duty of protecting the country. After 1948, Sri Lanka is an independent country with no danger of being invaded by any external enemies. It is also a democracy where a government elected by the people with the rest of the State is responsible for security, law, order and economic development.

For instance the current Government was elected by the people of all communities to carry out this responsibility in 2015/16; it is clear therefore that it is the state which is responsible for safeguarding the country at present.

Regarding the responsibility of safeguarding the community (referred to as ‘the nation’ in historic times), at present, there is in Sri Lanka not one single community but a nation with a number of different communities observing different religions, who are all citizens of the country with a genuine desire to realise prosperity.

Granting favours to one community or disregarding the rights of others would not help as it might lead to ethnic unrest, possibly to separation and prevent the realisation of the announced national goals and targets. In fact some events that took place after 1956 had such adverse effects on the social, political and the economic stability of the country, particularly by raising the risk of separation and prevented the realisation of prosperity. These include the 30-year war waged by LTTE terrorists, claiming that the Tamils have been discriminated against and therefore that they have a right to separation.

Even if de facto separation does not take place, if the various communities in Sri Lanka resort to conflict, investors including FDIs for example will continue to avoid the country leading to a worsening of the economic crisis,( see the table below); the appropriate strategy to be adopted then is to formulate a strong new constitution and other relevant laws, as in the case of India or the USA, that will bring about reconciliation among communities by ensuring equal rights for all citizens irrespective of race or religion or caste, with devolution in respect of provincial issues.

Therefore the question the country faces is whether the right course is to resist the setting of a strong new constitution citing the possibility of separation by the minority communities or supporting it so that it instead could help all the communities to integrate into a strongly-knit Sri Lanka with a will to compete with the rest of the world to speed up economic development.

Where religion is concerned, the clergies of different faiths have to take into consideration the rising trend of intolerance, indiscipline, widespread addiction to intoxicants as well as an increasing rate of crime such as bribery, corruption, burglary/robbery, ransom demands, abductions, terrorism, rape, murder, etc.; if not curbed, it could increase the risk of investment for production of goods and services and proliferation of jobs.

Where this issue is concerned, the clergy of all faiths therefore faces the question whether it is not appropriate to take stock of what moral help is needed particularly by the youth and organise themselves to teach values that will help them to steer clear of harmful or illegal activities and concentrate on living a life useful to oneself and to society, while supporting the above vision.

Thus the necessity right now is to overcome the current wave of resistance to economic development. This could be achieved by solving the genuine problems faced by people and replacing the ‘competing commitments or CCs of other individuals, political and other groups, with a vision that will emphasise for instance on the need for investment to create jobs and produce goods and services especially for export; the latter is perhaps the only way a small economy like Sri Lanka could move forward on increasing real incomes and alleviation of poverty, as demonstrated by Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore; otherwise the country could be sure to move backwards to be a failed state like Somalia.

(The writer is a development economist.)