Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 25 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Vinod Moonesinghe

By Vinod Moonesinghe

One should have thought that Elmo de Silva (‘The pre-1977 closed economy: Lest we forget,’ Daily FT, 9 September), as a middle-level civil servant in the 1970s, would have been able to give us an objective insight into the workings of the pre-1977 economy. Unfortunately, he offers, instead, a subjective and unscientific view, out of its historical and socio-economic contexts.

A truly objective and scientific discussion should place the economic regime of that period in its historical context, avoiding over-reliance on anecdotes, and preferring a holistic overview of its effects.

The term “closed economy” is an emotive creation of neo-liberal propagandists, placed by then in opposition to the so-called “open economy”. Yet even the most rabid of neo-liberals must acknowledge that the regulated economy originated in Europe during the First World War, when governments realised the necessity for central control of the economy, to maximise their resources – so-called “War Socialism”. During the Second World War, Britain developed a regulated economy which proved able to out-produce Hitler’s Nazi empire.

On the other hand, the colonial Sri Lankan economy provided a good example of the “open economy”, allowing the British to exploit Sri Lanka’s resources at will. Existing industries, for example the cotton-growing/weaving industry of the northern areas were destroyed deliberately to make way for Manchester’s exports.

The colonial Government destroyed the traditional, eco-friendly paddy/dry-land/chena agricultural and associated irrigation systems, and created a pattern of rural indebtedness and usurious surplus extraction. A backward colonial plantation system, based on West Indian slave methods, provided over 90% of exports, which paid for imports of food and other consumption goods.

During the Second World War, fear of an invasion or uprising caused the British colonial government to implement changes. It set up a food rationing system, based on the British ration-book system (which de Silva appears to think was a result of the post 1956-period State-directed economy), to feed which increased rice imports and production (complete with rice-barricades, or haalpolu) became necessary. Incentives were given for local industry, but there were no takers: the State had to step in and establish factories.

The first post-colonial regime continued with the colonial set-up, with the exception that it closed down many of the wartime industries. High prices for tea, rubber and coconut enabled high expenditure on consumer goods. This caused an acute shortage of foreign exchange, once the reserves built up over many years were dissipated in the course of the post-1948 honeymoon.

On top of this, the estate owners, sensing the end of the Planter Raj, began disinvesting into East Africa – where they had no fear of human rights or trade unions — and cut down on replanting, affecting future yields.

The shortage of foreign exchange came, de Silva leads us to assume, as a direct result of the economic regime of 1956-77. However, that would be putting the cart before the horse. The shortage of foreign exchange came about because of the profligate and unproductive spending which characterised the pre-1956 economic regime.

The reserves accumulated during the Korean War Boom were dissipated within a period of years. The stiff foreign exchange controls, the import restrictions, the lack of adequate foreign exchange on import permits, and the restrictions on foreign travel of the post-1956 era, of which de Silva complains, came about because of this shortage of foreign exchange.

The economic regime begun in 1956 bore a great resemblance to the State-directed economic policies which caused the rapid growth of the economies of South Korea and Taiwan. However, Sri Lanka lacked many of the factors which helped accelerate their growth.

Firstly, the country lacked the deep-going land reforms of South Korea and Taiwan – which drastically improved productivity and created large internal markets for manufactured goods. We had no land reform until 1972 – although the Paddy lands Act went a long way towards increasing farmer incomes – and when it came, the ceiling on land was a very high 25 acres (10 ha), compared to 7.5 acres (3 ha) in South Korea and Taiwan. The average paddy smallholding being only a quarter acre in size, there could be no advance in productivity over mere subsistence.

Secondly, the State was “burdened” with the free rice ration, causing huge outflows of foreign exchange, which none of the East Asian economies needed to bear. Thirdly, Sri Lanka was a functioning democracy: unlike here, East Asian workers were denied trade union and other rights, enabling wages to be kept low, and the absence of democracy also ensured continuity. In Sri Lanka the alternation of governments meant there could not be real continuity, and the country lacked a truly coherent plan for industrialisation.

