Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 22 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shenella Fonseka

By Shenella Fonseka

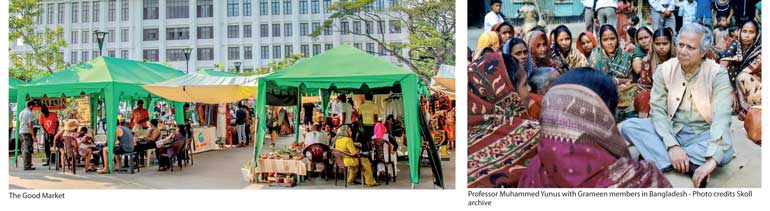

http://vesess.com: A few years ago, a friend asked me, “Shall we meet at The Good Market?” At the time, The Good Market was a very new event, and no one knew much about it except that it would happen every Saturday at the Race Course Car Park.

I didn’t want to appear ignorant of this seemingly cool place, so I had to do my research as to where this ‘Good Market’ was happening. I found out the details, and went. I was truly mesmerised. The place was full of many novel ideas, things I never imagined would be available so freely in Sri Lanka. The ‘polos cutlets’ and the ‘narang popsicles’ were an absolute treat, and after that first experience, The Good Market became a weekly outing. I don’t speak for myself alone, but for most of my generation.

However, what matters is that three years ago, I did not have a clue as to what it was or what its purpose was (though in my defence, most of us didn’t). Surprisingly and yet sadly, I had never heard about it (preoccupied as I was with the nearly futile task of trying to secure my place at a State University), until a friend of mine was employed by The Good Market and introduced me to the term ‘social entrepreneurship’. That sparked my interest in the concept.

The ignorance so many of us experienced regarding such social entrepreneurship was not entirely the fault of any one individual. Why do I say that? Because ventures such as these, more often than not, operate below the public radar, and there is an evident lack of initiative on the part of the Government to take socially profitable ventures to the public.

Although social entrepreneurship is a concept that has been around for a while, only recently has it become popular in Sri Lanka. Social entrepreneurship can be simply defined as a venture which takes up a social problem with the aim of transforming it.

A social entrepreneur uses the principles of entrepreneurship with the primary intention of creating social capital, not profit. Social entrepreneurship is open to a wide variety of business ideas, ranging from small village co-operatives to large-scale businesses.

Nobel Peace prize laureate Professor Muhammed Yunus is considered as a pioneer of social enterprise because of his novel social innovation of microfinance, as shown through Grameen Bank, which serves more than half the population of Bangladesh.

Yunus opines that people working in such socially-based enterprises get a ‘feel-good’ reward on top of their salaries. “Even shareholders start enjoying it,” he says. “They don’t mind earning a little less if it is helping the children of the country, or poor people, or single mothers. They are proud that their company is taking care of that.”

It is of great importance that the youth of the country are motivated to enter into the field of socially based business, and Yunus further states that he believes these youth “should learn that there are two kinds of businesses in the world. One is a business which makes money, and the other solves the problems of the world.”

A rather prominent criticism levelled against social entrepreneurship in Sri Lanka is that profit-making organisations cannot effectively solve social problems. The perfect explanation for why this is not the case lies in the statement made by Dr. Faiz Shah, Director of the Yunus Center, Asian Institute of Technology (Bangkok) at Sri Lanka’s recently-concluded International Conference of Social Entrepreneurship 2017 (ICSE).

Shah affirmed that social enterprises are different from charities. This he equated to the announcement made prior to every flight departure: “Please secure your own oxygen mask before assisting others”. A social enterprise must be capable of surviving as a business in order to offer aid to the community.

The aim of a social enterprise is to assist the common good as a self-sufficient and self-sustained enterprise. It is thus classified as part of the private sector and can be considered a competitive business reinvesting its profit for social purposes. Hence it is vital that such enterprises are competitive and profit-making.

Many countries are adopting the social entrepreneurship model and reaping many benefits from it. Not only does it aid the social sector, it boosts the economy and creates a proactive and socially concerned young generation of entrepreneurs as well. Therefore, many nations aim to incentivise the startup of social enterprises because it directly aids in the role of the government to maximise social utility. France is a leader in this aspect.

