Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 16 February 2021 00:57 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

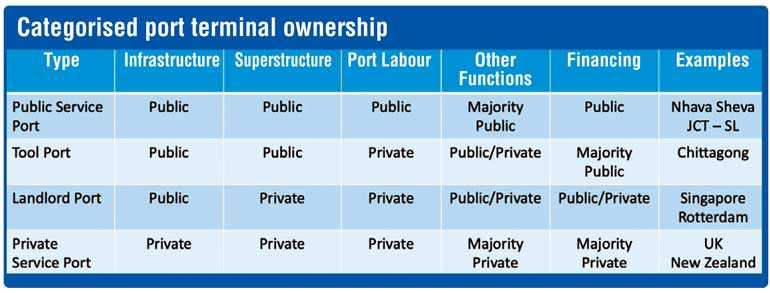

Private sector involvement in developing ports became a critical necessity in the 1980s due to a host of reasons. The bottleneck effect caused due to congestion in ports, had a considerable strain on the efficiency of distribution chains, which is an important factor that needed attention.

In this backdrop, government investments into port development were seen as a ‘White Elephant Syndrome’. Amplified by recurring port congestion, consequent chronic service failures, were mainly attributed to the deterioration of service quality during this period.

The World Bank has classified port terminal ownership and administration into four models based on public private partnership.

Opportunity of gaining a share in Indian subcontinent transhipment market in post-COVID recovery

Opportunity of gaining a share in Indian subcontinent transhipment market in post-COVID recovery

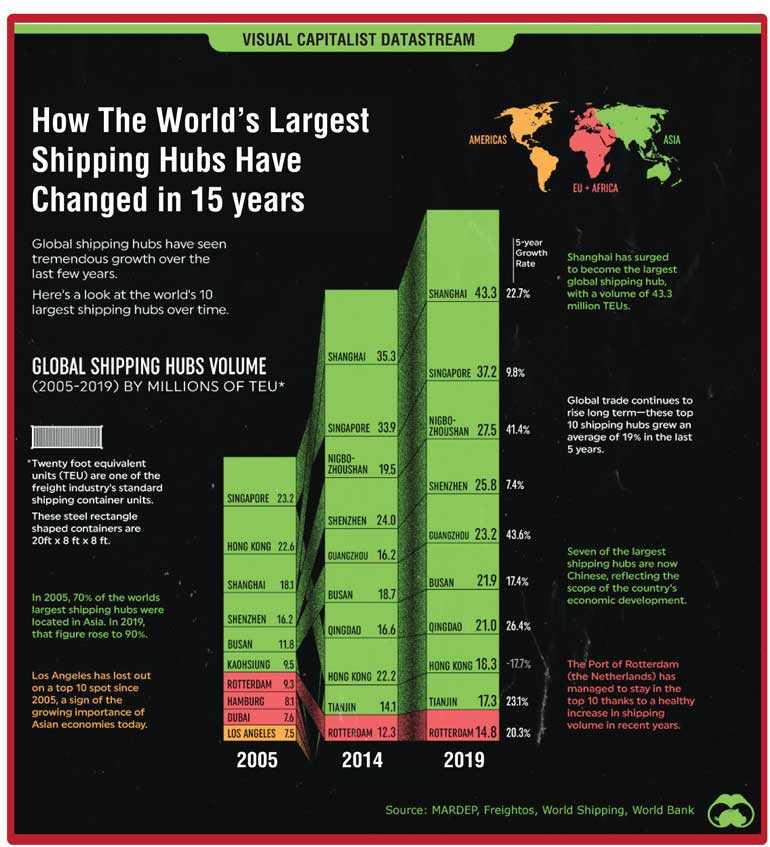

Transhipment emerged in the 1970s as trade with Asia increased. However, volumes were not sufficient to justify direct connections to many ports, in Asia. Nevertheless, Kaohsiung emerged as the first transhipment hub. As container ships grew larger on improved designs setting up of pure transhipment hubs along major shipping routes, including Colombo, became a necessity.

The Colombo Port expansion project was funded by the ADB owing to the country’s ailing domestic economy. In the ADB’s 2007 report, the rationale for the expansion is stated as “Colombo Port is the natural transhipment hub for the South Asian region. However, in recent years Colombo Port lost its market share in the regional transhipment market because the fundamentals of the market changed, and Colombo Port did not adapt. Colombo Port cannot offer the additional operating capacity required to compete for the Indian subcontinent transhipment market or the depth required to berth the latest generation container ships. Colombo Port will have to develop additional container berths with the required depth to address this capacity and depth infrastructure constraints if it is to remain a transhipment hub port.”

