Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 19 August 2017 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Despite the monsoon making the work risky, two dredgers are digging and ferrying sand 24 hours a day for the new Colombo Port City construction site. On land, tight security and vehicle checks are in force at site gates near Colombo’s bustling central business district.

Despite the monsoon making the work risky, two dredgers are digging and ferrying sand 24 hours a day for the new Colombo Port City construction site. On land, tight security and vehicle checks are in force at site gates near Colombo’s bustling central business district.

Colombo Port City is Sri Lanka’s biggest foreign direct investment project ever. It is also China’s biggest investment yet in the Indian Ocean island nation, and a flagship part of its Belt and Road Initiative – a new port along the ‘Maritime Silk Road’.

Prestige project

Since work started here three years ago, the project has weathered a change of government that halted work for a year, and protests from environmentalists and fishermen.

The presidents of both countries – China’s Xi Jinping and Sri Lanka’s then-leader Mahinda Rajapaksa – watched the construction begin in September 2014.

Official estimates of total direct investment are $1.4 billion, which is expected to spur a further $13 billion in secondary investment. The port city is a joint project between China Communications Construction (CCC) and Sri Lanka Port Authority.

Built on sand

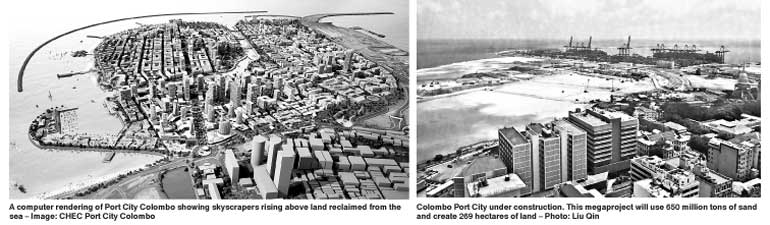

Controversies centre on the land that will host this international financial centre with its malls, hotels, high-rise homes, schools and hospitals. All of it will be reclaimed from the Indian Ocean.

The new port and city is a megaproject that will expand Sri Lanka’s current biggest city and commercial hub by 269 hectares, roughly the size of central London. Officials say it will create more than 83,000 jobs and house 270,000 people.

Sri Lanka’s Government has high hopes for this new city.

It calls it “Sri Lanka’s Hong Kong”, signalling its desire for a regional and global financial centre located midway between Dubai and Singapore.

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has told Chinese media that the project will be a special commercial and financial zone, with its own financial and judicial systems to ensure it runs efficiently.

Electoral politics

But Wickremesinghe was not always so positive. He campaigned for election on a promise to tear up the project agreement – echoing the concerns of environmentalists and fishermen over the impact of large scale dredging on fish stocks and coastal erosion.

His Government ordered work halted in March 2015, only six months into construction.

Development Strategies and International Trade Minister Malik Samarawickrama said the project lacked a full Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): “In opposition we did request the government of the time publish the relevant environmental reports, but got no response,” Chinese website Caixin cited him as saying.

Unlike in China, land in Sri Lanka is privately owned so forced relocations, such as those to clear land for the Beijing Olympics venues, are harder and meant building over parts of the existing city of Colombo was not an option.

Instead, land is being reclaimed from the ocean. Halting the work caused daily losses of $380,000. The Chinese side requested compensation, which the Sri Lankan side offered to pay with an extra 36 hectares of reclaimed land, bringing the total area of land created to 269 hectares.

The result is even more dredging. Land reclamation and construction are expected to swallow 650 million cubic metres of sand in total.

According to Sri Lankan newspaper the Daily Mirror, Sajeewa Chamikara, Spokesperson for the Sri Lankan environmental group Environment Conservation Trust, predicts dredging will damage Sri Lanka’s marine ecosystems and coastline.

Sri Lanka has already lost 85 square kilometres of land to coastal erosion.

Dr. Ravindra Kariyawasam, of the Centre for Environment and Nature Studies campaign group says the port city will exacerbate coastal erosion.

