Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 23 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Bilesha Weeraratne

Labour migration from Sri Lanka has experienced many changes in recent years. Often, these are due to traditional reasons, such as oil price fluctuations and the slowing down of growth in destination economies.

Another factor that could contribute to shifts in migration patterns is the transformations taking place in the world of work in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). This blog examines the influence of 4IR on changing patterns of labour migration from Sri Lanka.

4IR and workers

4IR is the age of intelligence that brings together technologies such as artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotisation, and automation. In harnessing these technologies, the traditional models of employment are increasingly replaced by new models.

For instance, employment platforms are making work piecemeal, where workers are hired for ‘gigs’ instead of employment with an employer, and a disconnected team of workers work in isolation via a platform on a single project, without reflecting any traditional characteristics of a ‘team’. At the same time, the new world of work is increasingly polarised across low skilled – low paying jobs and high skilled – high paying jobs.

Status quo in Sri Lanka

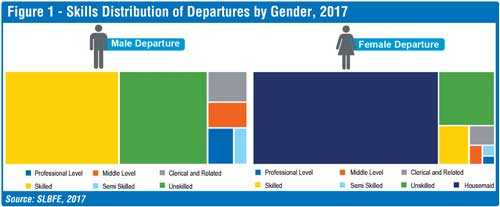

In 2018, Sri Lanka sent a total of 211,459 workers for foreign employment, while the total number of departures and the significance of female migrant workers have continued to decline. More than 90% of female migrant workers from Sri Lanka are low skilled. On the contrary, among male departures from Sri Lanka, unskilled workers account for only about 37%, while the bulk is skilled workers (47%), who are less likely to be displaced in the 4IR (Figure 1).

Overall, despite numerous efforts over the years, Sri Lanka has had limited success in sending more high skilled migrants, and the share of ‘skilled’, ‘middle level’, and ‘professional’ categories among worker departures is still relatively small. This shows that Sri Lankan migrant workers continue to possess more traditional skills, and are likely to face obstacles in the 4IR era.

4IR in the Middle East

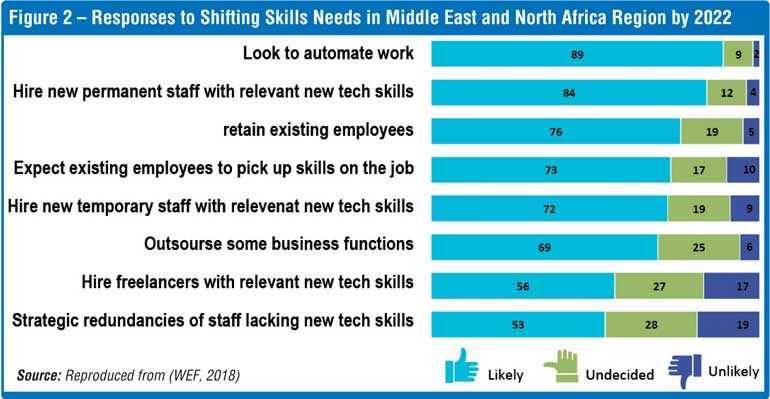

As indicated by studies, the work environments and employment structures in the Middle East, Sri Lanka’s main destination for migrant workers, are transitioning quickly. The projected trends show that 90% of employers in the region are likely to replace workers by automation, 70% are likely to look for employees with 4IR skills, and 73% expect existing employees to pick up 4IR skills (Figure 2). Such adaptation strategies by employers in the Middle East may have contributed to the decline in demand for workers from Sri Lanka.

At the same time, nearly 70% of employers in this region are expecting to outsource work and over 50% would hire freelance workers with relevant skills. Such changes in the employment structure would have also contributed to the declining trend in total departures from Sri Lanka.

Where is the future?

Despite challenges, in this new era of 4IR, Sri Lanka appears to have immense untapped potential for labour migration in two priority areas.

1. ‘Human-only’ niche

In spite of the growing appetite for automation, migrant workers from Sri Lanka could still carve a niche in jobs that involve ‘human-only’ tasks. Here, the significance of female domestic workers in the composition of migrant workers from Sri Lanka should be noted.

Despite being routine and low skilled, tasks of female domestic workers, such as caregiving and household duties, cannot be easily robotised or automated. As such, whilst acknowledging the possible negative implications on the families left behind, Sri Lanka should understand the hidden value and potential of low skilled female migrant workers in terms of ‘human-only’ jobs.

To this effect, Sri Lanka needs to urgently revisit restrictions, such as the Family Background Report (FBR), to facilitate foreign employment in this niche market segment. Nevertheless, given the best-case scenario of repealing FBR appears too far-fetched in the political setting in Sri Lanka, the country needs to focus on developing a mechanism to protect and ensure the wellbeing of the family left behind. On the other hand, Sri Lanka ought to team up with other labour-sending countries and work towards marketing this ‘human-only’ niche to leverage higher wages and to improve worker welfare and protection in destination countries.

2. ‘Digital-collar’ workers

In addition to the continued demand for low skilled, blue-collar workers, the 4IR is also creating demand for a new breed of workers identified as the ‘new-collar’ or ‘digital-collar’ workers, who are required to capture, analyse, and store the large amounts of data created by modern manufacturing processes embedded with sensor technologies, the IoT, automation, and robotics.

Digital collar workers would have higher-tech skills or specialised training compared to the traditional blue-collar workers, and they would acquire skills through non-conventional education. In this era of 4IR, Sri Lanka should focus on digital-collar workers as the other most important group of migrant workers, due to the relative ease in repurposing blue-collar into digital-collar workers.

4IR has influenced labour migration across the globe as well as in Sri Lanka. From a global scale, Sri Lanka’s uptake of 4IR technologies is still at a rudimentary stage, where the Digital Road Map for the country was only launched as recently as June 2019. Nevertheless, some of the changes in recent trends in labour migration from Sri Lanka can be attributed to the 4IR, and Sri Lanka can remain competitive in this era as a labour-sending country if policies hone in on ‘human-only’ and digital-collar workers

Specifically, Sri Lanka already has a framework for Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL), which aligns with the assessment of skills of digital-collar workers. The RPL evaluates competencies acquired through informal and non-institutional learning and provides an internationally-accepted qualification within the framework of the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ).

In this context, in future, Sri Lanka ought to encourage workers with skills acquired by informal means to get the same validation via the RPL framework. At the same time, Sri Lanka should actively harness skills transfer related to ‘on the job training’ acquired abroad, by engaging returning migrant workers or those coming on holiday/vacation, to prepare potential migrant workers to cater to the growing demand for digital-collar workers abroad.

Finally, the 4IR has influenced labour migration across the globe as well as in Sri Lanka. From a global scale, Sri Lanka’s uptake of 4IR technologies is still at a rudimentary stage, where the Digital Road Map for the country was only launched as recently as June 2019.

Nevertheless, some of the changes in recent trends in labour migration from Sri Lanka can be attributed to the 4IR, and Sri Lanka can remain competitive in this era as a labour-sending country if policies hone in on ‘human-only’ and digital-collar workers.

(This blog is based on a chapter written for the forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2019’ report on Transforming Sri Lanka’s Economic Landscape in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)