Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 15 July 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ruki Fernando, Marisa de Silva and Swasthika Arulingam

The people of Kepapulavu decided this week (11) to restart their fast unto death on 19 July, as they have lost all confidence in Government authorities, and the false promises given to them by the Chief Minister of the Northern Province C.V. Vigneswaran in March, this year.

The people called off their previous fast unto death on 24 March, upon the Chief Minister’s promise to look into the matter and provide them with a solution within three months. Three-and-a-half months since then, villagers are still awaiting the new Government to release their lands, under the occupation of the military since the end of the war in 2009.

In May this year, villagers were able to get a glimpse of their houses when the Army opened roads for limited time during an annual temple festival.

“Every year more and more changes are done to our lands. Some houses have been destroyed. The wells have been closed. Other buildings have been put up. Boundaries have been demarcated differently. But the jack and coconut trees which we have planted have started bearing fruits,” says Santhraleela, a community activist, upon seeing her old village.

However she is determined that all the villagers should be allowed to go back home. “They will have to release our lands. We will return. Even if they have destroyed our houses, we want them to release our lands,” says Santhraleela.

History

“When I enter my home, it feels as fondly familiar to me as the love of my mother and father…” – a village elder from Kepapulavu who is longing to return home.

The Kepapulavu Grama Niladhari division is situated in the Martinepattu Divisional Secretariat in Mullaitivu district. It comprises of four villages – Sooripuram, Seeniyamottai Kepapulavu, and Palakudiyiruppu. Some inhabitants who are mainly farmers and fishermen told us they trace their history for more than six decades while others were reported as landless families settled by the LTTE. Kepapulavu is known for its fertile red soil, fresh water wells, and marine resources.

The villagers were amongst the hundreds thousands displaced during the last phase of the war in 2009 and illegally detained in Menik farm.

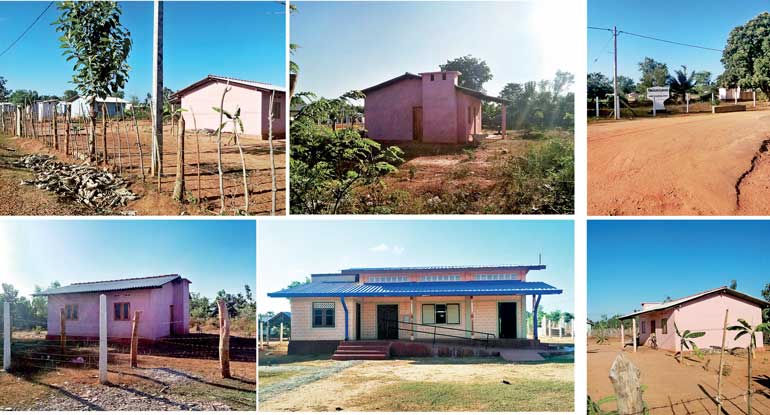

Despite appeals to go back to their own homes, in September 2012, around 150 families were allocated quarter acre of new lands to each, irrespective of how much they owned before displacement. They were thus re-displaced, to an area originally known as Sooripuram situated adjacent to their original villages. This is now called the ‘Kepapulavu Model Village’. People said they felt as if in the middle of nowhere. With no assistance to put up shelters by authorities, people on their own constructed shacks with scrap material they brought in from Menik farm.

The 150 families were requested to sign an application accepting their new lands by the former Government Agent of Mullaitivu. Although two of the 150 families refused to sign the document, they too were compelled to stay in the alternative plot of land and subsequently received a temporary permits. Around 146 other families had stayed with host families and relations and settled in Sooripuram in January 2013. They were not asked to sign any land permits upon their arrival. A total of 59 families from Sooripuram, 55 families from Pilavu Kudiviruppu and 159 families from Kepapulavu are currently displaced, due to the military occupation of their lands. The displaced families now reside in the Kepapulavu model village. In March 2013, 16 families were allowed to return to their original lands in Seeniyamottai.

The land which was once theirs

The housing lands of these displaced occupied by the military spans about 520 acres. Homes of people are now being used for settlements of military personnel and their families. In addition to the houses, school and church premises already in place, many pre-fabricated houses too have been installed within the settlement to accommodate military families.

In March 2014, the military had built and handed over 287 temporary houses for the people whose lands and buildings they had occupied1. When the former Deputy Minister of the Resettlement Ministry Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan inaugurated this housing scheme in 2013, he was reported to have told the people not to plant any trees, as it was only temporary housing.

