Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Monday, 10 September 2018 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ajith Nivard Cabraal

Central Bank Governor Dr. Indrajith Coomaraswamy recently stated that the Central Bank is to soon raise $ 250 million through the issuance of Panda Bonds. Such funds would be in addition to the Syndicated Loan of $ 1,000 million that it has already raised recently through the China Development Bank.

Sri Lanka’s Public Debt was at a value of Rs. 7,391 billion as at end 2014. Of such sum, the loans from China amounted to approximately Rs. 585 billion ($ 4.5 billion), or 8% of the total. At the same time, the Debt to GDP was at a manageable 71%, (down from 91% in 2005) and the interest cost in 2014 was Rs. 443 billion or 4.2% of GDP.

Sri Lanka’s debt related relevant data as at the end of 2014 would confirm that there was no truth whatsoever in such the suggestion that Sri Lanka was in any “Debt Trap” at that time:

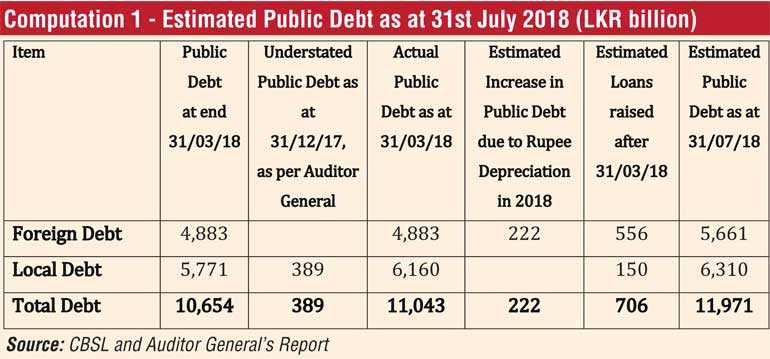

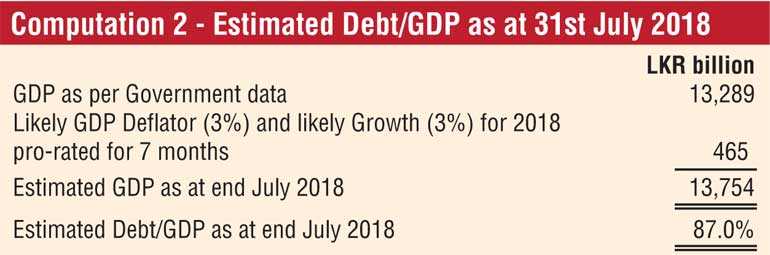

However, by end July 2018, Sri Lanka’s Public Debt had zoomed to around Rs. 11,971 billion (Please see Computation 1); a staggering increase of 59% in just three and half years, while the interest cost for 2018 is estimated at Rs. 820 billion, or nearly double that of the 2014 interest cost. The Debt to GDP ratio as at 31 July 2018 has also reached an alarming level of 87.0%. (Please see Computation 2).

However, by end July 2018, Sri Lanka’s Public Debt had zoomed to around Rs. 11,971 billion (Please see Computation 1); a staggering increase of 59% in just three and half years, while the interest cost for 2018 is estimated at Rs. 820 billion, or nearly double that of the 2014 interest cost. The Debt to GDP ratio as at 31 July 2018 has also reached an alarming level of 87.0%. (Please see Computation 2).

Further, according to the publicly available information, the Government’s total external debt had also since increased by a massive 33%: From $ 23.7 billion at end 2014 to at least $ 35.4 billion by July 2018, of which, International Sovereign Bonds which are mainly held by US and Western investors, now account for about $ 11.6 billion.

This Debt escalation has taken place in an economy that has recorded a serious declining GDP growth rate; from a healthy average of 6.4% from 2010 to 2014 to a dismal 3.1% in 2017. The GDP growth rate for the first half of 2018 has also not shown any signs of recovery, and key sectors such as construction have experienced significant negative growth. Accordingly, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka has reduced its 2018 GDP Growth projections to under 4%, although most analysts now expect it to be considerably less than 3%.

