Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 3 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Bilesha Weeraratne

Remittances make an indispensable contribution to the Sri Lankan economy. In 2018, despite experiencing a decline for the second consecutive year, the country received remittances of over $ 7 billion, accounting for 7.9% of the GDP.

Often, remittances to Sri Lanka are attributed to the temporary migrant workers and viewed from a national perspective. Nevertheless, as highlighted in a recent IPS study by the author, there are more dimensions to remittances. This blog examines the nuances of receipt of remittances, at the household level in Sri Lanka.

Migrants vs. remitters

Micro level analysis by the author, using the latest available nationally representative household data, shows that on average, a remittance-receiving household in Sri Lanka collects Rs. 259,456 per annum. At the same time, 7.07% of households in Sri Lanka have a migrant abroad, and larger share of households receive remittances. To be specific, there are 8.76% remittance-receiving households and the gap between migrant and remittance receiving households is 1.69 percentage points.

This difference in the share of migrant households and remittance-receiving households indicate that either migrants are remitting to more than one household in Sri Lanka, or in addition to those considered migrants originating from Sri Lanka, there are others remitting, or a combination of both these scenarios taking place. But who could be the other remitters to Sri Lanka?

One answer is permanent migrants or diaspora. Permanent migrants often leave with their immediate family, leaving no one behind to report them as migrants in household level surveys. Nevertheless, such permanent migrants, and subsequent second and third generation migrants and diaspora may still be connected with extended family and friends, and continue to send remittances. Similarly, there could also be other individuals or organisations without a person of Sri Lankan origin, but remitting to Sri Lanka for various purposes.

