Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 30 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dhanushka Silva

In 1978, the Sri Lankan polity marked a ‘revolution of governance’ (the context jurisprudentially can be referred to as a “paradigm shift” in the system of governance), where no one could precisely ascertain what was to happen or what should happen, but could only resort to predict on what might happen.

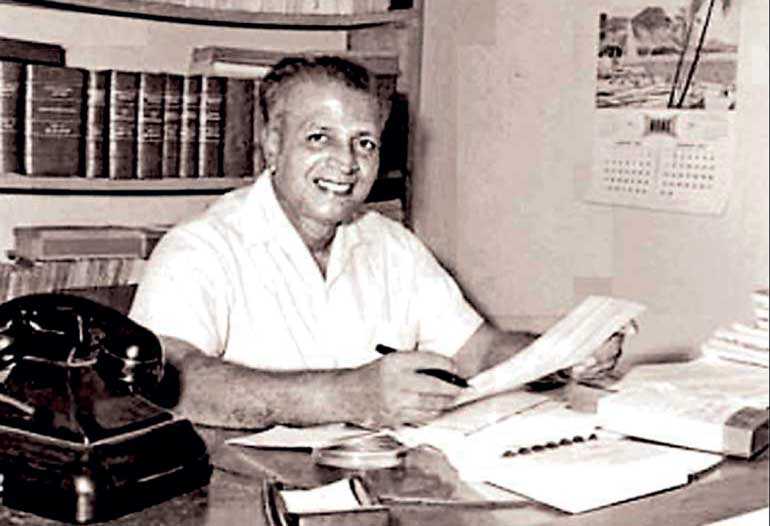

In 1979, two years after, the new Constitution came into being, Dr. Nanayakkarapathirage Martin Perera published a book titled ‘A Critical Analysis of the New Constitution of the Sri Lanka Government’. This is an unusual book written by the legendary leftist intellectual in Sri Lanka politics.

In studying the literature in relation to the Second Republican Constitution, the work has the merit of being the first, competent and rather comprehensive critique which is not entirely based on the author’s subjective political ideologies and judgments, but fundamentally on the objective and multiple disciplines of constitutional law, administrative law and jurisprudence.

It is noteworthy, the author’s purpose, frankly avowed as his enthusiasm, was to outline the ill-effects of our current Supreme Law (the 1978 Constitution) in the future political-constitutional world, although his attention to the new constitutional structure and its failures were not witnessed during his time in the way in which our political generation had to endure it.

Speculation turned into reality

Dr. Perera primarily contended that the new system (constitutional structure introduced under the 1978 Constitution) would smoothly function only with the proper agreement between the President and the Parliament, and inevitably will fail to function in instances where a left majority Parliament has to confront, a right-inclined President or vice versa.

In such anomalous circumstances, the country might face a politico-legal crisis, resulting in the aforesaid disagreement turning into political dilemmas lacking clear solutions. Surprisingly, Dr. Perera’s speculation turned into a reality in 2001-2003. Today in 2018, the situation is more serious given the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. In fact, the recent crisis in Sri Lankan politics is adding on to Dr. N.M’s speculation.

Today, the clash between the President and the Parliament is quite obvious not on mere grounds of politico-ideological differences (left wing verses right wing) between the two institutions as contended by the author, but also on other grounds including the political interests as well. At this point, there is a responsibility placed upon to constitutional critics, political scientists and political actors in terms of theorising the latest political dynamism and clarifying the crisis that has emerged.

Executive Presidency

The major problem of the 1978 Constitution which the author highlighted is its capacity to operate democratically, effectively or responsively through a vast system of office called the Executive President, which he understood to be very closer to a dictatorship. Dr. Perera had the clairvoyance to forecast the possible but negative outcomes that might arise as a consequence of the establishment of an extra-ordinary Executive President based on a loose set of principles under both the United States (US) and French-Gaulist models.

Dr. Perera writes on the Executive Presidency that “it is said that the president of United State is a dictator for four years; in the case of Sri Lanka, this dictatorship extended by two years” (P. 12). Therefore, the author, in the first place, critically assesses the nature of the Executive Presidency in the 5th chapter and notably takes seven separate chapters to extensively discusses how the President controls the whole institutional structure, including the legislature, the cabinet, the referendum, judiciary and proportional representation to retain his dictatorial powers on his hands in the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th chapters.

