Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 4 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Meera Srinivasan

The Hindu: When Sri Lankan author Anuk Arudpragasam recently received the DSC Prize for South Asian literature, the honour shone the international spotlight on the country’s gruesome civil war, yet again. Except that this time, it was a novel that drew attention to it.

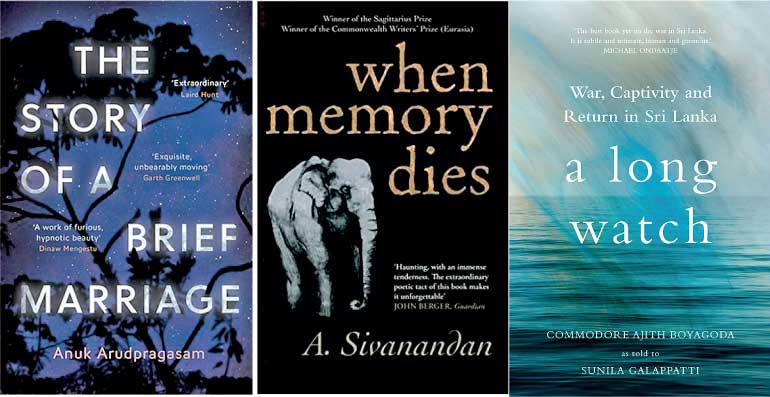

‘A Story of a Brief Marriage’ is Arudpragasam’s debut novel published in 2016. A Ph.D candidate at Columbia University, the young author has received accolades for his poetic language and attempt to capture the nuances of a war through everyday ordinariness.

“There are many ways of depicting it [the violence] but I chose to depict a person going through very ordinary human processes — walking, sleeping, eating, shitting. Because in such a situation a person wants to retain their humanity,” he told Vaishna Roy of The Hindu in Dhaka.

In most media interviews that followed the recognition, Arudpragasam spoke about his privileged class location in Colombo, and about the modest reach that an English novel like his will have in the South Asian context.

Many English language writers from Sri Lanka and others abroad have, over the last three decades, written non-fiction accounts of the island’s Sinhalese-Tamil ethnic conflict and the war it entailed. London-based Sri Lankan author A. Sivanandan’s 1997 classic ‘When Memory Dies’ spoke of a country broken by colonial occupation and torn apart by ethnic divides.

However, not too many English novels followed in the years of a heightening war. ‘A Story of a Brief Marriage’ stands out as a rare work of fiction coming out of post-war Sri Lanka. It is, perhaps, the only English novel till date that has zoomed into the routine brutality encountered by an individual in the last phase of the war that ended in 2009.

Despite the widely-held view that conflict or turbulence tends to be a wellspring of powerful art and literature, there aren’t too many English novels on the Sri Lankan war. English literature has been relatively slower to respond to the conflict that engulfed the country, say authors and literary critics. They point to many reasons ranging from distance by location or class, to style, purpose and target audience. Some argue that it is a question of time. Good literature, in their view, might need more time for a deeper perspective on a protracted war.

To some extent, Sinhala writing has also faced a similar challenge — one of distance, while making sense of a war set in the island’s Tamil-majority north. Tamil fiction, on the other hand, has rapidly responded to the war, with an apparent immediacy and urgency. Hundreds of novels and short stories speak to the conflict in general, and the war, in particular.

Change in narrative

Sunila Galappatti, author of ‘A Long Watch’ and former Director of the renowned Galle Literary Festival, says: “I sometimes think we are only just starting to outgrow the sort of self-orientalising storytelling that was encouraged for some years in South Asian fiction in English; those books that were written for readers far away, or hopefully addressing the air.”

In her view, it is only when authors start writing for each other, “for people who know as well as we do the things we are describing”, that they can find new rigour and urgency in the way they write. “My feeling is only then will we also be ready to try describing Sri Lankan fiction in English,” she says.

A prodigious output

As far as Tamil and Sinhala fiction are concerned, they seem to tell a slightly different story.

Tamil fiction, on the other hand, has rapidly responded to the war, with an apparent immediacy and urgency. Hundreds of novels and short stories speak to the conflict in general, and the war, in particular.

According to Sivamohan Sumathy, Professor in English, University of Peradeniya, the rise of radical militancy and the accompanying literary output created some very powerful Tamil literature. “But this is not a one-dimensional nationalist output. It is said that M.A. Nuhman’s translations of Palestinian poetry were an inspiration for those activists among the Tamil youth that sought a language of liberation,” she says.