Geographic variation

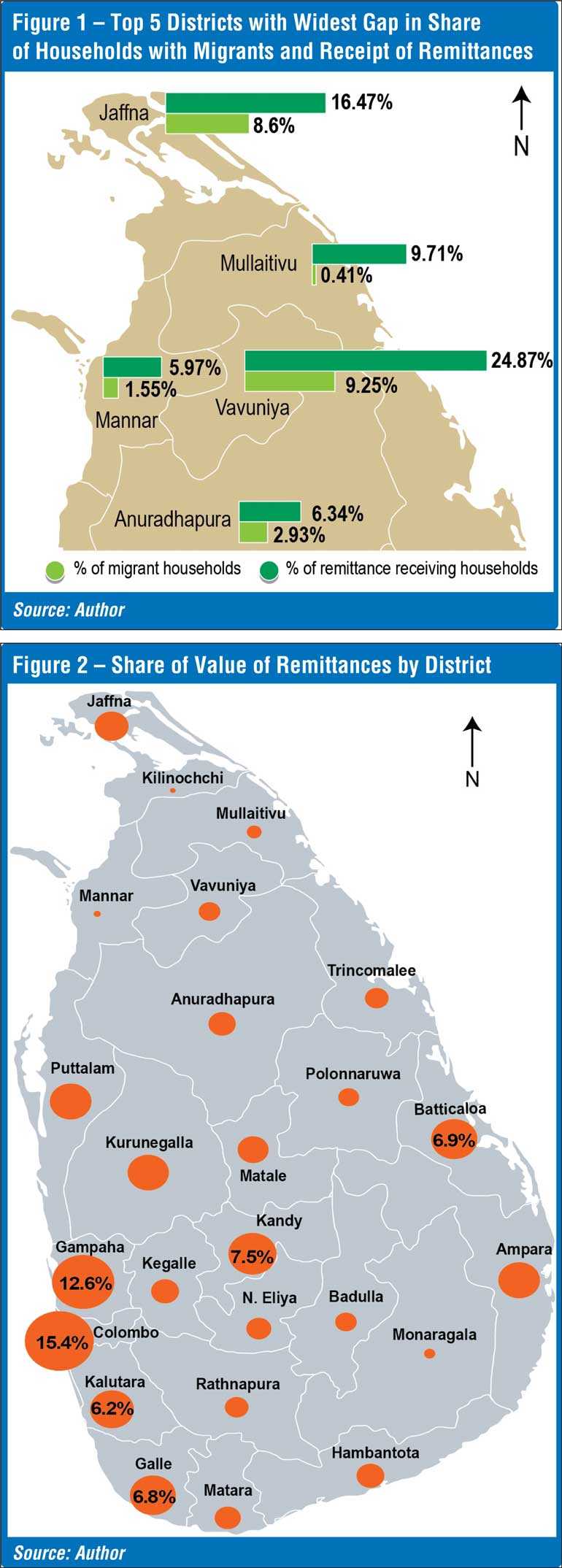

The presence of more remittance-receiving households than migrant households has a large geographic variation at the district level.

As indicated in Figure 1, Mullaitivu has the widest gap between migrant and remittance-receiving households, where compared to the less than 0.5% households in the district having a migrant abroad, the proportion of remittance-receiving households (9.71%) is nearly 24 times the former. In Mannar, where 1.55% households have a migrant abroad, four folds or nearly 6% households receive remittances. Similarly, in Vavuniya, where 10% households have a migrant, nearly a quarter of households receive remittances.

As such, Vavuniya records the highest proportion of remittance receivers, where nearly one in every four households get remittances. The other top four districts with the highest share of remittance-receiving households are Batticaloa (21%), Jaffna (16%), Ampara (12%), and Mullaitivu (10%). These findings indicate that, in the Eastern and Northern Provinces in Sri Lanka, remitters are less likely to be migrant workers and more likely to be diaspora and others sending remittances to Sri Lanka.

Share of remittances

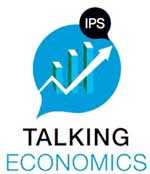

As evident in the above discussed geographic variation, the Eastern and Northern Provinces are emerging as prominent sources for remittances in Sri Lanka. Nevertheless, in terms of the value of remittances received, the Western Province takes the lead.

For instance, Kalutara District records the highest average household remittances of Rs. 383,557, followed by Colombo, with Rs. 369,792. Interestingly, despite a nominal share of households with migrant and receipt of remittances, Hambantota District records the third highest average household remittances with Rs. 353,865.

In terms of share of total value of remittances received by district, Colombo ranks first, accounting for 15.4% of total value of remittances received by households in Sri Lanka, followed by Gampaha with 12.6% and Kandy with 7.5% as second and third, respectively. Similarly, Batticaloa accounted for 6.9% and Galle for 6.8%, in fourth and fifth places, respectively (Figure 2).

Make the best of regional variations

The study finds that there are significant geographic variations in receipt of remittances at the household level. This understanding about the nuances of these geographic variations can be utilised for effective and targeted policy formulation. The noticeable gap in remittance-receiving households in excess of migrant households in the Eastern and Northern Provinces indicates that remittances come from sources beyond migrant workers.

On the one hand, in the backdrop of concerns for foreign funding for terrorism associated with the Easter Sunday attacks, greater attention is required ensure that remittances to Sri Lanka are not a façade for financing terrorism or money laundering. Specifically, given that the inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force has identified Sri Lanka as a ‘high risk third country’, with strategic deficiencies in anti-money laundering and countering financing of terrorism laws, careful scrutiny is needed to understand the true facts behind remittances, and refine or introduce required laws accordingly. On the other hand, the latest data indicate that the poverty head count is highest in the Northern and Eastern Provinces in Sri Lanka. Given that it is widely accepted that remittances have an inherent capacity to be well targeted to reduce poverty, and is associated with minimum corruption in disbursement, this greater significance of remittances over migration in these provinces should be harnessed to address poverty and improve their regional economies.

As such, nuanced details of remittances in Sri Lanka ought to be effectively integrated into policy formulation, to leverage remittances to improve anti-money laundering and countering financing for terrorism efforts, as well as to improve regional economic opportunities in Sri Lanka.

(Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)