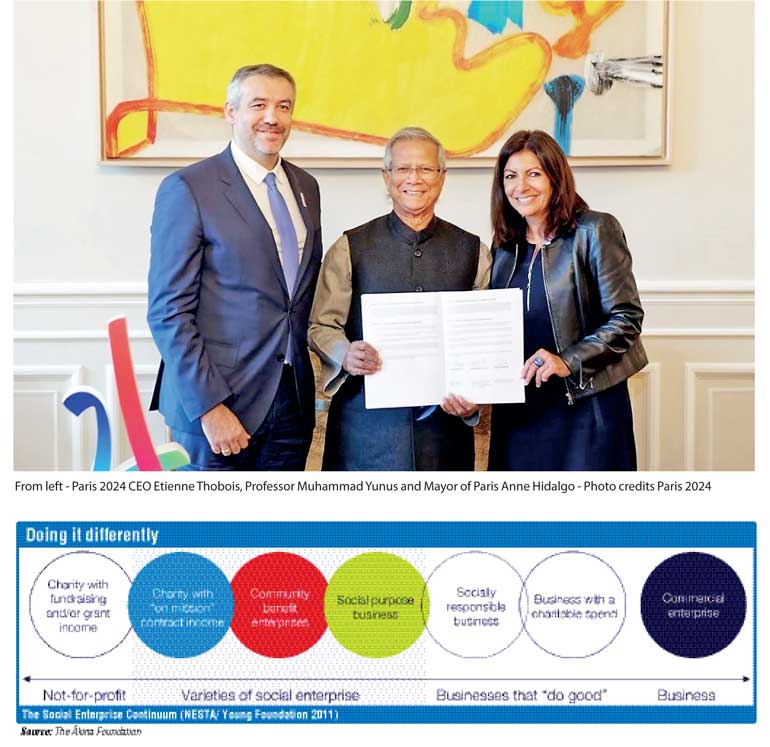

The Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, has professed that one of her primary aims is to make her city a hub for social entrepreneurship. She hopes to make it a central feature of the 2024 Olympics, in the event that Paris wins the bid. Most developed and developing countries in the world have adopted various methods to encourage and harness the growth of these socially based enterprises.

The UK has been considered a forerunner in this field, employing more than two million people and contributing more than £55 billion a year to the UK economy. Schemes such as the Social Enterprise Development Awards recognise the most successful of these enterprises, granting cash prizes and other types of support. Further, financial assistance such as social impact bonds are granted and tax relief concessions have been created for investors in social enterprises.

In the United States too, many schemes and frameworks are now in place to incubate social enterprises. These range from removing regulatory barriers to unlock private-impact investments to creating awareness and supporting such investments. So if all these countries have recognised the importance of these enterprises, one question remains. Why has the Government of Sri Lanka completely failed to identify these enterprises given that they serve the purpose of solving social problems?

Many misconceptions exist about the fundamentals of social entrepreneurship. This maybe owing to the general lack of awareness about the subject matter, as well as the fact that these businesses are not yet recognised as ‘doing good’ by relevant authorities – although there is plenty of evidence for this. Certain organisations have been identified for their exceptional work in the private sector, but it is a lesser-known fact that some of them are classified as social enterprises.

For example, the Sarvodaya Movement, initiated by Dr. Ariyaratne, was a sizeable and significant social innovation at the time. As another example, Bhagya Wijayawardane was given the Queen’s Young Leader Award for 2018, an award established by Queen Elizabeth II. It is ironic that the social entrepreneurs of Sri Lanka are being recognised for their achievements internationally, and yet not in their own homeland which they serve.

Bhagya was recognised for her spectacular leadership skills and for making a difference in improving other citizens’ lives through her organisation, ESHKOL. In an exclusive interview conducted by me with this young social entrepreneur, she opined: “It isn’t easy to give up on other career prospects and pursue a common goal.” However, she rose to the cause despite this barrier.

In her opinion, what is lacking in our country is a regulatory framework assisting and supporting budding social entrepreneurs such as herself. She believes that three things are necessary to harness the momentum of the social entrepreneurship sector: creation of public awareness, implementation of preferential tax policies for entrepreneurs and investors, and provision of an inclusive educational path for budding entrepreneurs by partnering with local incubators and universities.

