Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Thursday, 3 October 2019 01:23 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Uditha Jayasinghe

Sri Lanka’s Southern Province has emerged as an unlikely achiever in human capital development, punching above its weight and performing better than the Western Province despite having a smaller share of economic growth.

The data is included in the latest World Bank Human Capital Development report launched recently. The Southern Province, despite having a much lower GDP than the Western Province, has managed to score higher than the latter which is commonly considered to have the best education outcomes in Sri Lanka as it is also the wealthiest.

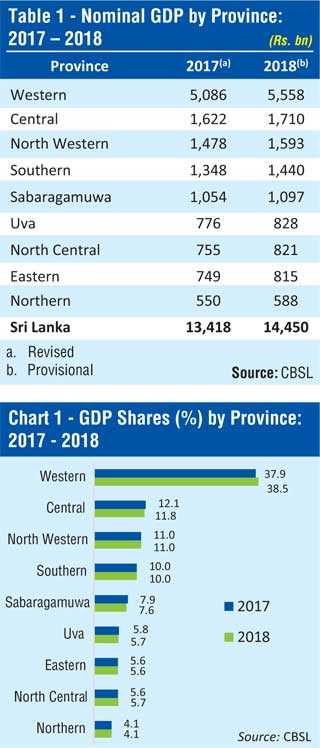

The Western Province according to the latest Central Bank data contributes 38.5% of Sri Lanka’s GDP while the Southern Province only contributes about 10% but the latest World Bank report shows that despite this significant gap the Southern Province has been successful in better education outcomes because it has found solutions to teacher shortages and attracted teachers to underserved Tamil medium schools.

Analysts have pointed out that the data provides encouragement to policy makers at provincial level because it shows that financial wealth is not necessarily the most important when it comes to improving education outcomes and better healthcare but rather targeted policies that are well implemented.