In the meantime, the country’s external trade deficit has ballooned substantially from $ 8,287 million in 2014 to $ 9,619 million in 2017. The Central Bank’s press release on 27 August 2018 reported that the trade deficit for the first half of 2018 had widened to $ 5,709 million as against $ 4,751 million in the first half of 2017, reflecting the continued worsening of the trade deficit owing to sluggish growth in exports and double digit increase in imports. On that basis, the trade deficit is likely to reach a massive $ 11,000 million this year. Workers’ Remittances too, which has been a major source of financing the current account deficit of the balance of payments has recorded only a sluggish increase of 0.9%.

In financing the current account deficit in 2018, the Government is reported to have so far raised a sizable $ 3,838 million: Of which $ 2,500 million has been from International Sovereign Bonds, $ 1,000 million has been from a China Development Bank Syndicated Loan, and further Forex loans of $ 338 million. But, sadly there has been no noticeable foreign direct investment this year, other than the final tranche of the one-off sales proceeds relating to the alienation of the Hambantota Port to China. Incidentally, the Debt incurred by Sri Lanka for the construction of the Hambantota Port was $ 1,322 million (or about Rs. 158 billion), and such Debt was only about 2.1% of the Total Debt of Sri Lanka as at the end of 2014. Hence, by no stretch of imagination could it also be claimed that the Sri Lankan Government was in a “Debt Trap” due to the Hambantota Port loan.

The level of gross official reserve assets of the country has also declined to $ 8.4 billion at end July 2018 from $ 9.3 billion by end June 2018. At the same time, the short term net drain on foreign currency assets between September and December, are also expected to be as high as $ 7.7 billion. In fact, considering the erosion in the balance of payments surplus in the first half of 2018 and the likely strain on the trade deficit and lower remittances inflows, the external reserve assets are likely to erode even further.

Reflecting these weaknesses, the LKR has rapidly depreciated by more than 5% this year to 163.00 per US Dollar, from a value of around 131.00 at the end of 2014: an unprecedented depreciation of about Rs. 32 per USD in just three and half years.

Adding to these woes, the exchange rate is likely to face even more pressure in the background of the crisis in Iran and Turkey, the fall in Sri Lanka’s debt-financed reserve assets, the Government Securities market mass-scale foreign investor exodus, and the wide-spread Equity sales by foreigners in the Colombo Stock Exchange. Further, the massive depreciation of the currency is now placing a very heavy burden on the national budget due to the sharply rising debt servicing cost and is likely to well exceed the budgeted interest cost of Rs. 820 billion, by a considerable margin.

As a result of these looming financial uncertainties, Moody’s have already warned of the acute financial risks in Sri Lanka, including the growing risks in the country’s banking and financial system, which is suffering from a high level of non-performing loans. Bloomberg too has ranked Sri Lanka among the highest risk countries for investors in early January 2018.

It is now clearly evident there has been a serious deterioration of the Debt Dynamics of Sri Lanka over the past 3½ years. It is also clear that such outcome is primarily due to the present Government’s unsound economic management, reckless borrowing, imposition of unbearable taxes and severe discouragement of investors. Consequently, the Sri Lankan Government’s debt situation has now reached a precarious and dangerous level.

In that background, if the Government were to borrow further by issuing more Forex debt in the form of Panda Bonds, it would lead to more reckless spending by the Government and precipitate a possible debt default.

Accordingly, as a former Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka for nearly nine years, during which period the Sri Lanka Economy grew from $ 24 billion to $ 79 billion, I urge the Government not to increase its Forex borrowing any further, as that would expose Sri Lanka to debt levels beyond the current debt to GDP level of nearly 87.0% (Please see Computation 2), and pave the way for Sri Lanka to be firmly entrenched in the category of Highly Indebted Countries.

(The writer is a former Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)