Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 6 November 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

CNN: Observers in Beijing and Delhi are watching events in Sri Lanka closely to see what the country’s constitutional crisis means for a bigger contest: the race for influence in the Indian Ocean region.

Political turmoil in the island nation was triggered late on 26 October when President Maithripala Sirisena appointed his predecessor Mahinda Rajapaksa as Prime Minister, after summarily firing the incumbent, Ranil Wickremesinghe, who insists he’s still in charge. The two are now set to face off in Parliament in a confidence vote.

“The move caught me and most observers here in Washington and even (the Sri Lankan capital) Colombo by surprise,” said Jeff Smith, a fellow at the DC-based Heritage Foundation think tank.

Sirisena came to power in 2015 with Wickremesinghe’s support after breaking away from Rajapaksa, who was accused by rights groups of increasingly authoritarian behaviour during his time as president between 2005 and 2015, especially during the final years of a brutal civil war that ended in May 2009.

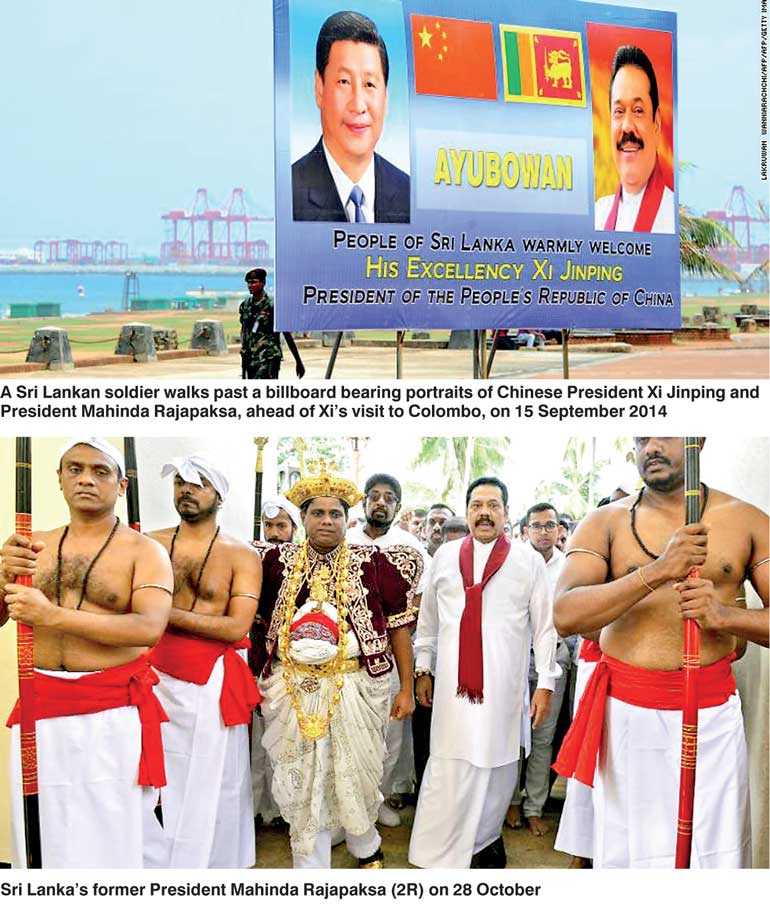

Rajapaksa’s reign had also seen an influx of Chinese investment in Sri Lanka: between 2005 and 2014, Beijing investments and contracts totalled more than $15 billion, according to the American Enterprise Institute, raising eyebrows in Washington and its ally New Delhi.

Chinese investments paid for a new port on Sri Lanka’s southern coast, a new airport and new railway, among other projects that saddled Colombo with a multi-billion dollar mountain of debt. Alarm bells also went off in 2014, when Chinese a submarine docked in Colombo.

New era

Rajapaksa’s ouster raised hopes for democracy and an improvement in human rights in Sri Lanka.

For many in the US and India, it was also seen as an opportunity to counter Chinese influence in New Delhi’s backyard, with the new Sirisena-Wickremesinghe Government coming to power “pledging to revisit and revise some of the deals Rajapaksa had signed with China,” said Smith.

“It ultimately found itself in a compromised economic position and forced to renegotiate rather than cancel some of the contracts,” he explained.

Struggling to service its debts, in 2017 Sri Lanka moved to lease the Chinese-funded port in the south – to Chinese State-owned firms.

Still, in recent years Colombo also “did a good job assuaging some of India’s concerns about Chinese activity in Sri Lanka and ... really significantly improving cooperation with the US over the last few years,” said Smith.

According to Smith, some elements of cooperation had been halted or limited during Rajapaksa’s term over concerns of human rights violations and the military’s conduct during the civil war.

“Some of those avenues... resumed or were upgraded after the new government came to power in 2015,” Smith said, highlighting progress on both the economic and military fronts, with a US aircraft carrier visiting Colombo in 2017.

Uncertain future

But with Sirisena now backing Rajapaksa again, the question is what happens now. Will China have the upper hand if Rajapaksa displaces Wickremesinghe?

It might not be so simple, according to Constantino Xavier of the Brookings Institution’s Indian arm.

“People quite superficially tend to portray Mahinda Rajapaksa in particular as a primitive, anti-India, pro-China person and conversely Ranil Wickremesinghe somehow as the leader of more pro-India factions,” said Xavier, pointing, as an example, to a recent visit to New Delhi by Rajapaksa.

“After burning some of his bridges with Delhi, (he is) being smart enough to rebuild them. His visit in September was part of that exercise,” said Xavier.

India was clearly concerned about the level of Chinese influence and activity during Rajapaksa’s last term in power. But it’s likely that China, with its financial muscle, is here to stay, no matter who is in power, in Sri Lanka or in the other small countries across the region, said Xavier.

“This applies to the Maldives, this applies to Nepal, this applies to Bangladesh and it applies to Sri Lanka,” said Xavier, adding that although some countries will continue to work with India, Chinese money means that cooperation is no exclusive.

“The Chinese are now and will be permanently involved economically in these countries. Because they have the financial power.”