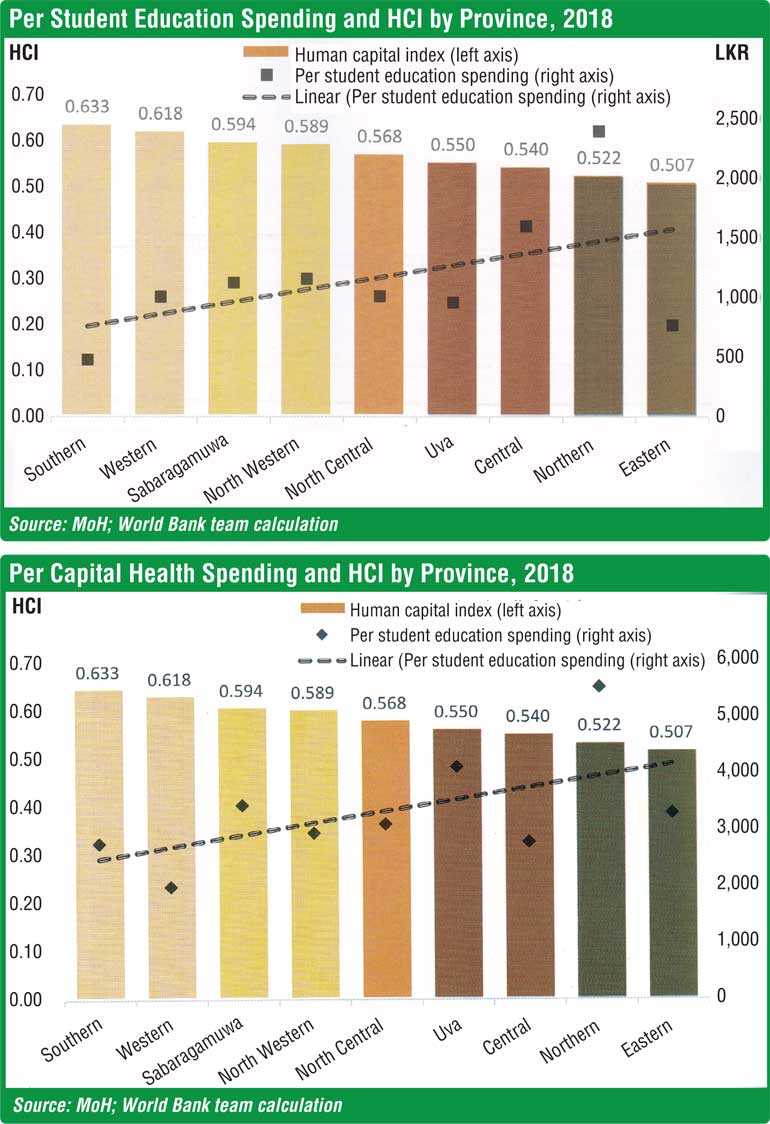

When GDP numbers and human capital index scores are compared it becomes evident that even though the Central Province in 2018 contributed 11.8% of Sri Lanka’s GDP, slowing slightly from 12.1% the previous year, it only lands in seventh place among all nine provinces for per capital health spending and retains the same place for per student education spending. Sabaragamuwa, North Western, North Central and Uva provinces all pose higher scores than the Central Province even though their GDP numbers are much less impressive.

Only the Northern and Eastern Provinces have scored lower but the former has far higher pre-student education spending and per-capita health spending than the latter when compared with the median across all provinces.

“Sri Lanka needs to address human capital development from the twin perspectives of upper-middle-income growth and regional equity,” said Harsha Aturupane, Lead Economist and Program Leader for Human Development for Sri Lanka and the Maldives. “Greater resources and policy attention are needed for provinces where human capital is less advanced, while also making rapid improvements in human capital in the more advanced provinces.”

Overall scores

Sri Lanka performs only moderately well on an overall score of 58%, in the Human Capital Index (HCI) and has a ranking of 74 out of 157 countries. This means that children born in Sri Lanka today will be 58% as productive in adulthood compared to their full potential. In contrast children born in the top performing countries can expect to achieve much higher levels of human capital.

Children born in Singapore can expect to achieve 88% of their potential, Japan and Korea 84% and Hong Kong and China 82%. Even though Sri Lanka is the best performing country in South Asia it lags behind East Asian countries such as China, Malaysia, Mongolia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Sri Lanka performs well in some components of the HCI but performs less well in others. Sri Lanka does well on the probability of children surviving to age five, with 99% of children reaching this age. This is equal to the probability of child survival in high income countries. Sri Lanka also shows strong performance in schooling years with an average of 13 years, which is also on par with high income countries, but the quality of education remains low with a child in Singapore learning the same amount as a Sri Lankan child in just eight years.

Sri Lanka does less well in learning outcomes and stunting rates. On leaning outcomes Sri Lanka has a score of 400, which is slightly above the average but well below the mean score for East Asia and the Pacific. Even though 83% of children in Sri Lanka are not stunted it shows that there is still significant disparity in how provinces fare on healthcare and education.

“The country faces deep rooted challenges in stunting (reflecting chronic under nutrition and learning adjusted years of schooling. These are second generation challenges that are hard to address. Yet they are vital for human capital development and equitable economic growth. Leaning outcomes in particular are a major challenge when compared to the performance and potential demonstrated by advanced education systems in East Asia.”

Good teacher management

The report also found that the Southern Province has the highest HCI value, followed by the Western Province, while the Eastern and Northern provinces had the lowest. The report points out that even though the acceptance is that the Western Province as the wealthiest province does the best on healthcare and education, the Southern Province has managed to have better learning outcomes despite being poorer in terms of GDP.

“The main reasons for the higher learning level in the Southern Province is the close attention of policy makers to good teacher management and development. The Southern Province effectively deployed teachers from schools with teacher surpluses to schools with teacher deficits in a way that minimized disruptions to the family lives of teachers and reduced resistance to teacher transfers. In addition the Southern Province recruited teachers to fill vacancies in remote estate sector schools which had suffered from teacher shortages for many years. This is an encouraging finding for other provinces as human capital development can be promoted faster than economic growth.”

In fact if all of Sri Lanka had been able to meet the leaning outcome numbers of the Southern Province the country would have been ranked at between 51 and 53 in the world rather than 74. The Southern Province is on par with countries such as Turkey, Mongolia and Mauritius, which are richer than the Southern Province. But by that same argument the North and East provinces would have pushed Sri Lanka to be ranked at 93 or 94 on par with countries such as Kenya.

