Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 21 January 2020 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Chattalie Jayatilaka

The population of overseas Sri Lankans is nearly three million—that is, one in eight Sri Lankans live abroad.1 This community represents an outflow of human capital that could otherwise have been deployed to further economic growth and development in Sri Lanka.

This significant population of overseas Sri Lankans has the potential to create new opportunities and industries locally. The question which remains is a simple one; how do we bring them back?

Why we need them: Trade diversification

One of the biggest challenges that the Sri Lankan economy is currently facing is the lack of export diversification.2 Return and engagement of overseas Sri Lankans could be beneficial to Sri Lanka in manifold forms: Some possible avenues include encouraging private investments, connecting scientific diaspora to the socioeconomic development as a form of brain gain, and encouraging successful small, and medium level businesses in the host countries to take part in similar ventures in Sri Lanka.3

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), export diversification helps reduce macroeconomic volatility and boosts economic growth in developing countries.4 Sri Lanka can diversify its interests by shifting from solely supporting existing sectors such as tourism or food products to also supporting new sectors such as Information Technology (IT) and electronics.5

The government estimates that the Information Technology-Business Process Management (IT-BPM) sector will create 2.5 more indirect jobs per IT/BPM job due to the innovative nature of the industry and the start-up culture that it cultivates.6 The expertise and experience of overseas Sri Lankans could help accelerate growth in this sector, as well as other linked sectors such as retail, hospitality, and agriculture. The electronics sector too could help digitise the services sector including healthcare, security, and transportation.

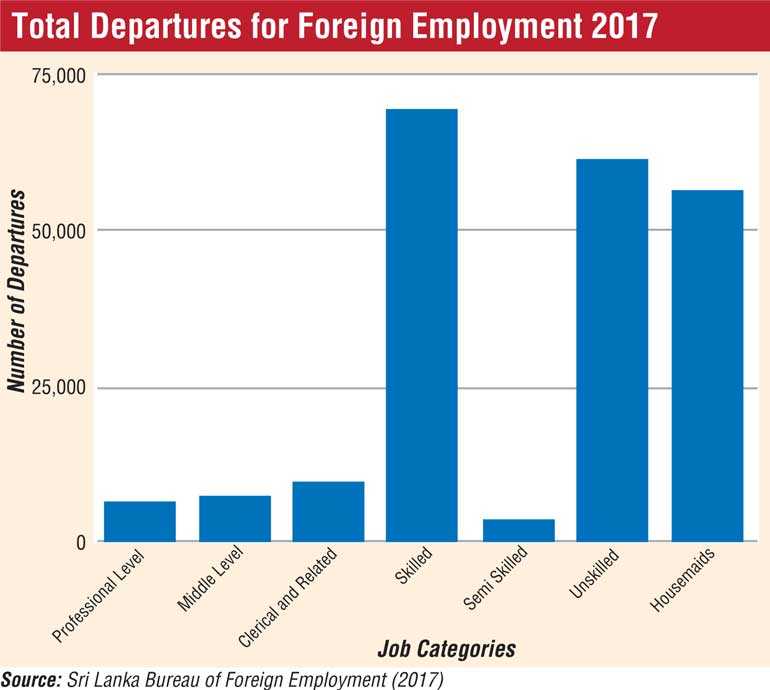

The National Export Strategy lists a lack of skilled workers as a key challenge to advancing the IT/BPM sector, which is estimated to grow to a global $ 2.4 trillion by 2020.7 As seen in Figure 1, Sri Lanka is losing its workers as they leave the country to search for better opportunities.

The benefits of bringing back overseas Sri Lankans are immense. Sanjiva Weerawarana is a prime example of an overseas Sri Lankan who returned to Sri Lanka to create a flourishing business.

Weerawarana completed his PhD in computer science in the US, and spent several years working for IBM before deciding to return to Sri Lanka. He is now the founder and CEO of WSO2, one of Sri Lanka’s biggest software firms which has attracted $ 45 million in venture capital and employs nearly 500 employees at the firm’s global office in Colombo.8

Through specialised knowledge, work experience in international firms, and global connections, returning Sri Lankans could be the catalyst for the revitalisation and diversification of Sri Lanka’s economy.

A look at the visa processes

India and Sri Lanka

There are several significant challenges facing Sri Lankans who wish to return. A key barrier to engagement with overseas Sri Lankans is the bureaucracy involved in entering and working in the country.

Overseas Sri Lankans find it increasingly difficult to obtain the proper paperwork as well as the necessary information required to migrate and start businesses in Sri Lanka. The introduction of dual citizenship has been monumental for overseas Sri Lankans who lost their citizenships when they applied for new citizenship in their country of residence. However, more can be done to simplify the application process as a complicated, lengthy and expensive process may deter applicants from returning home.

