Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 1 October 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Community support can include providing services such as counselling, support and communication on IYCF, screening for acute malnutrition and following-up of malnourished children, deworming, and delivering micronutrient supplements – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Priyanka Jayawardena

Background

Background

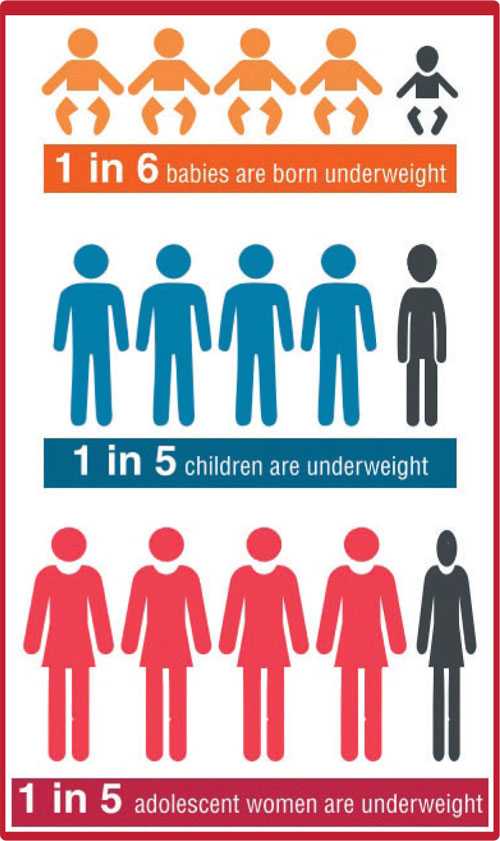

Child malnutrition is still a prevalent challenge in Sri Lanka. More than one in five children (under five years old) are underweight and one in six babies are born underweight. To date, successive governments have taken many measures to improve child and maternal nutrition. However, the situation has improved only marginally during 2006-2016. Improving nutritional status is essential to reduce extreme poverty and achieve sustainable development in the country. It also contributes to productivity growth and economic development and reduces state expenditure on healthcare.

Causes of child malnutrition

Recent IPS research on child malnutrition reveals that the ‘life cycle effect’ is one of the main contributors to the higher prevalence of child malnutrition, especially among the poor. For instance, a mother’s poor nutritional status during pregnancy leads to underweight births; being born underweight leads to growth retardation in childhood, which then causes nutrition issues in adulthood, thus continuing the malnutrition cycle.

Further, findings of the study reveal that dietary issues are caused by food insecurity and the lack of awareness about proper nutrition among poor people. Not consuming enough animal protein significantly increases the prevalence of child malnutrition, especially among the poor. The reasons for this are food insecurity, knowledge gaps, and socio-cultural practices. Further, growth failures significantly increase with the child’s age, pointing to dietary issues during the weaning period. Moreover, the study reveals that a mother’s lack of education also contributes to the higher prevalence of child malnutrition among lower-socio economic groups.

Do Government responses address these issues adequately?

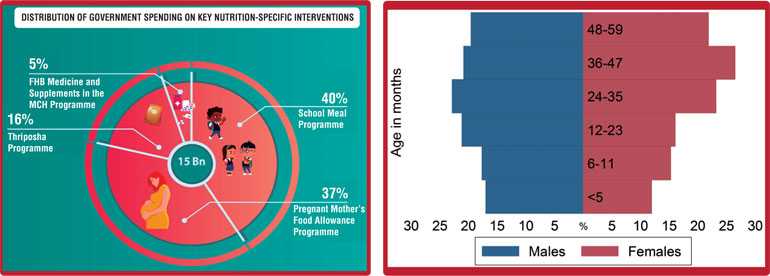

National nutrition policies recognise that to solve the malnutrition issue, it is crucial to address the ‘life cycle effect’. Sri Lanka currently practices most of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) recommendations, including life course interventions under the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) programs, carried out by the Family Health Bureau (FHB). The Government should consider allocating more resources for those MCH programs to improve the quality of supplements. Currently, FHB medicine and supplements in the MCH program accounted for only 5% of the total nutrition-specific spending. Further, some gaps can be noted regarding interventions for pre-pregnant women (22% of 15-24 aged women were underweight) in terms of quality and coverage.