Further, in 2014, when the Commanding Officer of the area had handed over the houses to the people, he too had told the people that these were only temporary lands and that if the political situation changes, that they would get their lands back.

Around 25-30 families do not live in the military built houses as there is inadequate water in that area. “We had large wells brimming with cool, clear water. We could bend over, and scoop water in a jug to quench our thirst. Now we have to walk long distances with buckets to collect water to have a bath,” reminisced village elders, who seem to be suffering the most, with vivid memories of home.

Farming families struggle to cultivate their lands as they have to walk seven to 10 km from the new settlement to reach their paddy lands, which was nearby their houses in their original villages. Cultivation and home gardening used to be family activities, but now, with the increase in distance, often women and children stay behind to look after the house.

“Around 3½ km stretch of beach is occupied by the military, that we are not permitted to use,” said Kaliappan Maheswaran, President of the Fisheries Society. The fishermen cannot dock their boats in this stretch of the coast. Fishing or throwing of nets is prohibited in 50ms of sea area touching the occupied coast. He states that prior to displacement the coast was around 150ms from their houses. Now fishermen have to cross 700ms in order to reach the sea.

Due to these barriers, fisher-folk go to sea only once in two or three days. Hence their income too have shrunk. Maheswaran also said that he used to cultivate peanuts so that even when it was off season for fishing, he would have a steady income coming in. However now he says this is not possible as water is only available in the common wells in the model village.

Due to change of lifestyle and lack of employment opportunities the villagers state the youth have become restless. People brew and drink illegal liquor. Police carry out regular crack downs, but as the fines are very low, the brewers merely pay off the fine and revert to their activities the very next day.

Women have taken on some of the income burden of their families. Young women leave to Colombo to work in garment factories and others travel far to find work. Women coming home late in to the night is creating frictions within families. Two women have joined the military as well.

Protests/appeals

The families of Kepapulavu had held at least five protests between 2012 and 2016 demanding that their lands be released. In the course of 2015, the people had also met with the Resettlement Minister, D.M. Swaminathan and Minister of Industry and Commerce, Rishad Bathiudeen regarding their demand to return to their places of origin. They have also written an appeal to the Presidential Secretariat and sent a letter to the then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, along with copies of 60 land deeds.

A single mother of two is the only remaining Plaintiff who continues a legal battle to win back her land, though three others had initially filed cases to reclaim land. She doesn’t live in the temporary house provided as she feels unsafe. She says she has thus far persisted in her Court case amidst intimidation, threats and even, on occasion, verbal abuse and degrading treatment by the then Area Commander Samarasinghe.

According to her, the five acres she owns include both paddy and housing lands. “The military has built a bakery, kitchen, hospital and two wells on my land. I was told that whenever senior Army officers visit, they are put up at accommodation on my land,” she said.

When the Courts and the Divisional Secretariat had asked her to accept alternative land, she had insisted on getting her own land back. “If only more people had filed cases, we could have been stronger and more effective. I also haven’t attended any more meetings with Government officials, as I’m very angry,” she added defiantly.

With all their previous attempts to get back their lands having failed, the people resorted to a fast on to death on 24 March. Santhraleela, a community leader who has been actively campaigning for her people, states that representatives from political parties inquired into their situation during this protest which lasted for three days.

On the third day the Chief Minister (CM) of the Northern Provincial Council via a letter had promised to look in to the matter and provide a solution within three months. Upon this promise, the fast was terminated. Three weeks after the fast, a team of five people were dispatched by the CM. Santhraleela says they asked general questions about their situation, but no undertaking was given to them about getting back their land. However, the three-month period has long past, and the villagers are yet to hear from the Chief Minister regarding a solution to their problem.

Struggles to reclaim lands

Coincidently in the month of March this year, after several years of protests and court battles, the people of Panama in the south eastern coast forcibly entered and reclaimed their lands, which had been occupied by the Navy, Air Force and Special Task Force since 2010. Communities across the country are continuing their struggle to reclaim lands which have been unfairly and illegally grabbed from them in the name of security and development. The new Government has taken the initiative to return a few of the illegally-occupied lands, but will they respond positively and allow all the displaced to go back home?

Footnotes

1 Ministry of Defence – Sri Lanka, Army completes construction of houses in Keppapilavu Model Village - http://www.defence.lk/new.asp?fname=Army_completes_construction_of_houses_in_Keppapilavu_Model_Village_20160303_04

(This article was originally written for WATCHDOG).