Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 12 December 2019 01:26 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

|

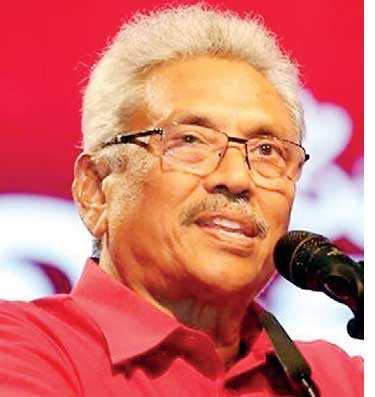

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa |

Prime Minister and Finance Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa |

By M. Hakim Usoof

It is praiseworthy to note the strict selection criteria for heads of State agencies implemented by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s new administration. This is the first time in the history of our country that individuals to key positions are being appointed on the basis of their professional competence and capacity, which is a vital change, as State-owned Enterprises (SOEs) are run inefficiently owing to their inefficient management by political appointees.

Political affiliation to the ruling party was the overriding criteria that prevailed until 16 November 2019 when selecting people to the governing bodies of State organisations in our country. Clearly, these business enterprises have not been performing to their full potential due to the absence of good governance, clear accountability mechanisms, performance-based incentive schemes and a strong supervisory role played by SOE management. SOEs are often claimed to be less profitable and less efficient than private entities. SOEs are less efficient and have lower profitability compared to private entities due to the soft budget constraint behaviour and policy burdens imposed by the State.

SOEs in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is a country which has had a large State sector for decades. Currently, Sri Lanka has about 400 SOEs, according to the Treasury, with over a million employees, which in 2018 made an aggregate loss of $ 27 billion. This is nearly one-third of the country’s GDP. These are largely seen as employment providers rather than service providers. But they do consume an extraordinary amount of resources and possess impressive assets.

Focus of the State

In most developing countries, State ownership is geared towards strategic sectors — either sectors that are crucial for economic development or ones that control the natural resources of a country. SOEs function to balance the interests of society, including by protecting jobs. It has been a practice to provide subsidies when sources of revenue fall short of covering the costs of SOEs. The State extends various forms of support to SOEs. We can adduce that this is a form of soft budgetary constraint policies. Due to this culture, SOEs were not forced to generate profit to guarantee their long-term sustainability.

Efficient management practices

Efficiency is mostly affected by incentive structure. Regardless of whether a firm is State- or privately-owned, efficiency can be achieved as long as the firm operates in a competitive market, gives full autonomy to the management to make crucial decisions based on market signals and provides performance-based compensation. In reality, the above conditions are rarely met within SOEs.

Sri Lanka is a country which has had a large State sector for decades. Currently, Sri Lanka has about 400 SOEs, according to the Treasury, with over a million employees, which in 2018 made an aggregate loss of Rs. 27 billion. This is nearly one-third of the country’s GDP. These are largely seen as employment providers rather than service providers

Low productivity and inefficiency

The responsibility of SOEs to achieve both commercial and social objectives creates the inefficient use of resources. Moreover, due to the perception that the Government is available to back them up, the employees of SOEs may have a tendency to seek more resources for themselves from the Government. In addition, as they feel that their job security is guaranteed, the employees will not feel pressured to work very hard. As a result, reduced productivity will create a higher burden of cost for the SOEs, which increases the potential for inefficiency.

Lack of autonomy due to policy burdens

Another reason for the less-than-optimal performance of SOEs is that they are entitled to less autonomy as they have to help the Government achieve its special goals. When a firm has more autonomy in labour decisions, profit attainment and output decisions, it will experience higher efficiency compared to SOEs that have less autonomy in making these crucial decisions.

As SOEs are owned by the Government, they were forced to compromise their profit-maximising goal in order to prioritise other Government goals. Hence, they are faced with multiple and conflicting objectives. Moreover, given that these other non-financial objectives make it difficult to measure the performance of a SOE, the incentives of SOE management are not as closely connected to their performance as those of private entities.

New roadmap

In as much as appointees to these State enterprises should be competent and honest people, it is important that politicians should not interfere with their operations. Given the history of State enterprises, achieving efficient administration at State enterprises will be a Herculean task. Unless inefficient management practices are halted, SOEs will not achieve their sustainability in the long run. In order to achieve this goal, professional management should be inculcated at SOEs. With this end in view, the long-felt policy decision has been formulated with regard to appointments to the heads of State agencies under President Rajapaksa.

Challenges ahead

The incumbent appointees will be entrusted with a great responsibility to change the work ethic and culture that have existed all these years. It is in no way a walk in the park for professionals.

Among the other changes they should make are the following:

Appointing the right person is only the beginning of the process. The committee is to decide what candidature screening process is to be followed by the committee in order to achieve the desired results. When it comes to selection through an interview, there is no guarantee that the interview panel always gets the selection right because human behaviour at an interview is judged by outward responses and body language and not by judging how he or she works. Therefore there is a possibility of making a few incorrect decisions in selections.

In order to address this unavoidable error of judgement, a probationary period of three or six months for any position should be introduced before making an absolute final call.

I suggest that a periodical performance appraisal of the appointees be part of the evaluation process. All applicants should prepare a detailed account of how the essential criteria of the position would be satisfied. The new appointees should develop a long-term, preferably five-year plan, and yearly delivery plan for the organisations they will provide leadership to. The plans must be reviewed annually.

(The writer is a Fellow Member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka).