Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 29 January 2020 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Suren Sumithraarachchi

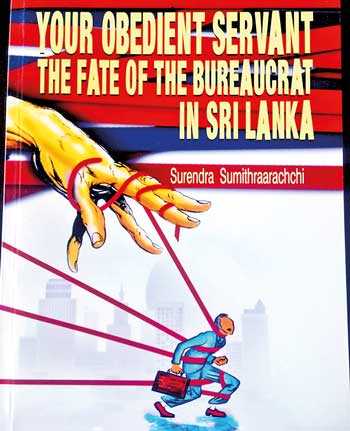

Sarasavi Publishers 2019 Reviewed by H.L. Seneviratne

This book deals with the higher bureaucracy in Sri Lanka, and its focus is bureaucratic behaviour. It is about local bureaucrats, not those of British origin who historically inhabited the bureaucratic terrain with decreasing density as colonial rule waned. It considers loyalty to a set of rules, rather than to a person, the marker of ideal bureaucratic behaviour, one that the vocabulary of sociology calls “rational-legal”.

The change from loyalty to a person to loyalty to a set of rules and regulations started with the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1832, and was strengthened by the Donoughmore administration of 1931. It was both a political and moral progression that one would expect to progress further for the greater benefit of the society. However, rather than a further progression, what has come about is a reversal. Bureaucrats have been changing from allegiance to rules, to allegiance to a person, the politician.

The central concern of the book is to explain how and why this has come about. In this task the author uses the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concepts of Habitus, Symbolic Capital and Field. Habitus is a lasting disposition formed in a person through primary socialisation with members of the family (Primary Habitus), and dispositions formed through exposures during school, university and other life experiences (Secondary Habitus).

Symbolic Capital refers to the state of recognition and respect formed through an admixture of economic, cultural and social capital. The book tries to explain the perspectives and behaviour of the different categories of bureaucrats by situating them in their primary and secondary socialisation, and their social, cultural and economic capital.

The Donoughmore civil servants were the earliest to manifest rational-legal behaviour, and the author cites the interactions between these elite bureaucrats and the peoples’s representatives in the legislature of the time, the State Council. The same group of elite bureaucrats continued under the Soulbury administration. The two groups, the politicians and the bureaucrats, had been schooled together, and shared a common culture. They shared the same Habitus and the same Symbolic Capital, making the power gap between them and the politicians minimal or non-existent.

This tranquil scene was to get rudely disturbed by the religio-nationalism that had been brewing underneath, and that surfaced decisively in its electoral victory in 1956. This election was to enthrone a different kind of politician, whose Habitus and Symbolic capital were different from those of the bureaucrats who continued to come from the pre-1956 elite. These politicians held the traditional ideology of requiring personal loyalty to them, while the bureaucrats continued to hold the view that their loyalty was to a body of impersonal rules. In this contest, while the bureaucrats gained some victories, those were few and far between, and they were fated to loose.

The list of legislative acts that followed reads like an obituary of rational-legal bureaucracy. The first of these was the 1963 “restructuring” of the bureaucracy when the Ceylon Civil Service was abolished, and a broader based Sri Lanka Administraive Service (SLAS) was established. Next, in 1972, the Public Service Commission was abolished, and the bureaucracy was placed under the Cabinet, thus instituting direct political control over the bureaucrats. The 1978 constitution vested the president with wide powers over the bureaucracy, effectively controlling all senior appointments, transfers and promotions. (The 19th amendment which restored some degree of independence to the bureaucracy is outside the scope of this study. In any case, under the prospective new government, the 19th amendment faces an uncertain future).

The changes in the social composition of the bureaucracy complemented the legislatively initiated corrosion of rational-legality in the bureaucracy. Increasingly, the new recruits came from middle-class, non-elite families with lower status, power, and social acceptance than the previously dominant elite bureaucrats. They were educated in rural schools and exclusively in local universities. They were recruited through the Sri Lanka Administrative Service (SLAS)’s open competitive examination; were absorbed into the higher bureaucracy from non-Civil Service staff grades; or promoted from clerical grades. Although they enjoyed the status, power and social acceptance of their SLAS positions, they were less confident and self-reliant than the Civil Service bureaucrats they replaced.

|

| Prof. H.L. Seneviratne |

The book identifies three modes the bureaucrats adopt when dealing with politicians: (a) acting within a rational-legal framework, (b) appeasement, and (c) subservience. The mode adopted since the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms (1832) up to 1956 was rational action within a legal framework. With restructuring in 1963 and vesting of the bureaucracy in the Cabinet in 1972, appeasement replaced rational-legal action. Under presidential rule introduced in 1978, subservience replaced appeasement.

Subservience is the willingness to obey others unquestioningly. It is found in relationships where the power gap is wide, and where the subordinate suffers from insecurity and low self esteem, due to either his/her inadequacies or intimidation by the superior partner, in this case the politician. Subservience in the Sri Lankan bureaucracy was initially seen in breaucrats absorbed from lower rungs, after the 1963 restructuring. At that time their numbers were very small, but subservience became more common after the 1972 aboliton of the Public Service Commission, and was further reinforced by the 1978 constitution.

The abolition of the Public Service Commission in particular removed the independence of the bureaucrats to make rational-legal decisions, and made them dependent on politicians for their survival. The need for survival brought down the self esteem of bureaucrats, thus widening the gap between them and the political leaders, and leading them to subservience. Most of them had weak inherited Symbolic Capital and were relying on their acquired Symbolic Capital, accrued essentially through their position in the bureaucracy. This resulted in their forming subservient behaviour to avoid conflict with their political masters. The five-sixth majority the 1978 regime enjoyed encouraged the political leadership to cultivate a superior mind set, and demand obedience and personal loyalty from the bureaucracy. Often these were demands that violated the regulatory framework, and impossible for the bureaucrcats to fullfil legitimately. But it was only by meekly fulfilling these demands that the bureaucrats could save their positions.

Subservience was further reinforced by the 18th amendment’s removal of all constraints on the president’s power to make appointments to key bureaucratic positions. This increased the already wide gap between the president and the bureaucracy as the promotional prospects of the bureaucrat depended solely on the whim of the president. The five-member parliamentary council to advice the president on appointments was not capable of opposing the president’s choice, as their mandate was non-binding. The president used the provision to nurture and sustain the existing patronage-based system. This set an example for the political leaders across the provinces who insisted that only those bureaucrats they recommended got appointments, transfers and promotions. This widened the power gap between political leaders and the bureaucrats in the provinces as well, and they were forced to conform to the dictates of the politicians as their only means of appointments, promotions and transfers.

The decline of the bureaucracy in Sri Lanka is not news to even the most cursory observer, but that does not detract from the value of this painstaking account of the process of that decline. If it is a well-known story, it is still a story well worth repetition, both for its own sake, and as one more indicator of the general malaise that has been afflicting our society ever since hegemonic religio-nationalism eclipsed the clearly discernible path to a patriotic Sri Lankan national identity, and a happy, prosperous, urbane and modern nation.

Besides, the perspectives on the bureaucracy based on interviews with the handful of distinguished men and women of the former Ceylon Civil Service, and with senior administrators still in service, constitute original and valuable material. While the book is not intended as anything other than an objective and scholarly study, it is implicitly yet inescapably a critique of our sordid political culture.