Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 10 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) issued the following statement yesterday in response to the article titled ‘Government and CB have abdicated vital statutory duty by not being able to deal with rupee depreciation’ by former Central Bank Governor Ajith Nivaard Cabraal which was published in Daily FT on 8 October:

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) issued the following statement yesterday in response to the article titled ‘Government and CB have abdicated vital statutory duty by not being able to deal with rupee depreciation’ by former Central Bank Governor Ajith Nivaard Cabraal which was published in Daily FT on 8 October:

The Central Bank is statutorily charged with the responsibility of securing, so far as possible by action authorised by the Monetary Law Act (MLA), a) economic and price stability; and b) financial system stability, with a view to encouraging and promoting the development of the productive resources of Sri Lanka.

While financial system stability is identified by the resilience of the financial system to internal and external shocks, price stability is generally defined as maintaining low and stable inflation, which leads to economic conditions that support high and sustainable levels of economic growth.

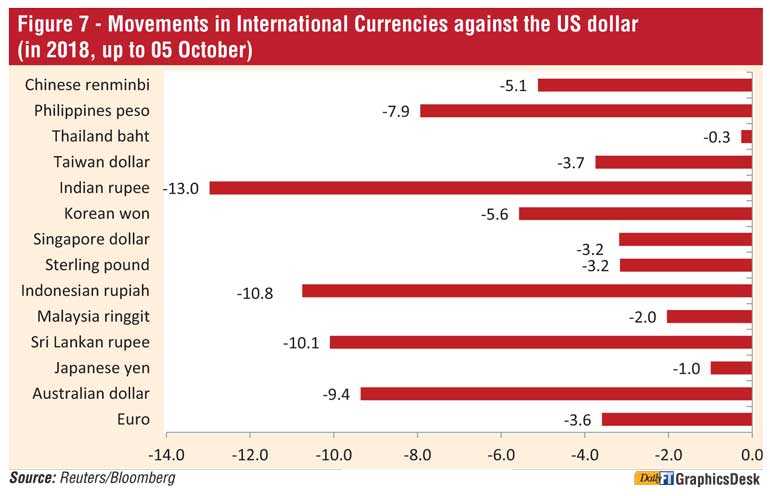

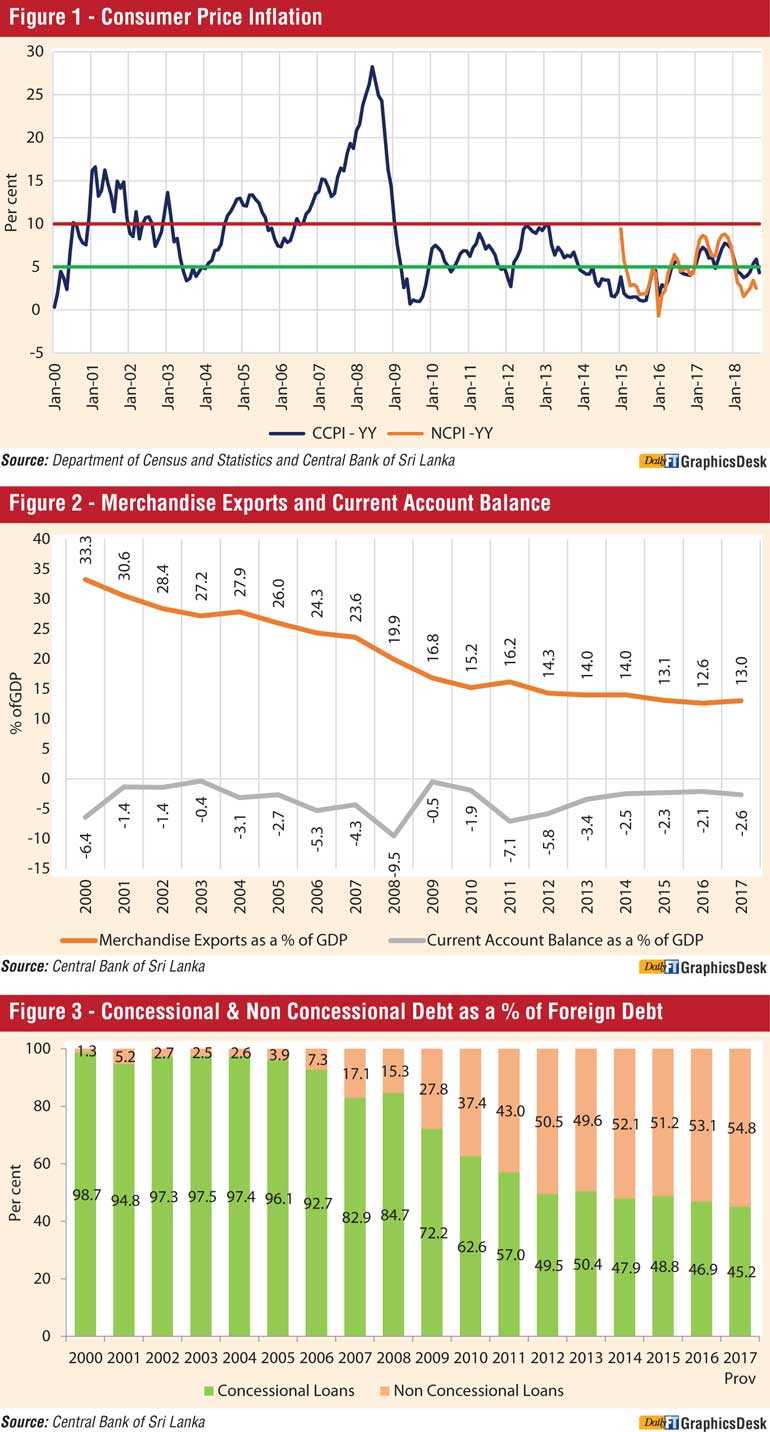

Historical data on inflation (Figure 1) shows that, unlike in certain periods in the past, inflation has been maintained at single digit levels for a continued period of almost 10 years, suggesting that the Central Bank has been more successful in carrying out its statutory responsibility of maintaining price stability in the recent past.

While it is expected that this will reduce uncertainties in the economy and support high economic growth in future, the ongoing efforts to introduce flexible inflation targeting as Sri Lanka’s monetary policy framework will enable the Central Bank to maintain inflation at mid-single digit levels on a sustainable basis.

With regard to the exchange rate and reserve management, the Central Bank operates with a macroeconomic view, and the bank’s considerations in this regard include the possible impact on domestic price stability through imported inflation, the currency’s external competitiveness, developments in the global economy and the adequacy of international reserves to meet the obligations of the Central Bank, the government, banking institutions and other persons in Sri Lanka.

