Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 26 October 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Gayani Hurulle

The Director General of the Department of Samurdhi released a circular on 29 August stating that monthly cash transfers to senior citizens, persons with disabilities (PWDs), and kidney patients must be administered through Samurdhi banks from September 2022. In practice, this will occur from October.

The Director General of the Department of Samurdhi released a circular on 29 August stating that monthly cash transfers to senior citizens, persons with disabilities (PWDs), and kidney patients must be administered through Samurdhi banks from September 2022. In practice, this will occur from October.

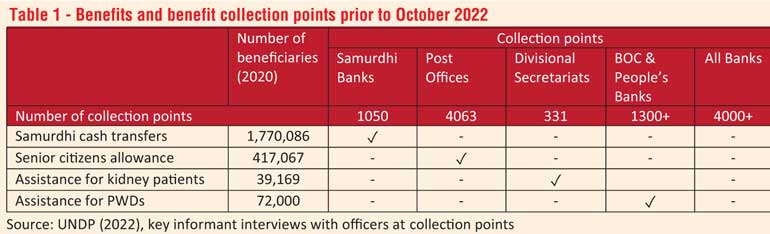

This disbursement mechanism deviates significantly from that used earlier, where each of these schemes had different collection points. Samurdhi banks were used exclusively as distribution points for the Samurdhi monthly cash transfers. Senior citizens’ allowances, PWD benefits and kidney patients’ allowances were disbursed via post offices, State banks and divisional secretariats, respectively (Table 1). There is a distinct lack of cohesion in the delivery mechanisms, a symptom of a broader issue – a fragmented social welfare system. So, streamlining delivery through a single channel looks like a good decision. While efforts to streamline delivery are commendable, giving a monopoly to Samurdhi banks is not the solution.

Samurdhi is inconvenient

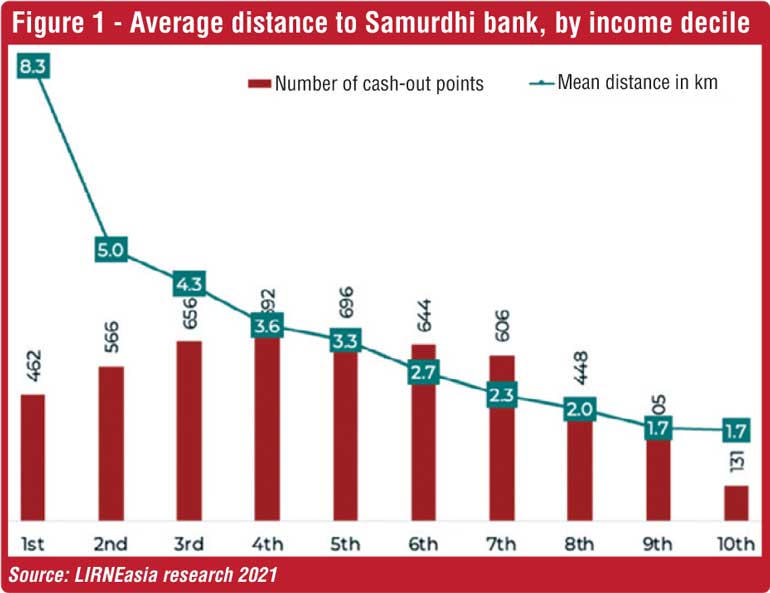

One reason not to centralise disbursements in Samurdhi banks is to save travel time and costs. At present, there are only around 1,050 Samurdhi bank branches. LIRNEasia’s research indicates that the poorest 10% of the population – those most in need of assistance – would have to travel 8.3 km on average to visit a Samurdhi bank. Because there are nearly four times as many post offices as there are Samurdhi banks, transaction costs will on average increase for the 400,000+ individuals receiving senior citizen’s allowances. This would certainly hold true for Kala* (name changed), a senior citizen from Jaffna, who lives a minute away from a post office. If she was to travel to Samurdhi bank, she would have to travel in a tuk tuk (due to physical accessibility concerns around bus travel) incurring a cost of Rs. 1,700 to collect a benefit of Rs. 1,900.

Samurdhi is inefficient

The distribution system within Samurdhi banks is inefficient. Ramani* (name changed), a Samurdhi beneficiary from Colombo District stated, “[My officer usually asks me to come into the Samurdhi bank] to collect benefits between 9:30 and 10:30 a.m. But the Samurdhi officer is in at different times. Then they need time to check their ledgers and ascertain our loans and arrears before making the monthly cash payment. We try to get our work done by 1:30 p.m. so that we can pick up our children from school. But it often takes a lot of time. On some days the officer is not in at the Samurdhi Bank, so we return home empty handed.”

The question then remains, what are the merits of increasing footfall to Samurdhi Banks by around 30% if they are ill-equipped to ensure efficient delivery even to current beneficiaries? There has been a push to digitalise internal systems, which is a step in the right direction in increasing efficiency. But until the processes are streamlined and rolled out at scale, and the officers gain the necessary digital competencies handle the system, overburdening it with three other schemes is unlikely to see the necessary efficiency gains. In fact, it will worsen the experience of all beneficiaries, including those currently wasting time for Samurdi payment.

Choice for recipients

Delivering benefits through regular (non-Samurdhi, state/commercial banks) can help. First, there are over four times as many collection points (branches through which withdrawals can be made and/or ATMs) as Samurdhi banks – this would translate to less travel time and costs for beneficiaries than the proposed system. The use of ATMs to collect benefits can potentially reduce waiting times too. LIRNEasia’s nationally representative survey from 2021 also shows that 70% of households receiving regular welfare benefits (e.g., senior citizens allowances and assistance for PWDs) have non-Samurdhi bank accounts, making it a viable option for a large proportion of the target group.

In a digitalised environment there is no reason to channel benefits through a single agency. Other collection points could be used alongside banks. Having multiple options can give the beneficiaries the autonomy and agency to decide which collection point is most convenient to them. The beneficiary could simply indicate their preferred collection point (e.g., bank or post office), and the relevant government institution could direct the funds there. We could follow the mechanism used when distributing state pensions, where pensioners can collect benefits from post offices, or have it deposited into any regular bank account.

The key here is to not become over reliant on Samurdhi banks, whose systemic flaws such as politicisation have been well-documented. We should instead focus on optimising for transparent processes, and ensuring that citizens are able to easily access these benefits. One hopes the circular is motivated by the desire to improve outcomes for beneficiaries and not by the need to strengthen the case for preserving the power exercised by 25,000 Samurdhi officers.

(The writer is a Senior Research Manager at LIRNEasia responsible for ongoing research on social safety nets.)