Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Friday, 22 May 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

W.A. Wijewardena, following the response of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka to his article ‘The continually loss-making Central Bank puts nation on red alert’ that appeared in Daily FT on 11 May, has issued a sequel entitled ‘A Central Bank missing the main point puts the nation on ‘extra’ red alert’ (Daily FT, 18 May 2015).

The Central Bank reiterates that the main point of the bank’s response is that its profits or losses must be treated differently to the financial outcomes of a profit oriented institution, given that the role of a central bank is not to be a profit centre but to meet specified macroeconomic objectives. Regrettably, it is Wijewardena who has missed this main point, and instead prioritises what is considered in central banking circles to be a “distant fourth consideration” in terms of the responsibilities of a central bank.

Wijewardena terming the Central Bank response as “flimsy” at the outset is misguiding and serves to create a judgmental bias, preventing the readers from weighing the evidence and forming their own conclusions. As Wijewardena chooses to escalate this fourth-order concern of a central bank a step further to an “extra red alert” level, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka wishes to draw attention of the general public to the following considerations:

1. Central bank profit/loss is a concern, but to a lesser extent than its concerns on macroeconomic objectives

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka never argued that its profits or losses are unimportant. Its stance is that the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, similar to all other central banks in the world, is mandated to deliver specific objectives, irrespective of the impact of such operations on its profits or losses.

The short article titled ‘Central Ba nks and the Bottom Line’ by Barry Eichengreen and Beatrice WederDi Mauro (2015) referred to in the Central Bank’s previous response is worth quoting at length. They accept that central bank balance sheets are increasingly gaining attention around the world and that “central bankers also do not like losses”. Nevertheless, they argue that central banks are “not profit oriented businesses. Rather, they are agencies for pursing the public good. Their first responsibility is hitting their inflation target. Their second responsibility is to help close the output gap. Their third responsibility is to ensure financial stability. Balance sheet considerations rank, at best, a distant fourth on the list of worthy monetary policy goals…It follows that a consideration that ranks only fourth in terms of priorities should not be allowed to dictate policy.”

nks and the Bottom Line’ by Barry Eichengreen and Beatrice WederDi Mauro (2015) referred to in the Central Bank’s previous response is worth quoting at length. They accept that central bank balance sheets are increasingly gaining attention around the world and that “central bankers also do not like losses”. Nevertheless, they argue that central banks are “not profit oriented businesses. Rather, they are agencies for pursing the public good. Their first responsibility is hitting their inflation target. Their second responsibility is to help close the output gap. Their third responsibility is to ensure financial stability. Balance sheet considerations rank, at best, a distant fourth on the list of worthy monetary policy goals…It follows that a consideration that ranks only fourth in terms of priorities should not be allowed to dictate policy.”

The former Bundesbank President Axel Weber is also widely quoted in discussions on central bank financial outcomes: “the Bundesbank profit is a residual issue for me and my colleagues...I don’t enter into any strategic considerations about Bundesbank profits, neither in the morning, afternoon or evening… We are instead striving to carry out our many tasks with the most efficient use of resources possible.”

Closer to home, ample evidence on this understanding of the concept of central bank profits could be seen in the writing of John Exter in his 1949 ‘Report on the Establishment of a Central Bank for Ceylon’. Wijewardena chooses to narrowly interpret Exter’s comment on what is now Section 39 of the Monetary Law Act (MLA), and states that “building capital funds is an anti-inflationary measure.”

What is ignored is the fact that, Exter with his broad understanding of central banking, did not limit anti-inflationary tools available to the Central Bank to an accounting policy on profits and losses. Instead, similar to other central banks, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was provided with appropriate monetary policy instruments in order to achieve macroeconomic stabilisation objectives.

