Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 26 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sanja De Silva Jayatilleka

The 72nd UN General Assembly, which President Maithripala is currently attending, has already gained notoriety around the world, because unusually, one of its member states threatened to totally destroy another.

Ahead of it, on 18 September, President Sirisena joined other world leaders in adopting a Political Declaration for UN Reform “to initiate meaningful reform to make the UN a more effective and efficient organisation”. The new UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres pledged to overhaul the United Nations bureaucracy to make it more responsive to the people it serves.

While this is a welcome initiative by the new Secretary General, it is hoped that Reform of the UN does not remain limited to rationalising its bureaucracy. The UN, as the premier multilateral organisation in the world needs to be more democratised if it is to be representative of its members and therefore more effective.

That need became even more evident following the threat to annihilate North Korea. Several countries have been engaged in efforts to defuse tension in the Korean peninsula through diplomacy, which is the only safe track when one is dealing with a nuclear power. One wonders what went through the minds of the South Korean delegation!

The new Secretary General has his work cut out, aiding the member states to recall the role of the United Nations and its guiding spirit. It is hoped that strengthening the General Assembly is one of the reforms he has in mind to propose to the UN member states.

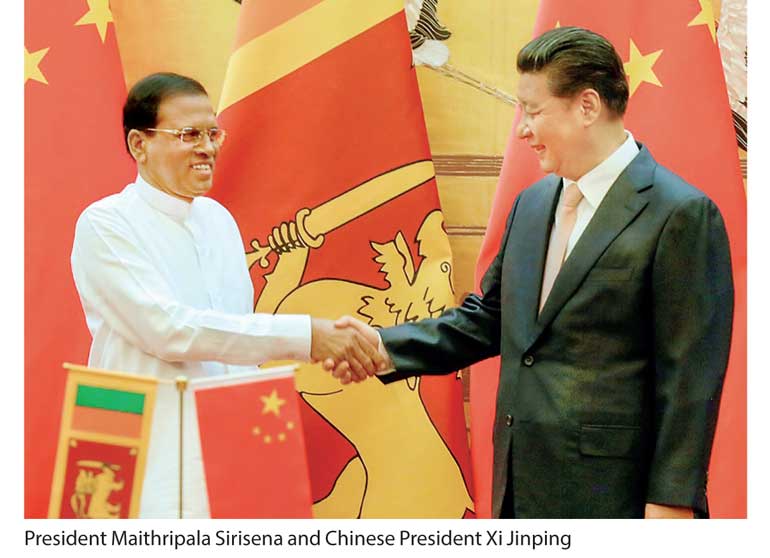

As China celebrates its 68th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic, it is useful to recall its views on UN reforms. Despite its privileged position as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, it has often expressed its desire to make UN decision making more inclusive. China has learnt from its long history that “a wise man changes his ways as circumstances change” as the Chinese saying goes, and that “the ocean is vast because it is fed by many rivers”, to quote Chinese President Xi Jinping.

China has called for regional representation at the UN Security Council (UNSC) and closer links between the UNSC and the UN General Assembly (UNGA) “to have more small and medium sized countries… to have more input into the decision making of the UNSC”. The Human Rights Council, a late addition to the UN system has adopted the model of regional representation for its membership. This is achieved by a rotational Presidency and four regional Vice Presidencies and regular elections for membership of the Council based on equitable geographical representation, making the UN Human Rights Council representative of the peoples of the world.

On 4 September, at the ninth BRICS Summit held at Xiamen International Conference Centre, President Xi Jinping said: “We need to make the international order more just and equitable. Our ever closer ties with the rest of the world require that we play a more active part in global governance. Without our participation, many pressing global challenges cannot be effectively resolved.” China sees engagement with global governance as the duty of an emerging power.

For a few years, under President George W. Bush, the United States refused to participate at the UNHRC. When it decided to contest for a place, it was promptly elected. However, US Ambassador Nicky Haley declared at her press conference in New York last Friday that they had made their views very clear at the meeting on Human Rights Reform that they were not happy at “the quality of countries” elected to the UNHRC, and if things didn’t change, they would pull out. The US participation is clearly conditional.

The thing is, member states are elected to the Human Rights Council by a vote of the General Assembly in New York where all 193 member states are represented. There is no way around democracy of that sort. One cannot demand to have only the states one approves of in the Council. Staying in and negotiating a better world is considered more useful than storming off.