Transhipment and India’s contribution towards hub status of the Colombo Port is a fact that cannot be ignored.

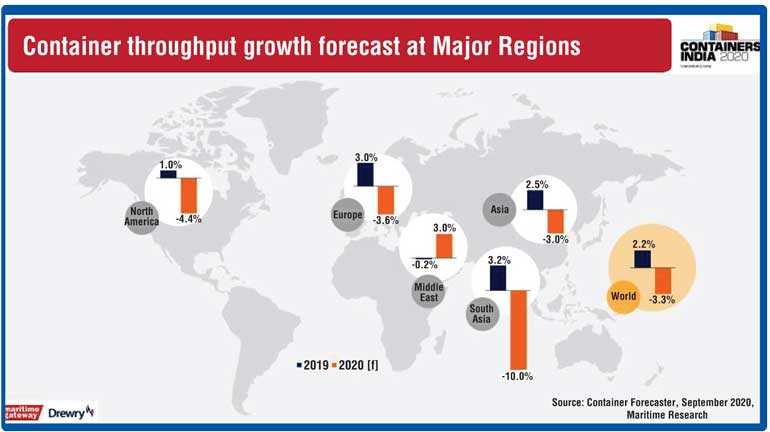

South Asia has suffered the most during the pandemic with a 10% dip in forecasted volumes. The region will play catch-up in the years to come.

Meanwhile, Singapore has lost its top slot to Shanghai in the last 14 years. Zhoushan, Shenzen and Guanzhou have been developed as very close competitors to Singapore. Growth in these new ports was driven by Chinese economic growth.

Similarly, Sri Lanka cannot ignore the growth in the Indian economy. IMF projected India to grow by 11.5% in 2021 and Sri Lanka is well positioned to benefit from this growth.

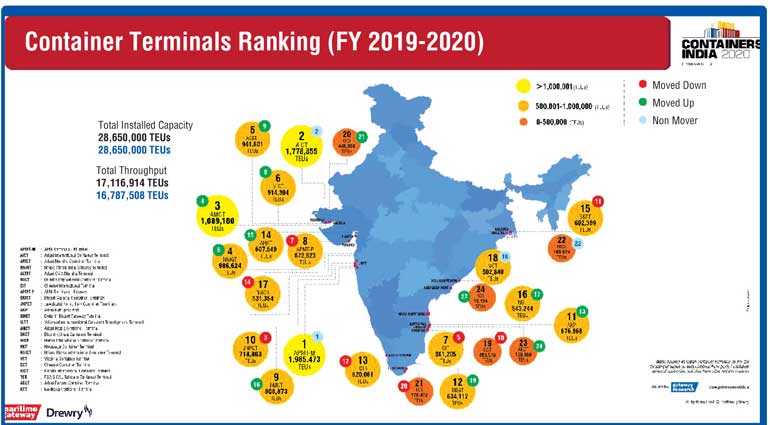

India has 12 major ports and around 200 non-major ports. In FY20, major ports in India handled 704.82 million metric tonnes (MMT) of cargo. Cargo traffic at non-major ports reached 447.21 MMT in FY20. Since ports handle almost 95% of the trade volumes in India, the rising trade has contributed significantly to the country’s cargo traffic. Given the positive outlook, proposed investment in major ports was expected to reach $ 18.6 billion by 2020, while those in non-major ports, around $ 28.5 billion.

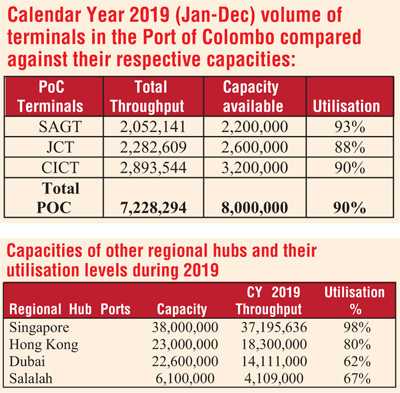

Indian transhipment is the main business of the Port of Colombo. With terminals being developed, the total capacity of Colombo can be projected to an estimated 14-15 m TEUs annually. As of now 85% of this will be transhipment containers, over 70% of which will be to/from India, hence Colombo cannot discount the relevance of India, to remain as a prospective hub port.

As explained initially, transhipment hubs were created as domestic economies were unable to sustain longer shipping routes. In this backdrop, what we need to realise is that expansion of the Colombo Port is unsustainable in the absence of Indian transhipment containers.