Dredging along the rim of the famous Negombo Lagoon may damage the rocks that form its foundations, says Aruna Roshantha of the All-Ceylon Fisheries Union.

China Communications Construction has responded by saying it undertook four years of preparatory work before signing the agreement with the previous administration and that all of it was carried out according to Sri Lankan regulations. It added that a third-party body had conducted the environmental impact assessment.

On 9 March 2016, Sri Lanka’s Cabinet approved a supplementary environmental impact assessment report on the project, submitted by the Central Environmental Authority.

The report rebutted various complaints about the port city’s environmental impact and cleared the way for work to restart.

But according to Chamikara, Sri Lankan law does not allow for any such “supplementary” report.

A local Catholic priest and staunch opponent of the project Rev. Fr. Sarath Iddamalgoda says people will continue to protest until construction is halted for good.

Missing money

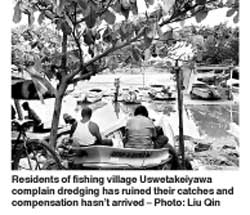

While the Government aspires to create a global financial centre, local fishermen are angry about the project’s impact on their livelihoods.

In Uswetakeiyawa, a nearby fishing village, questions quickly drew a crowd. Fishermen who had been mending their boats pointed to the dredging ships. “Do you see, the Chinese company’s dredgers are working 24 hours a day? There’s no way for us to fish, we can’t make a living,” said one.

Fish are scared off and nets are often damaged by dredgers. Over 1,000 households here rely on fishing, and the incomes of around 10,000 fishermen on the Negombo coast have been affected by the dredging there, according to the fishermen.

“Originally they said they’d only work 10 kilometres offshore, now they’re only 7.5 kilometres away,” said one fisherman who declined to be named.

An official with the Chinese partner told a Caixin reporter the Sri Lankan Government had agreed to change reduce the dredging limit because sand was scarce further out to sea. Fishermen were consulted, the official said.

Those that chinadialogue spoke to complained furiously of being cheated for votes: “We supported the new Government because they said they’d cancel the project, but once they’d got our votes they just let it start up again.”

They say none of the Rs. 100 million ($652,802; 4.3 million yuan) in compensation that CCC has already paid via the Sri Lankan fisheries authorities has come to them.

One 50-year-old fisherman complained, “All we’ve got is hunger and anger. Those politicians pocketed all the compensation.”

The Chinese firm has pledged the overall compensation package will eventually be worth 500 million rupees ($3.2 million; 22 million yuan), channelled through the Sri Lankan fisheries authorities, as cash subsidies, insurance and a new fish processing plant.

Chinese firms face risks

Since the Cabinet approved the supplementary EIA report and construction resumed, the Sri Lankan authorities are once again keen to attract Chinese investment.

Surath Wickramasinghe, an architect and chair of the Sri Lankan Chamber of Construction Industry, says any firm that can help Sri Lanka develop – whether Chinese, American, Japanese or Indian – will be welcome.

He enthused that China’s Belt and Road Initiative is prompting many more Chinese firms to look for opportunities in Sri Lanka; one recent delegation was made up of 50 companies.

But for Chinese firms, Sri Lankan politics are a real risk. The year-long suspension on the port city was not the only one. The new government’s arrival meant similar stoppages for other Chinese-funded projects that year.

One project official with CCC, who did not wish to give his name, said, “Changes of government are very frequent and there’ll be another election in 2019. It’s a race against time for us now, doing everything we can to get the project finished as soon as possible.”

“A change of government is a real risk,” Jin Jiaman, Executive Director of the Global Environmental Institute, told chinadialogue. “US politicians like to turn on China during an election, but now we’re finding China is a visible target during elections in many other nations too – it’s a trend we need to be wary of.”

(Source: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9985-Sri-Lanka-s-new-Hong-Kong-project-risky-for-all-sides.)