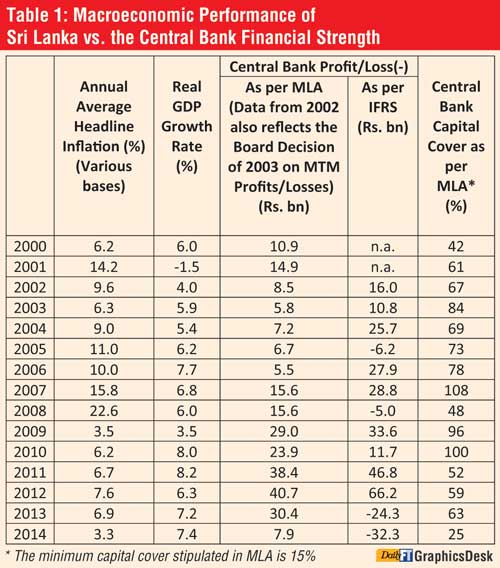

2. Macroeconomic performance vs. the Central Bank financial strength

Table 1 provides some indicators of Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic performance tabulated against the Central Bank’s financial performance. In some years where Central Bank profitability and capital cover have been high, the country’s macroeconomic performance has been weak. This relationship can be explained through underlying central bank operations to address the weaknesses of the economy from time to time.

Nevertheless, there is no clear evidence to indicate that the Central Bank profitability and the capital cover have been major contributory factors in improving macroeconomic performance in Sri Lanka. This is particularly true for the post-conflict period. Therefore, Wijewardena’s argument that “a central bank should avoid [making losses] by all means” is not valid. In contrast, as shown in the literature as well as in the Exter Report, it is more important for a central bank to focus on achieving its macreconomic objectives.

3. Foreign assets of the Central Bank vs. currency issue

Comparing currency board and central banking arrangements, Wijewardena states that “in the case of central banks, there is no legal requirement to back the currencies they issue by such foreign exchange balances and therefore, they could misuse their power to issue more currencies than necessary and thereby grow like an inverted pyramid. But the ultimate result of such a strategy is inflating the economy.”

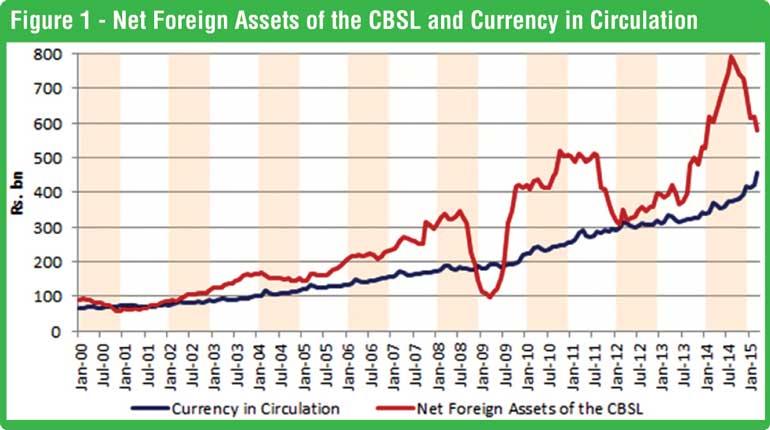

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka wishes to point out that a key reason for the establishment of a central bank replacing the currency board in 1950 was the rigidity of the currency board arrangement in addressing domestic concerns. Nevertheless, a comparison between net foreign assets of the Central Bank with its currency issue over time (see Figure 1) shows that the fear that Wijewardena highlights is unfounded, notwithstanding the level of the additional capital cover.

4. Central Bank reserve management in recent times

With regard to international reserve management, Wijewardena argues that “central banks should consciously target the highest level of profits they could make, but without putting the nation’s foreign reserves to unnecessary risks”. However, when global interest rates are low, the benchmark against which the reserve managers are expected to perform could even be negative. In this regard, Axel Weber’s comment on Bundesbank’s profitability that “only small profits should be expected in an environment of low interest rates and currency risk” is worth noting.

Nevertheless, international reserve management activities of the Central Bank has achieved a 4.4% realised return, on average, during the period 2007-2014, in spite of recording lower returns in 2013 and 2014. The average rate of return of reserve management activities including unrealised gains or losses during the period stood at 2.1%.

5. Relevance of the 15% minimum capital cover

Readers are invited to revisit the previous response by the Central Bank to assess whether the Central Bank has wrongly speculated about the wisdom of the Board in 2002, as Wijewardena has suggested in his latest article. What the Central Bank’s previous response stated was that “with regard to the capital cover, Wijewardena recalls that in 2002, the Monetary Board decided to gradually raise the capital cover of the bank to 100% of its domestic currency denominated assets.

Maintaining a 100% capital cover is unusual for any financial institution, but this may have been based on judgment of the Monetary Board at that time. Subsequently, the Board had decided to revert to the original provision of the MLA of at least 15% of capital cover.” Under no circumstances did the Central Bank’s response link the Monetary Board decision in 2002 to the “oncoming tsunami”.