Fundamentals of port business – importance of links between port operators and shipping lines

Major port operators have established links with main shipping lines to plan routes, which are strategically important to shipping lines. The shipping lines schedule their routes considering the services and pricing offered by port operators.

This and a host of other reasons compel governments to refrain from ports development, including inability and lack of flexibility to attract main shipping lines. These are vital factors that Sri Lanka seems to have ignored in its decision to develop the East Container Terminal.

The top 10 terminal operators with their respective market shares in 2019

The Port of Colombo has reached its capacity and losing market share

As of 2018-2019 we have reached the maximum capacity levels and had failed to gain an annual increase of at least 5-6% of transhipment volume, undoubtedly lost to regional peers.

Shippers’ Academy Colombo CEO Rohan Masakorala in his article published in the Daily FT captioned ‘Shipping and ports in crisis,’ clearly articulates an opportunity cost of 10% growth in transhipment volume lost due to delays in developing the ECT.

ECT was to be operational by 2017 which would have added approx. 3 million TEUs annually to the POC capacity. Sri Lanka has lost a golden opportunity to capture market share due to inconsistent Government policy.

The Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) completed development of the first phase of ECT by early 2015. This consisted of a 600m length quay wall, part container yard and a 440m deep-water berth. In 2016 a request for a proposal was floated to develop ECT on a BOT basis. This was terminated in 2017 when the GOSL contracted with India and Japan to develop the ECT. Based on these discussions, a MOC was signed in May 2019. This was overturned in February 2021 to develop ECT as a public service port.

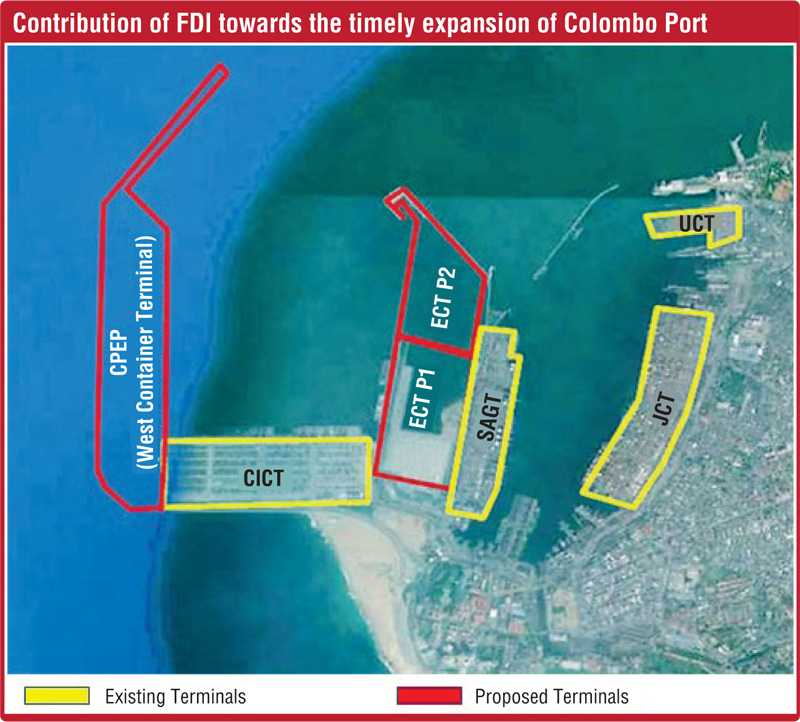

Contribution of FDI towards the timely expansion of the Colombo Port

Only 20% of the ECT has been developed up to now. It can service only 200,000 TEUs annually at its best now. An investment of another $ 550 million is required to develop the ECT to handle three million TEUs annually. This needs to be done immediately to develop the terminal within two years.

Duration is crucial in maintaining market share for the entire port. FDI is the need of the hour. It brings a package of capital and also market access and technology transfer will ensure timely development without stressing the GOSL financially.

The GOSL will find it very challenging to invest $ 550 m to develop ECT based on its financial capability. Only time will tell if the decision to develop ECT as a public service port would be implemented in a timely and cost-effective manner, as articulated by the trade unions.

On a positive note, the GOSL’s initiative to hold discussions with India and Japan to develop the Western Container Terminal (WCT) as a private service port on a 35-year concession is a welcome change under these circumstances.

(The full length Pathfinder Brief is available at www.pathfinderfoundation.org. Readers’ comments welcome to [email protected])