Effortlessly listing titles of Tamil novels published over the last seven decades — right from the 1960s — Kilinochchi-based Tamil author and journalist Karunagaran points to Mu Thalayasingham’s ‘Oru Thani Veedu’ (A Separate House), Arul Pragasam’s ‘Lanka Rani,’ People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE) member Govinthan’s Puthiyathor ‘Ulagam’ (A New World) and Shobasakti’s ‘Gorilla’ and ‘Hmm’ as some of the important novels pegged to the conflict.

“There are many, many other very important short story collections and novels, especially those written by women-authors like Thamilini and Malaimagal, who wrote on the experiences of women combatants,” he says.

Broadly, Karunagaran classifies Tamil fiction along two tracks – works that are sympathetic to the armed struggle, and others of “dissenting literature”, where writers — many of who were part of different militant groups — questioned militant movements on their apparent lack of democracy within.

“In my view, dissenting literature has become more popular now, especially among younger readers. In fact, younger writers are also beginning to use a more critical lens to look at their past. This sort of honest, reflective writing from within the Tamil community is a very positive trend,” he says.

Prof. Nuhman, senior Tamil academic, poet and literary critic, observes that while many Tamil novels endorsed a nationalist politics, authors such as Shobasakti made a crucial literary intervention, bringing in other narratives to the story of the civil war. “Authors who have had first-hand experience of the war write with a certain intensity that only a lived experience can bring to one’s writing,” he says.

While there was initially a ready rejection of any criticism of Tamil militancy – some Tamil militant groups did not permit the publishing or release of some of the critical novels in Sri Lanka, forcing writers to seek out publishers abroad — the space for that literature has opened up, authors note.

Minority report

Authors such as Oddamavadi Arafath wrote on the experiences of the Muslim community during the war. Some Muslim writers have written subtle commentaries on the sufferings of the Muslims at the hands of the Tigers. Some like Sharmila Seyyid have had to deal with enormous flak for her sharp critique of Tamil nationalism and of the “Talibanisation” of the Muslim community in eastern Sri Lanka. Mounting threats from within her community pushed her into self-exile a few years ago.

Meanwhile, progressive Sinhala fiction has often dealt with the leftist JVP-led youth insurrections in the early 1970s and late 1980s. While many writers were sympathetic to the insurgent youth taking on a repressive, capitalist state, they were quick to challenge the JVP’s nationalist politics and its position on the Tamil question through their writings, says Liyanage Amarakeerthi, author and professor in the Department of Sinhala at the University of Peradeniya. His own novel ‘Atawaka Putthu’ (Half Moon Sons) is considered an important work on the theme.

“There are some excellent short stories with the civil war as the background, but I suppose for most novelists the war was something ‘far away’. There is a distance,” says Prof. Amarakeerthi.

In the island’s Sinhala-majority south, he notes, there is a tendency to celebrate soldiers as “war heroes” after the war, preventing any critical self-reflection. “Moreover, I think the sense of victory in some cases, or the sense of guilt in others, comes in the way of writing. The Sinhalese who encountered the war closely were mostly soldiers and if they write novels at a later point, we may get some wonderfully intimate takes on it. I think it is too soon to have significant literary output on the war in Sinhala.”

Growing interest

All the same, there is a big appetite among readers for political novels in Sinhala, observes H.D. Premasiri, Managing Director of the Colombo-based publishing house Sarasavi Books. “Such novels sell up to 30,000 copies in original. Short story writers are now increasingly dwelling on the civil war,” he said, adding that translations of good novels from Tamil to Sinhala also do well.

Prof. Amarakeerthi, who teaches a course on Tamil literature in Sinhala translation, observes that given the language divide in the country, translations are a crucial bridge to accessing important writing in Tamil.

Short stories in Tamil have provided a sharp incisive commentary on society, showing a multidimensionality of feeling, social structure, and a sensitivity to difference, Prof. Sivamohan notes. “I have found the English short story rather tame in comparison. In recent years, both English novels and short stories have taken on interesting forms. ‘Chinaman’ by Shehan Karunatilaka and ‘The Jam Fruit Tree’ by Carl Muller, to name just two. English writing in general is stuck in the middle-class milieu of its location, and hardly problematises any of its assumptions. This is where the ultimate weakness in English fiction lies.”

Some authors also see time as a crucial factor that shapes writing. Galapatti notes: “The first books written are rarely the best (and I say that as someone who has written one herself!). If nothing else, we are very close to our history, and we may not be the people who will see deep into it.”

The books written today, she hopes, will be used by future authors for research purposes, “to recognise how little we understood about ourselves.”