Lastly, and probably most importantly, Sri Lanka did not lie on the USA’s front line with China and the USSR: this was a huge advantage for the Asian Tigers, which were provided enormous funds for investment, as well as access to the huge US market.

On the other hand, Sri Lanka was kept isolated by the West, with little access to markets or funds for investment, so industrialisation had to take place ad-hoc, responding to specific immediate needs. For example, phases 2 and 3 of the Oruwela Steel mill, involving steel production using our own iron ore, never came to fruition.

Most of the problems which de Silva mentions, came about because of the shortage of foreign exchange, exacerbated by the peculiar circumstances of the mid-70s. The OPEC oil embargo of 1973-74 caused a huge leap in petroleum prices, which impacted the country negatively and came on top of a three-year drought which devastated the agricultural sector, at a time when the entire world went through horrendous food shortages, even the mighty USA being affected. These circumstances deepened the crisis the country faced on account of low prices for tea and due to 40% of tea plants being unproductive, because the tea companies had reduced replanting– which forced the nationalisation of plantations, a little too late (the fruits of the tea-replanting program set up by Plantation Industries Minister Dr. Colvin R. de Silva, were only garnered by the post-1977 regime).

This situation was compounded by non-cooperation or even outright sabotage by the West, especially after the petroleum companies were nationalised. De Silva virtually admits as much when he writes that “With the scarcity of forex the Govt. resorted to lines of credit but aid for imports was not forthcoming.”

This lack of credit owed nothing to any lack of credit-worthiness on Sri Lanka’s part – the country was known to repay debts promptly. Sri Lanka’s blacklisting had a political motivation. Industrialisation efforts were also sabotaged or stymied. For example, efforts to manufacture essential sulpha drugs were obstructed.

Nevertheless, the results of Sri Lanka’s State-directed economic policy were impressive. For example, manufacturing, which was only 5% of gross domestic product in 1955, rose to 23% of GDP by 1977. The mixed economic policy kept most of heavy industry (in which the bourgeoisie were unwilling to invest) in State hands, but most light industry remained under private or co-operative ownership. Sri Lanka’s PVC products industry arose as a result of this policy.

The most impressive results came in the machinery sector: Sri Lanka became a significant manufacturer of plant and machinery, particularly for tea and rubber factories, exporting all over the world. The State-manufactured machine tools and transport equipment: the CGR built shunting locomotives and the CTB even made its own machinery for manufacturing bus chassis. In the private sector, there were three firms manufacturing refrigerators, two making motor vehicle radiators, and several manufacturing electronic equipment.

Considerable innovation also took place. Sri Lanka originated three inventions which gained a hold worldwide: the fluidised-bed tea drier, the rain-cover for rubber tapping and the solar adsorption refrigerator.

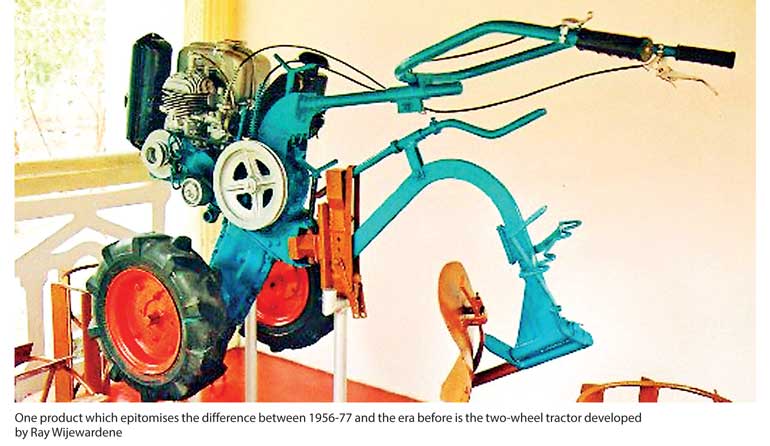

One product, which epitomises the difference between 1956-77 and the era before, is the two-wheel tractor. When Ray Wijewardene developed his prototype in 1955, he had to licence production to the Landmaster Company in England. The first two-wheeled tractor to be made in Sri Lanka came off the production line in 1975. A study done in the late 1960s of nuclear proliferation included Sri Lanka among the few countries thought to possess the capability to make the bomb.

