Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Sunday Mar 01, 2026

Friday, 27 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Janaka Wijayasiri, Kithmina Hewage and Nuwanthi Senaratne

In an increasingly-globalised world, ease of trading across borders is essential for businesses. Many governments around the world have recognised this and are undertaking measures to increase countries’ participation and competitiveness in trade by simplifying trade and transport procedures and document requirements.

Along these lines, the Government of Sri Lanka has identified the implementation of a Single Window (SW) for trade as a national priority. Its implementation is expected to reduce the time and costs of cross-border trade, and enhance the country’s trade and competitiveness. Also, the establishment of SW will be an important step towards meeting the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement, which Sri Lanka has ratified.

Sri Lanka has indicated its intention of establishing a SW by 31 December 2022, while calling for technical assistance towards its implementation. However, it is yet to decide on its SW ambitions by defining the scope, which is currently under consideration. This article suggests that a little bit of walking before running would ensure a successful phase-wise implementation of SW.

A SW allows traders to submit trade information in a virtual location that communicates with the relevant Government Agencies (GAs) and obtain Certificates, Permits, Licenses (CPLs), and approvals electronically. With a SW facility, traders no longer need to visit different physical locations to obtain them.

Many countries have already undertaken steps to switch from paper-based customs processes towards a paperless system. Electronic systems for exchanging regulatory information have become an important means of managing cross-border trade. Some economies have gone a step further by linking not only traders and customs but also other GAs involved in trade, through the SW. The most advanced systems in South Korea and Singapore connect banks, customs brokers, insurance companies, and freight forwarders.

If implemented effectively, a SW can significantly reduce the time, money, and documents required for trading. It can benefit not only the traders but the government and the economy. Several economies have reported positive gains from SW implementation; for example, the introduction of a SW in South Korea in 2010 generated some $ 18 million benefits to the economy.

Similarly, the SW in Singapore brought together more than 35 GAs since 1989, resulting in huge productivity gains for the government. However, there are many challenges to its establishment, which go beyond technical issues.

Creating a SW requires tremendous effort, costs, changes in mindset, and most importantly, strong political will. For example, the initial budget of SW in Singapore was $ 14.3 million in 1988; since then it has evolved over almost three decades, with the latest upgrade expected to cost $75 million in 2017.

SWs are implemented in an incremental manner rather than in a big-bang approach. They gradually evolve over a long period of time, given that SW is an extremely complex and costly undertaking. As a result, there are different SWs with different scopes and functionalities across the world, reflecting the readiness and priorities of individual countries.