As Section 65 of the MLA itself identifies, Sri Lanka’s exchange arrangements are expected to be consistent with the underlying trends in the country. The movements of Sri Lanka’s export earnings as a percentage of GDP and the external current account deficit as a percentage of GDP (Figure 2) show that the pressure on the exchange rate emanating from underlying economic trends in the country have been persistent, with little effort to address such unfavourable trends throughout history.

In the past, the Central Bank has intervened in the foreign exchange market to stabilise the exchange rate as well as to build up reserves. For instance, in 2009, with the positive investor sentiment following the end of the internal conflict, the Central Bank was able to absorb US dollars 3,122 million on a gross basis from the market, while in 2017, the Central Bank purchased US dollars 2,214 million. In contrast, during 2011, 2012, 2015 and 2016, the Central Bank has supplied to the market US dollars 3,184 million, US dollars 1,797 million, US dollars 3,429 million, and US dollars 1,900 million, respectively, on a gross basis. In spite of these interventions, the rupee depreciated by 10.4% in 2012 and 9% in 2015 (Table 1).

However, the Central Bank has increasingly realised that efforts to artificially stabilise the exchange rate extensively by supplying foreign exchange out of its official international reserves have only worsened Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic conditions and medium term prospects. Propping up the exchange rate through intervention makes imports artificially cheaper, contributing to a continued widening of the trade deficit and leaving the country vulnerable to exogenous shocks.

Moreover, the loss of reserves due to such intervention has been replenished mostly by commercial borrowing including the issuance of International Sovereign Bonds (Table 2). As a result, the share of non-concessional borrowing within the stock of foreign debt has increased from 1.3% in 2000 to 52.1% in 2014 and 54.8% in 2017 (Figure 3).

In addition, benefitting from the global low inflation environment, Sri Lanka observed net foreign investment inflows to the government securities market during 2009-2013 amounting to US dollars 3,375 million, and a substantial portion of these inflows was also absorbed into the official international reserves (Table 3).

In line with increased foreign currency borrowing, including the issuance of International Sovereign Bonds, the annual foreign currency debt service obligations of the Government have also increased considerably over time. This is also a key consideration that is factored into the Central Bank decisions with regard to foreign reserve management, and the Central Bank endeavours to maintain a higher reserve coverage by maintain a higher level of reserves than earlier.

