Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 27 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Nisha Arunatilake

and Ashani Abayasekara

Deepani is a Grade 10 student who loves mathematics and science. Her parents are delighted and encourage her to continue in these fields, assuring her that she will have a bright future. But Deepani is worried that she is not learning all that she should – her teachers in both subjects are not the best, and at times Deepani has been unable to clarify doubts in certain areas. Deepani wonders whether she can continue in the field of sciences, if her teachers lack the competency to instruct and guide her. Without doing well in mathematics and sciences at the Ordinary Level Examination (O-Levels) next year, her dream to continue her studies in the science stream will be futile.

Deepani is a not alone in her concerns. IPS research finds that at present, close to half the students who sit for O-Levels fail the exam. In fact, being unable to meet the minimum requirement of a credit pass (C grade) in mathematics or science at the O-Levels is the main reason for the low number of students in science streams in the Advanced Level (A-Level) classes. According to the 2016 School Census Preliminary Report, even of those who continue on to sit for A-Levels, less than a quarter (23%) is in the science stream, while only a further 10% is in the technology stream. The majority (66%) are in the arts and commerce streams. Similarly, the distribution of students in public universities is highly skewed towards the arts and social sciences, while enrolments in the natural sciences are much lower.

Generating a high share of university graduates, especially in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) subjects, is a policy priority for Sri Lanka, given the country’s goal of becoming a knowledge-based economy, driving competition through innovation. The 2018 Budget Speech correctly identified the need for “improving the ratio of STEM to non-STEM graduates in the country”. The foundation for STEM education at the graduate level needs to be laid at the school level. Only those with a good foundation in general education will move on to tertiary level education, especially in STEM subjects.

A recent IPS research study highlights the need for good quality teachers for improving education outcomes of children at the O-Levels. A complimentary recent study examines the adequacy of quality teachers to teach science, mathematics, and English at the secondary level in the country. This article summarises the main findings of the study.

Surplus of teachers, but not enough subject-qualified teachers

According to the 2016 school census data, Sri Lanka has an overall surplus of teachers who usually teach mathematics and science subjects; that is, the number of teachers who mostly teach mathematics and science are more than the number recommended by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in the first circular of 2016 on determining staff numbers in a school.

However, this does not mean that all these teachers are subject-qualified. A teacher with either a degree or a specialised training in a particular subject is considered as a subject-qualified teacher. Even though in many countries teachers need to be especially certified to teach a subject, Sri Lanka’s teacher service does not have such a requirement.

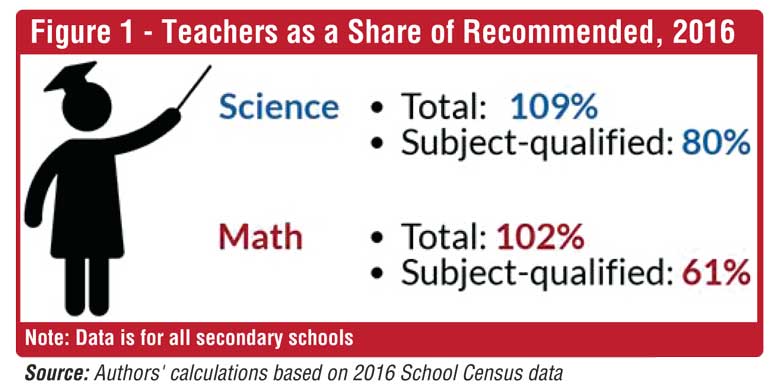

As Figure 1 indicates, the shares of available teachers are more than the recommended number of teachers (over 100%), indicative of overall teacher surpluses. Nevertheless, the shares of subject-qualified teachers are much lower than the recommended number of teachers.

Issues with the Allocation of Teachers

The MOE clearly provides guidelines on the number of teachers recommended for each school, based on the number of classes, availability of subjects, and the languages of instruction offered by the schools.

However, our analysis shows that some schools have an excess of science and mathematics teachers, while others are sorely lacking in this regard. Our findings also show that more affluent schools, attended by wealthier students, have better teachers than less-advantaged schools.

Unsystematic recruitment of teachers

Unsystematic teacher recruitment is one reason for the inadequacy of teachers. If teacher recruitments are properly planned, the number of teachers recruited should roughly match the number of teachers leaving the teacher service. But, an analysis of school census data shows that teacher recruitments are done haphazardly and arbitrarily. In some years more than 20,000 teachers are recruited, while during other years less than 5,000 teachers are recruited.

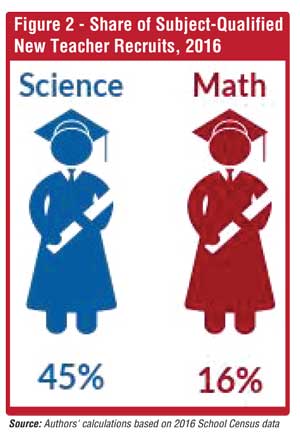

Also, teachers are often not matched to their subject-related education and training at recruitment. As Figure 2 shows, of the total number of science and mathematics teachers joining teacher service in 2016, only a fraction was subject-qualified.

Limited pre-service teacher training opportunities

The numbers of teachers trained by pre-service teacher training programs are not adequate to meet the demand arising for teachers each year. The majority of teachers recruited to the teacher service in Sri Lanka are untrained graduates, followed by those with a National Diploma in Teaching (NDT). Untrained graduates have a degree, but do not have pedagogical training. Those with NDT are trained teachers without degrees. This is in contrast to the best practices in other countries.

In most countries, a degree and a certificate in specialised teacher training is necessary to become a teacher. In Sri Lanka, only those who join the teacher service with a Bachelor of Education (BEd) have both a degree and specialised teacher training. But, school census 2016 data show that only a very small share of those joining the teacher service hold a BEd.

Policy recommendations

There is an urgent need to improve pre-service teacher training, currently offered at the National Colleges of Education and at universities, to match the demand for STEM teachers in schools.

Improving and expanding the pre-service training of teachers and giving priority to recruiting teachers with proper pre-service training can help improve the availability of qualified teachers. Such training programs should especially cater to the demand for teachers in different subject areas. Teacher training should also be well planned to meet the requirements of the teacher service.

Further, teachers should be certified to teach different subjects and the subject knowledge of teachers should be taken into consideration when filling vacancies.

Lastly, teachers should be allocated to schools according to need, so that no school has an excess of teachers, and teachers are evenly distributed across all schools. Allocating teacher cadres for schools according to the available classes, subjects, and mediums of instructions, can prevent schools from recruiting teachers in excess.

Unless qualified teachers are available in all classrooms, many students like Deepani will not be able to realise their dream of pursuing higher studies in the science and technology field. Unless students interested in science and mathematics are encouraged from a young age, and are given proper guidance, expanding science education at the tertiary level will remain a pipedream.

(Nisha Arunatilake is Director of Research and Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS).To share your comments with the authors, please write to [email protected]/[email protected]. For more articles, visit our blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)