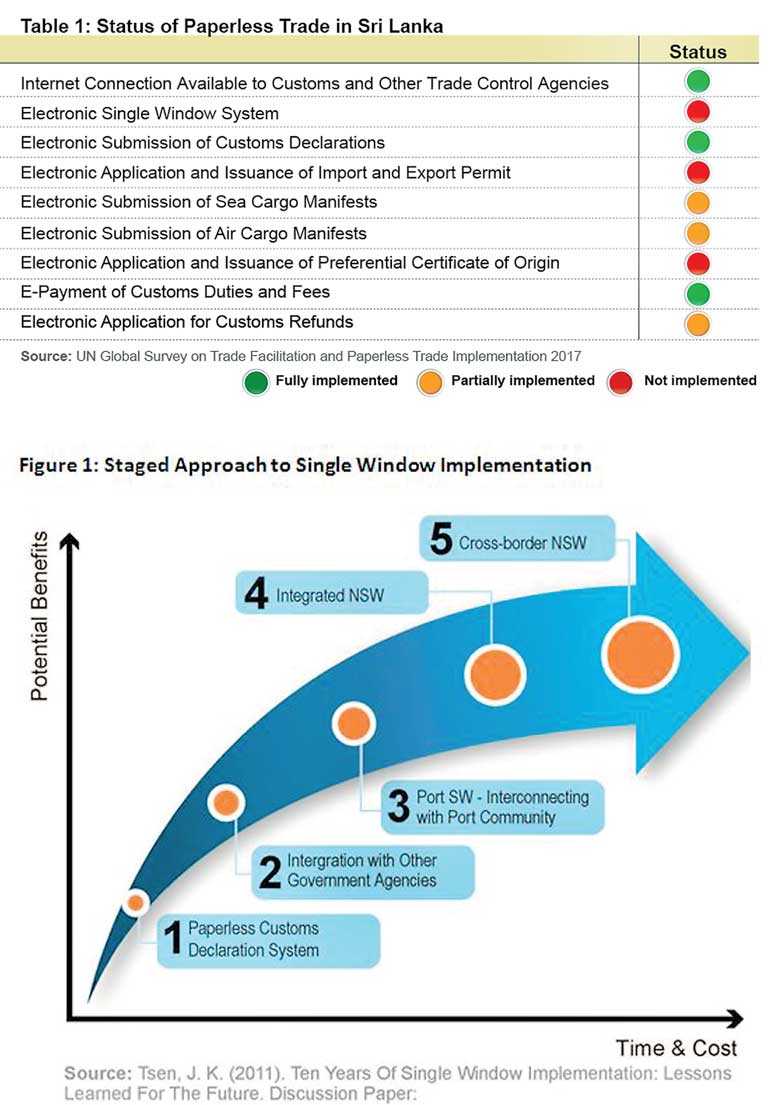

Broadly speaking, a SW can be divided into five incremental development levels, involving migration from paper to electronic-documents whilst integrating customs, other GAs and private stakeholders (Figure 1).

Most countries first start with electronic customs declaration systems because every import-export must be declared to customs. This usually evolves from a paper-based customs or from the use of traditional Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) systems, to which traders submit both electronic and paper declarations. In a paperless customs environment (Level 1), documents are sent electronically through secure Value Added Networks (VANs), without requiring physical visits and paper submissions.

After linking traders and customs electronically, countries can develop a regulatory SW (Level 2) by linking several or all GAs regulating trade. The system at this level allows for application and issuance of electronic CPLs by GAs. With such a system, traders do not need to make physical visits to different GAs. The most challenging feature of a regulatory SW is single submission, where traders submit their export or import data only once to obtain all necessary CPLs and customs declarations.

The next stage in developing a SW is integrating the private-sector stakeholders and intermediaries at major airports and seaports. A Port SW (Level 3) connects the port community to the electronic customs declaration system and other GAs. The system manages and automates port and logistics procedures through a single submission of data by connecting transport and logistics chains.

Fully Integrated SW (Level 4) connects not only traders, customs, and other GAs, but also private-sector participants such as banks, customs brokers, insurance companies, freight forwarders, and other logistics service providers.

Cross-border SW (Level 5) connects and integrates national SWs at bilateral/regional levels, allowing cross-border electronic-information exchange between economies within a regional grouping.

At present, Sri Lanka does not have a national SW (Table 1). The system in place is a customs centric facility, fulfilling traditional customs clearance functions. Sri Lanka Customs (SLC) is partially automated and connected to other GAs and ports electronically through ASYCUDAWorld, a computerised customs management system.

While the system implemented covers both imports and exports, it has not eliminated the need for paper handling; traders/agents can only electronically submit documents, data and make online payments of duties/fees to SLC through selected banks. However, they still have to visit SLC to submit physical paper documents because of signature, and to obtain approvals/clearance.

Last year an online payment platform was launched while digital signatures were accepted this year, but the uptake has been low by the trading community. Currently, SLC is ready to move to a completely paperless system with an accompanying digital signature. Of the 30 plus GAs that are involved in issuing CPLs, only a few are electronically and partially linked to SLC; the required documents still need to be submitted by traders/agents to these agencies for relaying of approvals to SLC. In addition to SLC, Sri Lanka Ports Authority and Sri Lanka Cargo have their own automated management systems which are connected to Customs through ASYCUDA.

Sri Lanka is at an early stage of SW development and currently, a blueprint is being prepared for its implementation which will spell out amongst others, the scope of the functions to be included.

Given Sri Lanka’s current situation – a paperless customs but not interconnected with other GAs with a lot of cumbersome procedures related to CPLs – a regulatory SW (Level 2) should be the country’s target with regard to SW development. Or, perhaps the extension of the SW to serve the entire trade and logistics community at the ports (Level 3) could be within the scope of SW development. Cross-border information exchange can also be included after the implementation of paperless customs.

However, it is important to bear in mind that, higher levels of SW development take time, money, and effort (Figure 1); thus it requires a careful cost-benefit analysis, as well as managing the expectations of all stakeholders given the time frame for implementation, capabilities and resources available in Sri Lanka.

(Janaka Wijayasiri is a Research Fellow, Kithmina Hewage is a Research Officer, and Nuwanthi Senaratne is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To share your comments with the authors, please write to [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. For more articles, visit our blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.)