The Central Bank response then went on to explain briefly that the influx of foreign funds following the tsunami along with the appreciation pressure on the exchange rate and sterilisation efforts would have influenced the asset structure of the Central Bank (including net domestic assets and its components of net credit to the government and net other liabilities) as well as the thinking of the Monetary Board in the post-tsunami period in relation to profit distribution.

Wijewardena argues that “the Central Bank and its Monetary Board have shown their unfamiliarity of the role of capital funds in a central bank” by deciding to revert to the original MLA provision of at least 15% of capital cover. This decision by the Monetary Board followed the capitalisation of reserves of the bank through appropriate amendments to relevant legislation to increase its capital to Rs. 50 billion by end 2014 from Rs. 15 million that had remained unchanged for decades since the inception of the bank until 2007.

Robert E. Hall and Ricardo Reis, in a 2013 paper entitled ‘Maintaining Central Bank Solvency under New Style Central Banking,’ discuss whether a central bank’s accounting capital matters just like in a private corporation. According to them, “the traditional measure of a corporation’s financial standing is the accounting measure variously termed capital, equity, or net worth. There are typically three reasons to measure it: to calculate the residual winding up value of the corporation, to assess its market value, and to ascertain the weight of equity versus credit in the firm’s funding.”

Hall and Reis show that “none of these reasons applies to a central bank. Central banks cannot be liquidated because their creditors cannot demand to convert their credit into anything but what they already hold, currency and reserves. Therefore, there is no meaning to the residual value of a central bank because the central bank cannot be wound up. Central banks also do not have a meaningful market value, since their goal is not profits, and shares in the [central] bank are typically not traded. Finally, governments own the central bank, they often deposit funds with the central bank, and most of the assets of the central bank are government liabilities. The traditional distinction between equity holders and credit holders is blurry and confusing for a central bank.”

Hall and Reis’s argument above is a generalised one, which could be disputed using extreme examples from the real world. Nevertheless, the ability that the central banks of Chile, Czech Republic and Israel have displayed in maintaining their prime objective of price stability while carrying a negative net worth for long periods of time makes the relevance of capital in the context of central banking doubtful. A number of central banks in other countries have also operated with negative net worth in certain periods in history.

6. Central Bank independence and financial strength

The relationship between central bank independence and its financial strength is an aspect that was not discussed in Wijewardena’s article on 11 May 2015. This relationship is occasionally discussed within the Central Bank and the Bank is in agreement with Wijewardena that if a central bank makes continued losses, it could affect the independence of the Central Bank. In this regard, the Central Bank acknowledges the recent initiatives of the Government to ensure its independence.

7.Cherry-picking from the PRWpaper

Referring to the 2013 paper by Anil Perera, Deborah Ralston and J. Wickramanayake (PRW), Wijewardena states that, “having used the data relating to selected advanced and emerging countries that include Sri Lanka as well, they have found a significant and robust negative relationship between central bank financial strength and inflation. What it means is that if the balance sheet of a central bank is strong enough with high internal reserves, that central bank is in a stronger position to conduct its monetary policy effectively and push inflation down.”

In generalising the findings of PRW, Wijewardena ignores where the Central Bank of Sri Lanka is placed in the indicators used in the study. In terms of central bank independence as well as central bank financial strength, Sri Lanka has been classified in the “low” category in this study that covers the period from 1996-2008. In addition, PRW’s warning that “the conclusions of this study rely on a selected group of countries and hence, its result may not be generalised in the context of different economic and financial conditions” is disregarded. This warning seems to hold in spite of the fact that Sri Lankan data from 1996-2008has been included in the study. Moreover, Wijewardena’s summary of the PRW study displays a gross misrepresentation of the concept of causation, particularly as actual inflation outcomes are not given due consideration by Wijewardena in his two articles.

8. Recent steps to increase risk management

Wijewardena has appreciated the Central Bank’s assurance to the general public that its risk management is being strengthened continuously. Many points Wijewardena has highlighted in his recent articles have already been analysed in detail under the guidance of the Monetary Board, and steps are being taken to address potential weaknesses, if any. The establishment of a Risk Management Department and the steps taken to set up a Legal and Compliance Department at the Central Bank provide a stronger administrative framework to facilitate such analyses and improvements.