Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 13 February 2020 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Natalie Blyth

Should a company’s responsibility begin and end with shareholders, or extend to customers, communities, and the environment?

This year will witness renewed debate around the purpose of business evolve into demands for tangible action. Far from shying away, business leaders are embracing the challenge. For instance, look at the recently concluded World Economic Forum. Almost all of its 329 featured speakers, pondered over some facet of sustainability. Not surprising when the event was conducted under the banner ‘Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World’.

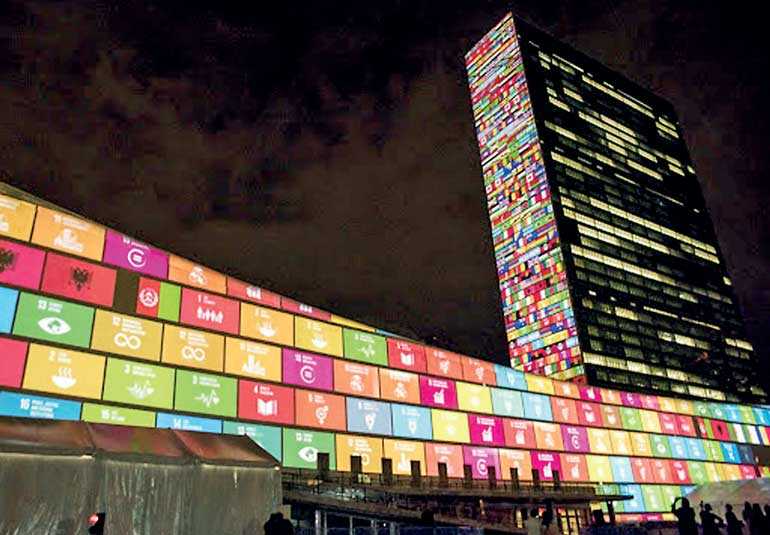

HSBC’s Navigator research reveals a business community ready to address societal challenges; 75% of UK businesses recognise their role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the United Nations (UN) designated blue-print of a sustainable future for all. This is higher than any other European country, and significantly above the global average of 63%.

These findings are significant and, for me, not unexpected. Significant, because with little over a decade to deliver the UN targets, progress is nowhere near on track and the window for action is now. Any hope of achieving these goals will require businesses to enact the principle of public-private partnerships embedded in the SDGs.

It’s not unexpected because businesses have always existed to create value – but what constitutes value continues to evolve. Where once it was narrowly measured in terms of pure profit, in recent decades this broadened to measure total shareholder return.

Today there is an emerging recognition that companies’ license to operate depends on an implicit contract with society. Value increasingly reflects a more holistic view incorporating the full financial, social and environmental impacts of a business, from sourcing to production to disposal. And recognises that supply chains are responsible for 90% of companies’ environmental impact.

The ambition to do more on sustainability is a common theme of my conversations with clients. But they are often held back by the practicalities of doing so at scale. There’s clearly a long way to go, which is why business, policymakers and regulators must collaborate and coordinate action to address two challenges.

The first is measurement. A broader definition of value creation demands improved measurement. HSBC’s survey shows businesses are frustrated by inconsistency in environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria.

There is a consistent gap between indicators companies’ state as relevant and those they measure. Common frameworks and standards can unleash action. Greater alignment in how companies report would enable peer comparison. The resulting competitive pressure can drive progress.

Greater transparency and measurement would also help address the second challenge: finance. It is identified as the largest barrier to becoming more sustainable. An additional annual investment of around $ 2.5 trillion is required to meet the UN goals. Banks can act as a catalyst for action through enabling large corporates to deliver sustainable outcomes in their supply chains.

SDG linked financing can also unlock new capital. HSBC launched the first SDG bond in 2017, with proceeds ring-fenced for projects aligned to seven selected goals. Followed in 2018 by the world’s first SDG sukuk, a sharia compliant bond. This reflects a significant turn towards sustainable investment, which already tops $ 30 trillion.

If business value increasingly reflects return to society, it follows that these wider societal factors will inform financing decisions. Efforts to improve the disclosure of risk relating to climate change across the financial system indicate a clear direction of travel. In time I believe an SDG performance factor will inform financing decisions and this will further accelerate the trend.

With a majority of businesses recognising their role in meeting the SDGs, what of the laggards? In the short term, companies are exposed to risk as society, regulators and competitors are increasingly alive to these issues.

Longer term they could be missing out on business opportunities too as achieving the UN goals could unlock $ 12 trillion in new market value and create 380 million jobs.

Change is often gradual, then sudden. As engagement rapidly spreads from school-age activists around the globe to the boardrooms of the UK’s largest companies, this feels like one of those moments.

It will be those business leaders who adjust their purpose accordingly, and account for societal impacts across their supply chains, that will generate sustainable value over the long term for all.

(The writer is HSBC’s Global Head of Trade and Receivables Finance.)