Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 5 February 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The discussion on State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) has commenced again with the release of a report by Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE). Add to this the recent comment of the Minister of Power that the loss incurred by the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) would be Rs. 80 b this year, and the release of Presidential Committee Report on SriLankan Airlines.

The excerpts by media on the COPE report state: “Mismanagement, irregularities, oversight, wastage, failure to take action on findings, high salaried employees and the need for media to be at COPE proceedings.” The extent of negativity makes one wonder whether the objective is to resolve the issues or to make it look as gloomy as possible for political benefit.

Understanding the status of SOEs

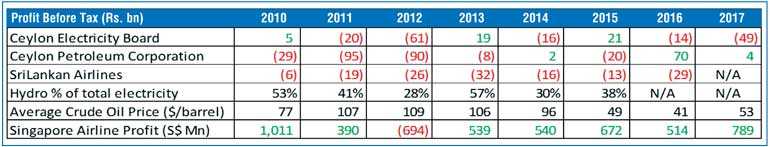

A key starting point for this discussion would be the scale and continuity of losses made by each SOE. Considering the sheer size and the duration in which losses have been incurred, it’s CEB, SriLankan Airlines and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) that need the closest attention (although CPC is making profits now, it could easily revert to high losses if crude oil price reaches anywhere near the levels seen in 2011-2013).

This is not to say that the other SOEs that are making lower losses are acceptable. But addressing the problem of SOEs practically would mean that one stops the flood gates first, before fixing the loopholes. When there are multiple substantial problems to be addressed at a national level by the country’s leadership, with limited resources, the uninterrupted focus should be on the bigger problems.

Further, on a cumulative basis, the SOEs are profitable at around Rs. 50 b p.a, although mainly due to the three State-owned banks. Even if one excludes the three State banks, the total profitability breaks even on a long term basis, with certain years recording profits while certain years incurring losses. Hence it’s not all gloom and doom.

Should every SOE be profitable?

In the case of SOEs, the non-financial strategic importance of each entity needs to be evaluated in understanding whether it is acceptable for certain SOEs to incur manageable losses. To put it another way, whether certain SOEs should be privatised or not.

CEB is the supplier of electricity to the nation and is of high strategic importance. The profit should not be the priority of such an entity (not big losses either), but the priority should be the reliable, uninterrupted supply and the ability to supply power at a reasonable cost to the consumer.

Both industries and corporates depend heavily on those factors and any deterioration on those fronts could directly affect Sri Lanka’s competitiveness in the global economy. Add to this is the complexity of the CEB and the powerful trade union. In this light, with Sri Lanka grappling with more serious problems, privatising of CEB should not even be in the agenda.

The CPC is the main supplier of fuel to the country and hence plays an equally important role in the county’s economic affairs. Hence State control here is vital so that at times of crisis (such as exceptionally high global crude oil prices that prevailed in 2011-2014), the entity does not operate on a rigid financial oriented objective, but rather a more practical and strategic role of shielding the local economy from a major global shock. Hence incurring losses at such scenarios should be acceptable.

Improvements for CEB and CPC

Having a glance at the financial performance of CEB, one could make two conclusions. Performance improves when there’s high rainfall which increases the utilisation of hydropower plants (2010 and 2013) and the importance of implementing low cost power plants.

The start of the Norochcholai Power Plant not only helped the financial performance in 2015 despite a poor utilisation of hydropower plants, but helped to reduce the electricity tariff by 25% for the consumers in the latter part of 2014. Hence the simple solution is to ensure the steady supply of lower cost power plants (coal, etc.) which would boost the performance of CEB.

The end objective would be to ensure CEB breaks even annually (on average) on a long term basis. The substantial profits in years of high rainfall would set off the marginal losses incurred in years of low rainfall.

As for CPC, it is clear that the major impact is from the global crude oil price. When the global price has been high, the domestic prices have been subsidised (understandably) resulting in financial losses (2011 and 2012). In fact, this has been probably aggravated by the delays in payments by CEB (to CPC). Hence a financially stronger CEB would automatically improve the performance of CPC. It would be important to ensure that CPC also breaks even annually (on average) on a long term basis. Hence it is important that when crude oil price falls, the CPC maintains a healthy margin and recovers the losses made previously. In other words, the pricing should be cost reflective in the long term (but may not be in the short term), so that the volatility is less for the consumer and pressure is less for the politician.

The case of SriLankan Airlines

Is the airline strategically important? Clearly it is less so than the earlier two entities. On one hand the impact on the economy is significantly less and there are many other alternative airlines available. But there are other factors such as the national pride, strategic support for key sectors such as tourism, national security, etc.

However there is a clear case for professional foreign management and even foreign ownership close to 50%. There is no justification for continued losses and there is no justification for subsidising at the cost of the taxpayer. Clearly SriLankan Airlines had a good arrangement with Emirates which was terminated just before the global industry went into turbulence due to high global fuel prices. Even top global airlines struggled as seen by the financial performance of Singapore Airlines from 2011-2013.

Leaving the past behind, and the clear data over the last nine years, the way forward could be to re-enter a foreign collaboration and improve the management so that there wouldn’t be a need for taxpayer bailout in the future. For such an initiative to succeed, the balance sheet needs to be improved. With an accumulated loss of Rs. 170 b as at March 2017, it would be difficult to convince an attractive international party.

Therefore it would be necessary for the Treasury to infuse capital to eliminate substantial part of the accumulated loss and move forward. After all, it’s a sunk cost which has been already incurred. Fretting over that would just inflate that loss as we have seen clearly up to now (accumulated loss was Rs. 128 b in March 2015). The total loss would possibly reach around Rs. 250 b by March which highlights the fact that if this measure was implemented few years ago, the burden on Treasury would have been so much less. But better late than never.

(The writers could be contacted via [email protected].)