Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 4 September 2018 00:19 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

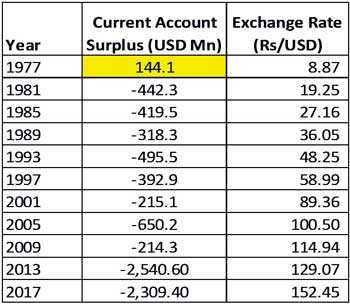

As the rupee hit a new all-time low of 161 against the dollar, the main reason for the continuous depreciation of the rupee over the last four decades (from a mere Rs 9 per dollar) was also disclosed elsewhere. Trade data for 2018 up to June was released.

Deficit in external current account

key reason for rupee’s slide

While the exports have increased by 6% to $ 5,732 million in the first half of 2018, the imports have increased by 13% to $ 11,441 million, resulting in a 20% increase in trade deficit to $ 5,709 million, which is almost as high as the total export value!

1977 was the last year Sri Lanka recorded a surplus in its external current account. Since then, it has always been in deficit. What it means is that all our external earnings - not just exports, but worker remittances and tourism earnings - are not sufficient to bear the import bill. Clearly that has the most profound depreciating impact on the rupee, in addition to swelling the foreign borrowings, as we have to resort to borrowings to finance the imports.

Rupee stability due to financial flows is temporary

While the rupee would have been relatively stable in certain short periods in the past, it was predominantly due to temporary financial inflows. For example, at times when foreign investments in domestic treasury bonds or equities were taking place, the rupee could have been more stable or may have even appreciated.

However logic as well as history indicates that dependence on financial inflows is not sustainable and such inflows could reverse to outflows at the blink of an eye. Therefore, in the long run, the exchange rate is firmly determined by the performance of the external current account.

Where did we make the mistake?

Clearly the statistics indicate that the opening up of the economy has led to an inflow of imports, although the exports have not taken off in the same speed. As trade liberalisation is being promoted today, it is essential that the outcome of the liberalisation in 1977 is analysed and well understood.

One could argue that the opening up of the economy in 1977 was not carried out carefully, and failed to propel the following two aspects, which resulted in an escalating trade deficit and resultantly an ever-weakening rupee.

Failing to advance in global value chain

To this date, Sri Lanka is predominantly stuck in traditional exports, such as apparel and tea, and has not progressed in the global value chain. The collective contribution of apparel and tea to total exports has remained around 60% from 2000 to 2017. Had we advanced in the global value chain, the percentage contribution from traditional sectors should have gradually contracted towards 50% or even 40%.

In comparison in the case of South Korea, clothing exports as a percentage of total exports reduced from 34% in 1970 to 22% by 1981. During the same period, the exports of electrical machinery increased from 7% to 13%.

It is well known that in the case of South Korea, the government actively assisted strategic sectors to develop, by providing protection and incentives. That is a key lesson for the Sri Lankan Government, instead of leaving it to market forces and blaming the private sector once results are not achieved.

Over-exposure to imports

Secondly, the opening up of the economy since 1977 has resulted in a hurricane of imports. It is clear we depend on imports for the major proportion of our consumption.

Even simple items which could be manufactured locally are imported. The private sector has been just happily importing and selling at a margin to make profits, with very little effort made to increase value addition locally, in the absence of strict guidance from the Government. The annual import bill on vehicles could have reduced if the Government had actively encouraged local production, by attracting one or two large global auto players. Little progress has been made to reduce the exposure to external shocks, such as volatility in crude oil price.

Rupee set to reach new lows eternally

The Government needs to address the above two aspects decisively, by giving clear guidance to the private sector in terms of incentives, protection, and penalties. As for the FTA drive, the key questions that should be answered are: What industries are expected to take off and what would be the export value? What are the export markets? Due to what factors could Sri Lanka capture such markets from the existing exporters? Etc.

If the above are not addressed promptly, the weakness in external current account would continue, and with that the depreciation of the rupee would also continue. At the current level of depreciation, the rupee would be 200 per dollar within the next 5 years, and it would continue to depreciate thereafter as well.

W&Y

The writers could be contacted via [email protected]