This is not the only time that the US threatened to pull out during the first week at the UNGA this month. It also threatened to pull out of the Iran Nuclear deal. That deal was painstakingly negotiated in 2015 by several countries (all five permanent members of the UNSC: US, China, Russia, Britan and France, plus Germany and a representative of the EU, and Iran), and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna has confirmed repeatedly that Iran was not in violation of any of its provisions. US Secretary of State admitted at the UN that Iran “is in technical compliance with the agreement”, and cited its “destabilising activities” in the Middle East as a reason for the threat to exit the nuclear agreement. None of the other signatories support this position.

Unilateral action of this sort is hardly an example to follow. And yet, according to the Sunday Times (Colombo), the new edition of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) open for signature last week, the first multi-lateral disarmament treaty in more than two decades, has not been signed by Sri Lanka. It asks editorially “The questions seem to be which super (nuclear) power or powers twisted our arm not to sign the treaty, or who were we trying to please.” It hopes that this is “not a precursor to Sri Lanka’s departure from an independent foreign policy and signalling a dance to the tune of any one, or more foreign powers.”

China’s view on the UN and multilateral diplomacy is consonant with the national interest of Sri Lanka. President Xi addressing the BRICS summit emphasised the importance of multilateralism: “We should remain committed to multilateralism and the basic norms governing international relations, work for a new type of international relations…”

An earlier position paper from China on UN reform dealt with the ‘Responsibility to Protect’ declaring that “When a massive humanitarian crisis occurs, it is the legitimate concern of the international community to ease and diffuse the crisis. Any response to such a crisis should strictly conform to the UN charter and the opinions of the country and the regional organisation concerned should be respected.”

Given the coalitions we belong to, this view is congruent with Sri Lanka’s own view of its interests. Led by President Sirisena, the Sri Lankan delegation in New York is scheduled participate in the Non-Aligned Movement Ministerial Meeting, the Informal Meeting of the SAARC Council of Ministers, the Ministerial Meeting of the Commonwealth, the Ministerial Meeting of the Asia Cooperation Dialogue and the Group of 77 meeting.

At the BRICS summit, President Xi quoted an ancient Chinese saying which goes: “A partnership forged with the right approach defies geographical distance; it is thicker than glue and stronger than metal and stone.” This is very different to the saying, perhaps closer to reality and often quoted, that goes “In international relations, there are no friendships, there are only interests.”

The first is an Asian aspiration, while the second is the hardnosed realism of the West. Sri Lankan leaders have often used phrases that indicate an affinity with the first perspective when they say that “India is like a relative, with cultural ties that go back thousands of years”, or “we have had relationships with China since ancient times when we were an important post on the Silk Route”. The inference is that those old, organic, civilisational ties should count for something.

Sri Lanka did have strong ties with both these countries without necessarily playing them off against each other. Indeed it was known to have good relationships with countries around the globe. A long war such as the one that we fought was bound to be globally polarising to some degree. Even so, in its wartime first term the previous Sri Lankan Government succeeded in handling international relations wisely, successfully negotiating political and military support in its fight against terrorist separatism through effective and sustained diplomatic engagement with the world. However, other mistakes saw even its closest neighbour applaud its exit. The successful handling of global diplomacy took a tumble in its second term and soon after, the Government itself took a tumble.

The new (and current) Government made its own mistake, starting well before it was elected. We will never as a country be able to recover from that mistake until we admit it squarely. In its zeal to win the election, it sacrificed Sri Lanka’s vital national interests by repeatedly denigrating the large-scale Chinese projects of enormous value, and promised to stop them if they were elected.

The new team of politicians showed a distinct lack of maturity and pragmatism in trying to woo the West and India, unable to do so without damaging the relationship with the world’s biggest investor currently and for the foreseeable future. Having stopped the Chinese projects, it overreached and had to eat humble pie. The 99-year lease of the Hambantota Port was a direct consequence. Could Sri Lanka have managed its relationship with China better? Was the Government left with no choice but to make those unpopular choices of sell offs and long leases?

In seeking a different trajectory for Sri Lanka, the new Government has been unable to reconcile its need to align itself with the West with getting the best deal from a cash-rich China which has no reason to trust this Government beyond a point. It has been left trying unsuccessfully to explain the deep trough it has got itself and the country into as a result.

Addressing the Boao Forum for Asia Annual conference in 2013, President Xi said in his keynote speech that “China cannot develop itself in isolation from the rest of Asia and the world. On their part, the rest of Asia and the world cannot enjoy prosperity and stability without China.” It is hoped that Sri Lanka joins the rest of Asia in weaving this reality into their foreign policy calculations.