Despite the general public’s lack of knowledge, the enthusiasm shown by the social entrepreneurial community of Sri Lanka is considerable. These energetic and passionate individuals have shown much dedication and commitment to their cause.

Mario De Alwis, CEO of Social Enterprise Lanka, has spoken about his experience as a social entrepreneur and what motivated him to move back to his homeland Sri Lanka from Australia. “I understood how this concept was being used globally to solve social and environmental problems, and it wasn’t being promoted appropriately or identified by the Government in Sri Lanka. This drove me to move back home and join Social Enterprise Lanka.”

With its telecasting of Ath Pavura and introducing social enterprise as a course unit at the Open University and in other ventures, Social Enterprise Lanka has been doing more than its fair share towards creating awareness and gaining recognition by the Government.

A secondary issue is that Sri Lanka’s educational method prepares students to be job seekers rather than job makers. This creates a reluctance within the work force to join social enterprises. Students and undergraduates primarily intend to be employed by the public sector, and a minority would be satisfied with the private sector. However, this is only a matter of perception and mindset. What must be promoted is entrepreneurial skill, and the idea that an individual can be an employer rather than an employee.

Kinley Dorji, Secretary-General of the Colombo Plan, said while speaking at ICSE that if social entrepreneurship was advocated in the country, “instead of the youth seeking jobs, they can create jobs”. This would not just promote social entrepreneurship, but also solve an issue faced by the country’s economy—unemployment.

However, the primary problem is clear. In my opinion, the reasons for the stunted growth of social entrepreneurship field boils down to one main reason: the fundamentals of the concept of social entrepreneurship being misunderstood by the masses due to the lack of awareness on the subject matter.

This is mainly due to the ignorance of the general public fuelled by the little or no attention paid to these enterprises by the government. This affects the entrepreneurial community as well as investors. When investors lose the incentive to make an impact (as the government does not grant them any preferential tax schemes or tax holidays), entrepreneurs suffer directly due to the lack of funding.

The only plausible solution to the issue at hand, as identified by all my interviewees and most speakers at the ICSE, is governmental recognition of the efforts of social entrepreneurs and creation of awareness about it. It is in the hands of those in authority to identify the wealth of positive impact created by this group of entrepreneurs to the country as a whole.

The number of initiatives and ventures that have come about under the social enterprise umbrella are countless, and all serve a worthy cause. The government has so far made no advancements in this area, although the initiative to popularise the concept of social entrepreneurship began many years ago.

The valiant efforts of these activists/entrepreneurs have failed on numerous occasions. The most recent was a group of social entrepreneurs including Dr. Lalith Welamedage, Co-Founder and Managing Director/CEO of Lanka Social Ventures, Dr. Amanda Kiessel, CoFounder of Good Market GTE Ltd., and Selyna Peiris, Director of Business Development, Selyn Exporters Ltd., who collectively proposed a series of recommendations to be included in the 2018 Budget.

Recognising social enterprises, as well as providing regulatory and legal frameworks, financial aids and incentives, preferential tax schemes and tax rebates are a few of the many recommendations these individuals have made. Despite these courageous efforts, the budget proposals for the coming year have remained silent about any matters concerning social entrepreneurship.

I strongly believe that the cause of social entrepreneurship must be advocated on all levels. What must be understood is that each and every social enterprise aims at solving a social problem of some nature, bringing our nation one step closer to achieving its sustainable development goals.

However, the greatest barrier to such an understanding stems from the public’s lack of knowledge and the ignorance of the authorities about these social enterprises and their mission. We mostly do things ‘just because’ others are doing it, which in turn leads to turning a blind eye towards enterprises that are committed to curbing issues faced by the society as a whole.

Hence, by implementing inclusive education pathways, incubation programmes for startup enterprises, preferential tax schemes and other legal and regulatory reforms, the ultimate goal of creating public awareness of and interest in social entrepreneurship can be achieved, thereby nurturing and creating a sustainable ecosystem for social enterprises.

(Source: http://vesess.com/social-enterprises/)