Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Saturday, 21 December 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Manoj Thibbotuwawa, Priyanka Jayawardena and Nisha Arunatilake

Tea is one of Sri Lanka’s major export commodities; it sustains the livelihoods of the majority of the estate population in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, it contributes 10% to the agricultural gross domestic product and 12% to the value of total exports of the country.

Despite the sector’s prominence, however, the benefits have not trickled down to the estate sector population. This is mainly due to the welfare of the plantation sector being neglected since colonial times. It is apparent in the high poverty rates (8.8% compared to 4.3% rural and 1.9% urban) and the prevalence of malnutrition (30% underweight and 32% stunting) among the estate population.

The long-standing discourse that tea pickers in Sri Lanka are underpaid and remain in poverty for generations came to light during the recent presidential elections as well. Since Sri Lanka’s plantation workers were already granted a pay hike in January 2019, under the two-year Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) between Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) and trade unions, it is uncertain if wages can be further increased.

In such an uncertain policy environment, this blog examines the possibility and the means of increasing the workers’ pay.

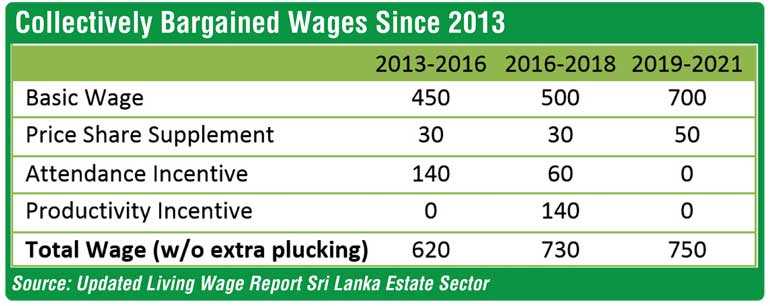

Under the CBA of 2016-18, workers received a daily wage of Rs. 730, which consisted of a basic wage (Rs.500/day), a price share supplement (Rs. 30/day), an attendance allowance (Rs. 60/day), and a productivity incentive (Rs. 140/day). Also, the tea pluckers who achieve a daily target of 18 kg of plucking were entitled to an over kilo payment of Rs. 25/kg for each additional kilogram of plucked raw leaf.

The common in-kind benefits workers receive include access to a medical clinic, maintenance of estate housing, provision of water to the estate houses, crèche, and tea rations – although not all tea estates provide these.

Thanks to the workers’ continuous struggle for Rs. 1,000 basic daily wage, the latest revision raised the workers’ base daily wage up to Rs. 700. The Price Share Supplement (PSS) payment too increased up to Rs. 50. However, worker unions allege that the RPCs deprive the tea workers of the attendance allowance and the productivity incentives, limiting the gross pay hike to a mere Rs. 20.

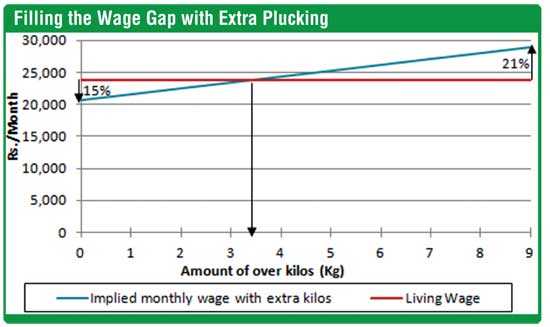

On the other hand, the Planters’ Association argues that workers can earn even more than the demanded Rs. 1,000 with the increased over kilo payment (Rs. 40/Kg), aimed at improving labour productivity.