To address existing dietary issues, effective communication on nutrition counselling – Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices – and a healthy diet are critical. However, presently around 0.2% of the total nutrition-specific investments has been utilised on nutritional awareness and promoting communication programs aimed at changing behaviours. Awareness programs and educational and promotive activities deserve more funds and resources to proactively combat malnutrition.

Timely access to quality health services is a key factor in the successful management and treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF) BP-100, is used to treat SAM children. Although, BP-100 is in the form of a compressed biscuit/bar, to be used in the community settings, in Sri Lanka, it has to be prescribed by a paediatrician at the district hospital level or higher. Service coverage is limited for SAM treatment due to the low demand, the lack of active case identification, and the limited access to services in some provinces. Also, there is no data available on the performance of existing services to treat SAM (e.g. coverage, treatment outcomes, etc.), making it difficult to assess its outreach and success.

Study findings point out the need to rebalance public financing towards better targeted, evidence-based interventions. The country’s annual public investment on key nutrition-specific interventions is approximately around Rs. 15 billion. Of these investments, 40% was absorbed by the school meal program, followed by the pregnant mother’s food allowance program (37%) and Thriposha program (16%). The FHB medicine and supplements in the MCH program accounted for only 5%. However, there concerns about the effectiveness of nutrition interventions such as Thriposha program and pregnant mother’s food allowance program, on which the Government spends nearly half of the total nutrition-specific interventions.

Further, a blanket provision for some nutrition programs appears to be costly. For instance, the expansion of the pregnant mother’s targeted food allowance program to a universal program in 2015 was a substantial expense. Thus, the Government’s annual expenditure on food allowance for pregnant mothers has increased by more than Rs. 5 billion.

How to improve the effectiveness of policy responses

The Government should consider improving the quality of the MCH supplementation program by the FHB, as it covers the entire life course interventions, as recommended by the WHO. Formulating nutrition specific interventions requires due attention, especially those related to the first 1,000 days (the most crucial time to meet a child’s nutritional requirements – i.e. mother’s pregnancy period and the first two years of a child’s life). Further, to improve the coverage of pre-conception women, separate services for adolescents may be more appropriate as they may not like to use general MCH services and prefer facilities that are specially designed for young people.

The following strategies are recommended for better targeting pre-conception women – implementation of nutrition intervention programs and regular screening tests at workplaces as well as community-based organisations that provide services to adolescents and youth.

Potential room for efficiency gains by optimising resource allocation for more targeted interventions. In light of the amidst issues like effectiveness and coverage gaps about some existing nutrition interventions, staple food fortification is much appropriate for Sri Lanka as a preventive food-based intervention to improve micronutrient status of populations, as recommended by the WHO. There is potential to gain some fiscal space by changing the supplementary feeding program (Thriposha), for pregnant and lactating women, to target pregnant women at risk rather than all. Likewise, pregnant mother’s food allowance program should be targeted in deprived regions.

Effective communication on nutrition counselling – IYCF practices and healthy diet; screening for acute malnutrition and follow-up of malnourished children are critical elements of nutrition interventions. Nutrition education programs should be strengthened to inculcate better consumption habits – what foods to select, how to prepare and feed children, and the hygienic and nutritional value of food. It is vital to raise awareness on healthy behaviours. Further, school level and community-based management are globally recommended interventions, in treating SAM children. Community support can include providing services such as counselling, support and communication on IYCF, screening for acute malnutrition and following-up of malnourished children, deworming, and delivering micronutrient supplements. Another intervention is building strong monitoring and evaluation frameworks to measure program performance. A rigorous prioritisation exercise is recommended to investigate the effectiveness, the cost-effectiveness, and the good practices of nutrition interventions.

(This Policy Insight is based on findings of the study ‘A Proactive Path to Combat Malnutrition in Sri Lanka’ by IPS researcher Priyanka Jayawardena. Please email [email protected] for more information.)