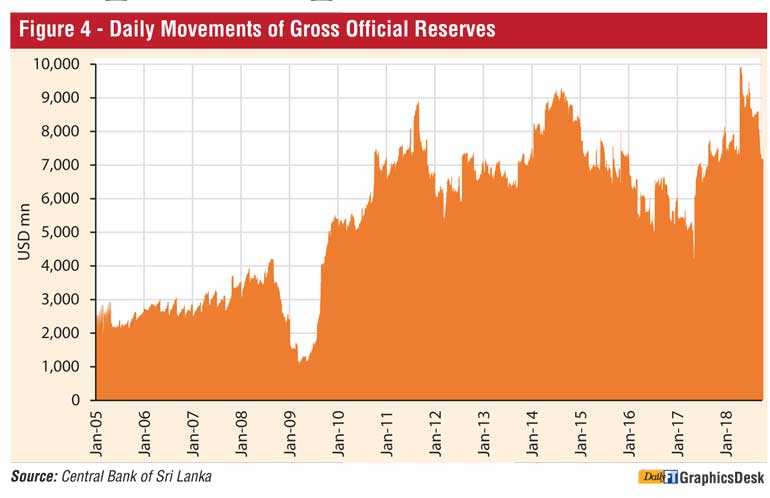

In the meantime, it must be noted that the amount of gross official reserves vary on a daily basis, primarily based on the transactions of the government and the Central Bank (Figure 4). The reported decline of official reserves to US dollars 7.2 billion at end September 2018 is also expected to be temporary, and reserves are projected to increase with the expected receipts in the period ahead.

However, had the Central Bank intervened in the foreign exchange market and supplied foreign exchange in large volumes as in 2011/12 or 2015, official reserves at the end of September 2018 would have been much lower, which could have posed a serious concern for investors. Therefore, the exchange rate and reserve management strategy adopted by the Central Bank during the latest episode of currency pressure is consistent with the objective of maintaining economic and price stability.

Unlike in the past where reserves were allowed to decline through foreign exchange sales by the Central Bank in the domestic market to finance imports, the downward movements in reserves are now closely related to meeting Government’s debt service requirements, including the servicing of and meeting maturing commercial debt obligations. This is a statutory duty of the Central Bank, which has necessitated a more prudent approach to reserve management than in the past.

Furthermore, the global market conditions that were favourable for emerging market and developing economies following quantitative easing by major economies have reversed notably in the recent past. As shown in Figures 5a and 5b, emerging market bond and equity flows have slowed significantly. Figure 6 shows the recent rise in global interest rates, which is also a notably unfavourable development for emerging market economies that had access to cheap and readily available access to global financial markets in the period after 2009.

As a result of these changing global market conditions, the emerging market economies, particularly those with deficit current account positions, have faced depreciation pressure in the recent past. Argentina and Turkey have experienced severe year-to-date currency depreciations of 51% and 39%, respectively. Currencies in South Africa, India, Brazil, Russia, Uruguay, and Indonesia have depreciated by 10-20% year-to-date, compared to Sri Lanka’s year-to-date depreciation of 10%. During 2018, up to end September, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s intervention amounted to only USD 185 million on a net basis, as opposed to heavy intervention in several of the countries mentioned above.

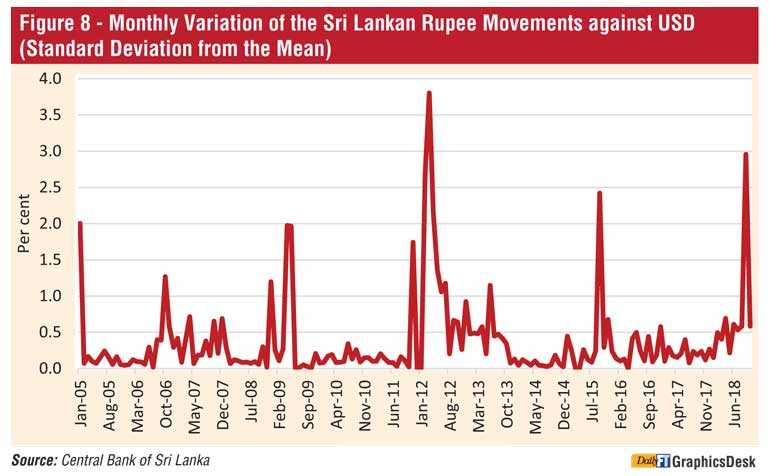

In addition, in spite of the current unfavourable global market conditions, the Sri Lankan rupee appears to be less volatile than observed in some periods in the past (Figure 8). In particular, volatility of the exchange rate during the year 2012 as captured by the standard deviation of the daily exchange rate was at 5.98%, compared to the volatility of 3.88% observed thus far in 2018.

In view of the above, the allegations in the said article that the Central Bank has neglected its statutory duty and the recent depreciation of the rupee could have been better managed are misleading. The exchange rate pressure that is currently observed is not limited to Sri Lanka, and any attempt to reverse such developments by supplying large amounts of foreign exchange from official international reserves would only lead to an adverse outcome. Instead, the Central Bank has allowed market forces to determine the overall trend of the exchange rate, while intervening when essential to curb excessive speculation on the exchange rate.

Meanwhile, the Central Bank and the government have already adopted a number of short term prudential and fiscal measures to contain the pressure on the exchange rate. However, the long term solution to the matter of the exchange rate lies in addressing the persistent current account deficits through encouraging the production economy and merchandise and services exports.