Significantly, de Silva refers to an “erroneous belief” that this country “could produce all its consumables and raw material requirements and even some types of machinery”. At least an effort took place to fulfil such a belief, infinitely better than the current situation, in which we have a garment-manufacturing sector, yet do not produce even the needles required by Juki machines.

Certainly, there were many improvements which could have been done, much better bottom-up planning, and better implementation. However, overall, that the 1956-77regime was not sustained can be attributed to the fact that, unlike South Korea or Taiwan, this country was relatively democratic. Following the election of the UNP on a promise of increasing people’s food rations (the so-called “eta ata”), a policy of unbridled imports began.

The post-1977 era saw the rapid de-industrialisation of the country. Between 1977 and 1983, manufacturing fell from 23% of GDP to 14% – the “Open Economy” ensuring that it never rose above 19% since. Even worse, key sectors, such as electronics and tea machinery, collapsed in the face of unbridled foreign competition. An estimate from the mid-1980s gave job-loss figures resulting from factory closures in excess of 100,000.The country was left with export-processing, mainly garments.

Virtually the entire economic “growth” of the post-1977 period can be attributed to the fact that the OPEC oil embargo resulted in high petroleum prices, which, although affecting the Sri Lankan economy badly in 1974-77, led to rapid growth of the Middle-Eastern economies. This in turn led to (a) a reversal of the downward trend of tea prices and (b) opening up the Middle-Eastern labour market to Sri Lankans after 1976. The latter, in particular, provided remittances which kept economy afloat and, despite the post-1977 unequal-income regime, resulted in housemaids’ money improving their poor households’ economic status. Foreign remittances are now the mainstay of the Sri Lankan economy.

Had the State-directed economy continued after 1977, with its manufacturing sector still intact, free from competition from cheap imports, the country would have been able to provide locally-manufactured consumer items to the burgeoning internal market caused by the tea price and Middle-Eastern employment windfalls. The base would have been laid for industrialisation, and today we should have been in the economic situation of Taiwan a quarter century ago.

One issue on which de Silva is severely mistaken is that of the rational drugs policy instituted as a consequence of the Bibile-Wickremasinghe report. De Silva says, without a jot of proof, that drugs from “communist countries” were imported which were “inferior in quality”. He probably doesn’t realise that Sri Lanka’s rational drugs policy was accepted as the international benchmark, and has been copied by several countries. Bibile himself went on to be an adviser on rational drug policy to the World Health Organisation.

Of course, not all public servants were on the level of a Bibile, or a GVS de Silva (who drew up the Paddy Lands Act). Many top civil servants were imbued with the ideas of the colonial compradore class, and had no conception of what was required for industrialisation. Elmo de Silva himself seems to number among them.

He complains that the “Gekko” brand mammotties manufactured by the Hardware Corporation were not of as good quality as the British-made ones, or that locally-produced safety blades did not shave properly. Of course they were not of as high quality as British products, but then, neither were “Japanese goods” of high quality in the post-war period. It took decades to develop the high degree of quality seen today in Japan, and this was only possible because Japan had a “closed economy”. Does de Silva think that Sri Lanka should not have ventured into manufacturing agricultural implements, when the economy was based on agriculture?

He is guilty of a misapprehension when he says that the products of the Ceramics Corporation were of low quality. What he means is that they were not luxury fittings, which is not the same thing, and they were perfectly adequate for the needs of most ordinary mortals.

De Silva’s complaints are mainly about problems faced by the top 5% of people in this country at the time – for example the shortages of butter, the inability to import a car, the inability to travel overseas, the shortage of toilet paper, or having to go to a hospital and wait one’s turn like an ordinary person. It is precisely this elitist attitude which any democratic government has to fight, to enable a level playing field for all its citizens.