India faces a similar issue; the country does not offer dual citizenship to the Indian diaspora which is estimated to be around 17.5 million.9 However, India has been successful in enticing qualified workers to return to India and create flourishing ventures, especially in the tech sector. One policy initiative created by the government was the introduction of the Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) and the Person of Indian Origin Card in 1999. These initiatives granted overseas Indians all the rights of an Indian citizen, except the right to vote or take a seat in government. This allows overseas Indians to return to India to live and work indefinitely, and Sri Lanka may be able to look to India to do the same.10

Overseas Sri Lankans with families who hold foreign citizenship currently face a complicated process when applying for dual citizenship. The lack of a clear process for diaspora families and spouses of Sri Lankan nationals who may wish to return to Sri Lanka to work is a major deterrent.11

China and Taiwan

Similarly, China has eased residency and entry visa requirements for potential returnees who hold foreign citizenship by giving them longer term visas and permanent residence status.

In an effort to ease the process of returning, the Chinese Government together with its Education Commission has established 33 help-centres in 27 provinces to help returnees find jobs, invest in China, and increase technical capacity.12 Countries who are working to draw back its overseas citizens are increasingly initiating policies to ease the way for resettlement and improve the flow of information.

Taiwan is a pioneer in engaging with their overseas population, and the government has been quick to recognise the potential of Taiwanese abroad, not just as a source of investment but also expertise and skills. The Taiwanese government has established multiple platforms and groups for networking and recruitment which provide the information and connections necessary for overseas Taiwanese to resettle with ease.13

China has followed suit with its creation of the annual Meeting of Overseas Chinese Scholars which aims to connect government agencies and domestic companies with overseas experts.14

Sri Lanka currently does not have a branded campaign which aims to connect skilled experts to their respective agencies for potential cooperation links with agencies in Sri Lanka.15 The country could greatly benefit from such efforts as it would facilitate knowledge transfer which is essential for research and development.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka can be more proactive in engaging with overseas Sri Lankans through policies and initiatives that ease the way migrants return, such as simplifying border crossing with flexible immigration policies and increasing the flow of information.

It is a positive sign that the Economic Affairs Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Sri Lanka is now working on the possible avenues of engaging overseas Sri Lankans as development partners. Bridges must be built; we must start to view our overseas kin as valuable for the skills and knowledge they can offer, rather than just financial inflow.

Notes

1Reeves, P. (2014). The Encyclopaedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora: Didier Millet.

2Center for International Development at Harvard University. (2018). Sri Lanka Growth Diagnostic Executive Summary. [Online] Available at: https://srilanka.growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/files/sri-lanka/files/growth_diagnostic_executive_summary.pdf [Accessed 8 November 2019].

3Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2019). Draft Concept Note-Engaging Overseas Sri Lankans as Development Partners.

4Giri, R. Quayyum, S. and Yin, R. (2019). Understanding Export Diversification: Key Drivers and Policy Implications. IMF Working Papers 19(105).

5Malalgoda, C. Samaraweera, P. and Stock, D. (2018). Targeting Sectors for Investment and Export Promotion in Sri Lanka. Export Development Board of Sri Lanka.

6 Government of Sri Lanka. (2018). National Export Strategy. [Online] Available at: http://www.srilankabusiness.com/national-export-strategy/nes-ict-bpm.html [Accessed 8 November 2019].

7Ibid.

8Sennet, J. (2018). Engaging Overseas Sri Lankans to Facilitate Export Diversification. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. [Online] Available at: https://srilanka.growthlab.cid.harvard.edu/files/sri-lanka/files/SriLanka_Export_Diversification.pdf [Accessed 8 November 2019].

9United Nations Population Division. (2019). International Migrant Stock. [Online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimatesgraphs.asp?3g3 [Accessed 8 November 2019].

10Giordano, A. and Terranova, G. (2012). The Indian Policy of Skilled Migration: Brain Return Versus Diaspora Benefits. Journal of Global Policy and Governance. 1(1): 17–28.

11Economy Next. (2019). Sri Lanka Could Benefit from Campaign to Entice Expat Skills: Economist. [Online] Available at: https://economynext.com/sri-lanka-could-benefit-from-campaign-to-entice-expat-skills-economist-11656/ [Accessed 8 November 2019].

12Zweig, D. (2006). Competing for talent: China’s strategies to reverse the brain drain. International Labour Review. 145(1-2): 65–90

13Tzeng, R. (2006). Reverse Brain Drain: Government policy and corporate strategies for global talent searches in Taiwan. Asian Population Studies. 2(3): 239-256.

14Supra, note 12.

15Supra, note 11.

[Chattalie Jayatilaka is a Research Assistant at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). The opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author is affiliated.]