Fragility of the Parliamentary system

Dr. Perera has eyed the fragility of the Parliamentary system as a constructive implication simply because it neatly reinforces the status of the democracy in a country, when the governments are changed in a shorter period of time. Hence, the constant break-down of the government before the completion of the full official term (except 1965-70 government headed by Dudley Senanayake) became a ‘norm’ in the 1948-72 politics in Sri Lanka.

Against this fragile political backdrop, J.R. Jayewardene (then opposition leader) stressed that it is an urgent need to transform the governance towards an Executive Presidential system for the purpose of ensuring the greater stability (economic and political) of governance. This is why, in 1977, the United National Party in its Manifesto sought a mandate to operate the new Republican Constitution under a strong Executive President.

At this juncture, negating Mr. Jayewardene’s popular claim, Dr. Perera emphasises the Parliamentary system offers fair opportunity, which is largely unpractical under the new system proposed by Jayewardene for an opposition to wield the rein of powers. The author takes government breakdowns in 1960 and in 1964 as examples to validate his argument, where in both cases the election ensued registered a change in the complexion of the existing government by then opposition parties. Further, he writes, “Surely, it is in crucial moments like this that true worth of democracy is manifested” (P.9).

Dr. Perera at this point, understands that the constant breakdown of governance under the parliamentary system, and the political opportunities that emerged for the opposition parties, are paramount in the eye of democracy. The argument, however, is only of theoretical validity, and is not however relatable when looking at the pragmatic politico-constitutional context of Sri Lanka between the years 1948-’72, there was only one out of eight governments which successfully completed the five-year term.

Moreover, the author has not outlined the impacts that could result in case of political instability of the country given such short-term governments. More critically, the author misses how it would affect economic growth and geopolitics. Consequently, the author unintentionally allows the readers to step towards a certain stance in rethinking the best out of the two argumentations in relation to the way in which the politics operated in the ’50s and ’60s.

Instantaneous shift and its effects

Dr. Perera, in the second place, denounces the instantaneous ‘paradigm shift’ of a whole system of governance, the transformation from ‘parliamentarianism’ to ‘extra-ordinary executive presidential tradition’, boosted by the Second Republican Constitution.

Essentially the book reveals the reasons why this change needs to be termed as ‘sudden or instantaneous’: firstly, because the Second Amendment to the 1972 Constitution being treated as an urgent matter; secondly, because the Second Amendment is none other than a hasty effort to transform the institutional structure of the Constitution; thirdly due to the lack of any inclusive discussion on how the new Constitution ought to be acceptable to a wider society.

As has been correctly acknowledged, the sudden changes in the polity undoubtedly led to the perpetuation of instability, insecurity and disloyalty amongst the people. More seriously the law of the Constitution may fail to respond to the needs of the people in the island nation.

As Dr. Perera notes, for the law to be credible it must evolve over a period of time and must be capable of changing with the advancing social evolution of the people. The author notes down in the preface of his work as follows: “every parliament has seen a change of government and the people have displayed a commendable degree of political maturity” (P.8).

It is clear that this idea interlinks to the Volksgeist thesis put forward by a Frankfurt jurist named Savigny, where he argues the law or the legal system is the product of general conscience of the people and the manifestation of their sprit.

But Dr. Perera’s argument makes complexities here, and confuses ordinary reader’s minds, as he takes a legal tradition called Anglo-Saxons which has not derived from Sinhalese consciousness, and has not changed with the political maturity of the Sinhalese to validate his argument. In this light, the author’s understanding, the way in which Anglo Saxon parliamentary system that merely evolved with the interest of the political elitism in Sri Lanka, implicates serious limitations in terms of Savignian thesis.

Value and durability

In a nutshell, the validity of Dr. Perera’s critique of the 1978 Constitution spreads across a remarkably wide period of time even if it encompasses theoretical ambiguities and discrepancies as noted above. Nevertheless, the value and durability of the work is recalled time and time again by certain political and constitutional challenges coming under the present Constitution. Therefore, the book will remain on the preferred list of those who are seeking insights into the functionality, durability and liveability of the Second Republican Constitution of Sri Lanka.

The book further ascertains the stance of those who are sincerely worried about the danger of an over-grown and an over-powerful institutional matrix, especially the Executive Presidential system established under the 1978 Constitution.

(The writer can be reached via email at [email protected])