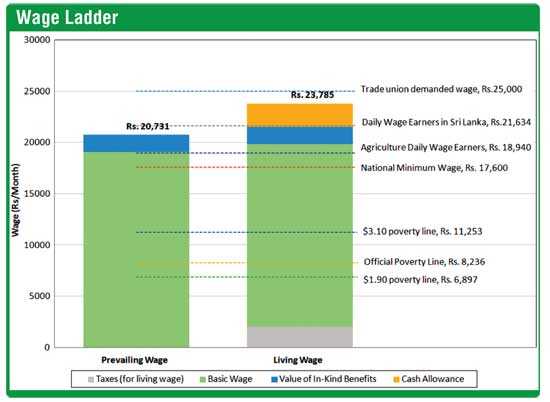

It further emphasises that Sri Lanka’s major competitors such as Kenya, South India, and Assam reach much higher labour productivity levels, ranging from 36 kg/day to 60 kg/day, with a daily minimum target of 24kg-40 kg. Under the current wage structure, implied monthly wage of tea pluckers (including common in-kind benefits) amounts to Rs. 20,731, without any additional plucking over the daily target.

The Global Living Wage Coalition (GLWC) states that workers should receive a remuneration that can provide a decent standard of living for the worker and their family. In Sri Lanka, the essential elements of a living wage that include food, water, housing, education, healthcare, and transportation are below the required levels, and whether the plantation workers receive a  living wage is highly questionable.

living wage is highly questionable.

A study by IPS and GLWC examined the living wage for tea pluckers in Sri Lanka, to act as a catalyst for action throughout the value chain to raise wages towards a living wage. Here, the estimated gross living wage was Rs. 23,785 per month in January 2019.

Estimated living and prevailing wages are considerably higher than most of the currently available benchmarks (national minimum wage and agriculture daily wage earners income) and poverty lines (National Official Poverty Line, World Bank $3.1, and $1.9 poverty lines). Also, the prevailing wage is slightly below the average income received by daily wage earners at the national level.

While the trade unions have demanded a slightly higher wage than the estimated living wage, this analysis finds that the prevailing wage has to be raised by at least Rs. 3,055 (15%) to reach the living wage level.

Low labour productivity, coupled with the high cost of production, which exerts enormous pressure on dwindling auction prices, has a grave impact on bridging the wage gap, as well as the overall viability of the tea sector. While the study finds, the workers who pluck around 3.5kg per day over the daily target earn more than the living wage, the amount of over kilo bonus payment the workers receive can vary significantly due to temporal, seasonal, and factory-related variations in the daily kilo threshold target, as well as individual plucking differences. For example, certain estates have reported on average nine over kilos per day, which would earn the workers 21% more than the living wage, whereas IPS/GLWC study estimated only 2.25 over kilos per day.

Therefore, plucking 3.5 over kilos every day, which is almost 20% more than the daily threshold, to earn a living wage for over 100,000 tea pluckers will be quite challenging. Even  according to the RPC sources, a majority of the workforce works only for 20-25 hours per week, with an effective plucking time of only 40% of the working time, due to physical and psychological conditions; thus, they reach a low plucking average of only 16-18kg.

according to the RPC sources, a majority of the workforce works only for 20-25 hours per week, with an effective plucking time of only 40% of the working time, due to physical and psychological conditions; thus, they reach a low plucking average of only 16-18kg.

Even though there have been significant improvements over the years, the estate sector has continued to lag behind the rest of the country in different measures of development. Low wages are partly responsible for this situation. The above analysis shows that, on average, the estate sector wages at present are below the living wage standard, even if the workers earn a relatively higher wage than certain wage and poverty benchmarks

Even though further increases in wages may not be possible with the current wage model, which offers a mandatory 300 days of work per year at a lower level of labour productivity, it allows efficient producers who are able to pluck sufficient extra kilos to earn either a living wage or the trade union demanded wage.

However, in the long run, the tea sector needs a sustainable productivity-based, revenue-sharing model where the workers can maximise their earnings with a sense of ownership for the land. This strategy has proven successful in the tea smallholder sector, as well as in certain high producing competitive countries.

[Manoj Thibbotuwawa is a Research Fellow, Priyanka Jayawardena is a Research Economist, and Nisha Arunatilake is Director of Research at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]