Gender variations in human capital also favour girls and women. Women live longer, spend more time in school and lean better. This is a consistent pattern across all provinces. The gender gap is most significant in the Eastern Province, followed by the Northern, Western and Southern Provinces. These are the provinces with the lowest and highest HCI scores. The gender gap in human capital is significant and suggests that promoting human capitation development among boys is particularly important for policy makers.

Human capital for growth

State Minister of Finance Eran Wickramaratne speaking the launch of the report acknowledged there is a challenge for the Government to shift financial focus away from big infrastructure projects and into efforts such as human capital development. However he warned that this was necessary to continue Sri Lanka’s growth and reduce inequality in the coming years and decades.

“This year Sri Lanka has moved to upper middle income status but we still have 25% of our labour force working in agriculture. This should be reduced to about 10% and the rest should be moved to services. But this is an impossibility in the short run. What kind of economy should we be working on?

“Sri Lanka has lost its concessionary status and has moved into markets, especially money markets to raise loans. Now more than 30% of our debt is made up of market loans that are invested in infrastructure projects that make little returns. We had to come to power and figure out how to pay these back,” he said.

Wickramaratne argued that despite private sector complaints of high interest rates it was essential to promote fiscal consolidation, to reduce the trade deficit and promote more sustainable policies.

“But now we have to move towards growth. We have to have Human Resources development. People are working at the lower level of value addition. Other countries have imported labour but our people don’t like that either. So this is the real problem that we face. We have done the basics well but we have failed to rise about that. The promise of the early years have not been realised.”

The State Minister stressed that Sri Lanka has to have students entering universities and touched on the importance of schools encouraging students to pursue Science, Technology, Engineering, and Maths (STEM) subjects. He pointed out that as much as 63% of schools that offer Advanced Level classes do not have the science stream.

“Sri Lanka’s human resource is not up to the mark when compared with East Asia. There is no better investment that a country can make than in early childhood education. Universal free pre-school education. I would like to see Sri Lanka and the World Bank work together to achieve that goal.”

World Bank Country Director for Nepal, Sri Lanka and the Maldives Dr. Idah Pswarayi-Riddihough addressing the gathering said developing human capital to a new and higher level will be key for Sri Lanka to become the upper-middle-income economy it seeks to be.

“People are the most valuable resource in any country and investing in people is smart economics,” said Dr. Pswarayi-Riddihough. “Technology and automation are radically changing the very nature of work and reshaping industry. Children in primary school today are likely to work in jobs that may not even exist right now. Since education and health are both subjects that are devolved to the provinces, provincial level policy makers and officials will find these results particularly useful, enabling them to chart their way forward and formulate policies accordingly.”

Math and English learning outcomes

The report found there are considerable gender differences in mathematics learning outcomes. At the national level girls have an average score of 418 and boys have an average score of 383. In all provinces girls outperform boys.

The gender gap is largest in the Eastern Province where girls score 353 and boys score 295, resulting in a difference of 58 marks. The second largest gender gap is in the Western Province with girls scoring 446 and boys scoring 405 leading to a difference of 41 marks. The gender gap is lowest in the Central Province with six marks and the North Central Province, which has 10 marks. However, in all the other provinces the gender gap is at least 27 marks, which is a substantial difference.

Gender differences in English language learning outcomes are also large. At the national level girls have an average score of 432 and boys have an average of 365. In eight of the nine provinces girls outperform boys with the Eastern Province, where boys score slightly higher than girls as the sole exception. The largest gender gap is in the Western Province with girls scoring 510 and boys 404, leading to a difference of 106 marks.

There are also large gender gaps in favour of the girls in the Uva Province, 87 marks, Sabaragamuwa Province 83 marks and Southern Province 29 marks. The gap is lowest in the Central Province 30 marks and the Northern Province 37 marks. However, even in these provinces the gender gaps are considerable.

The report provides vital insights for policy makers looking to make the most out of limited resources and generate the most equitable and quality outcomes for Sri Lanka’s development.

Pix by Chamila Karunaratne