Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 27 May 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Manoj Thibbotuwawa

COVID-19 is dealing an unprecedented blow to economies around the globe and the health risk is only the tip of the iceberg. Among the many impending crises resulting from the pandemic, rising food insecurity due to lockdown measures is one of the most critical. The 2020 Global Report on Food Crises highlights that the pandemic is likely to limit access to dietary energy and diversity, safe water, sanitation, and healthcare and will create high levels of malnutrition.

COVID-19 is dealing an unprecedented blow to economies around the globe and the health risk is only the tip of the iceberg. Among the many impending crises resulting from the pandemic, rising food insecurity due to lockdown measures is one of the most critical. The 2020 Global Report on Food Crises highlights that the pandemic is likely to limit access to dietary energy and diversity, safe water, sanitation, and healthcare and will create high levels of malnutrition.

Sri Lanka is no exception. While the country has been battered by major natural disasters and long-lasting civil conflicts, it has not experienced a pandemic of this scale and severity. The food system in Sri Lanka has already proven to be vulnerable and inefficient in coping with such crises. Further, malnutrition is a persistent problem in Sri Lanka, with severe regional disparities. Policymakers are thus faced with the dual challenge of mitigating the short and medium term impacts of COVID-19 as well as strengthening Sri Lanka’s food systems in the long term. This blog examines how COVID-19 could worsen food security issues in the country and what measures can be taken to overcome these challenges.

Sri Lanka’s food system is highly vulnerable to COVID-19

Sri Lanka’s food system comprises food produced locally (78%) and imported (22%). The domestic production of major food items like rice, meat, eggs, fish, vegetables, and fruits exceed 88% of the total supply. Yet, many essential food such as wheat and canned fish (100%), pulses (87%), sugar (85%), vegetable oil (79%), onions and potatoes (70%), and milk products (53%) are imported. As such, the proper functioning of the food supply chains and the food flow are key elements of food and nutrition security.

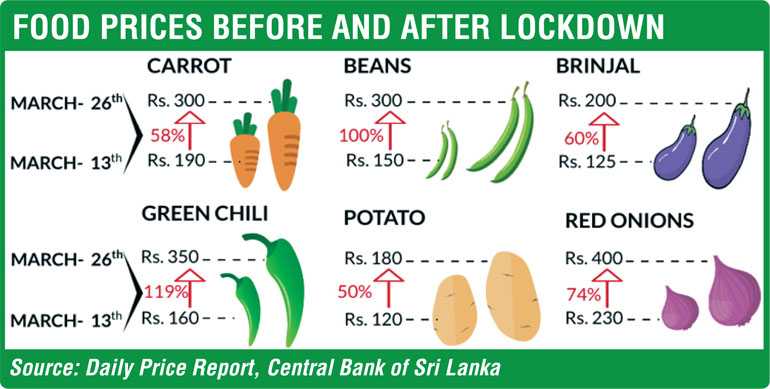

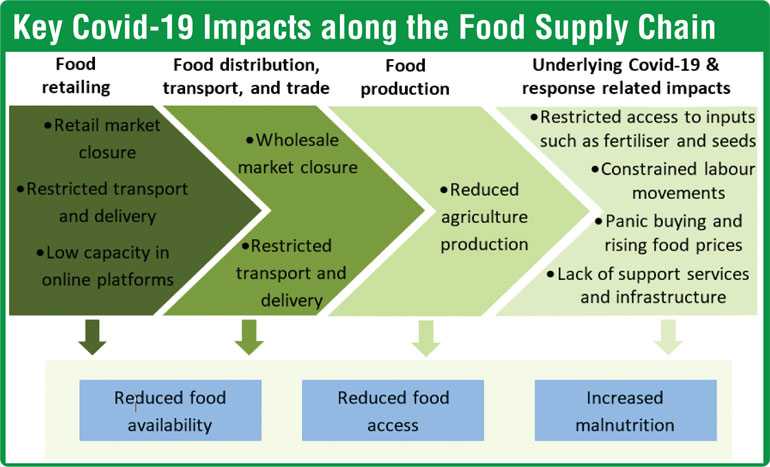

The prolonged curfew imposed in Sri Lanka in mid-March, to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, highlights the vulnerability of Sri Lanka’s food system. Consumers were not able to buy food as distribution channels collapsed due to the restrictions on transport and storage and the closure of major wholesale and retail markets. Food shortages were exacerbated due to panic buying and rising food prices of both domestically produced and imported food items. These issues make life harder for the urban poor, amidst massive unemployment, especially among daily wage earners.

Digital market alternatives, such as online platforms and mobile applications – despite their potential to connect people during lockdown – failed to deliver, primarily due to lack of capacity and unfair prices. As a result, initial hopes of online ordering and home delivery being a solution to the crisis faded even amongst sophisticated, middle-class populations.

Increasing concerns over access to food and food affordability resulted in public dissent against lockdown measures in densely populated, urban areas, especially in places where high numbers of daily wage earners live. Anecdotal evidence suggests that poor households had to depend on friends and family, use savings, or get into debt, just to buy food.

Beyond disruptions to food supplies

While Sri Lanka has not experienced countrywide food shortages, the crisis created by the breakdowns in supply chains is now resulting in farmers losing income and low farm gate prices. Traditionally, agricultural markets in Sri Lanka are not readily available to absorb the produce at the time of harvesting, and it has been left to organised traders to purchase crops at relatively low prices. The widened wholesale-retail price spread too did not benefit the farmers who are usually price takers. Moreover, restricted access to agricultural inputs, such as fertiliser and seeds, constrained labour movements, and the lack of support services and infrastructure have already started affecting food production in Sri Lanka. Also, inefficiencies in food supply chains could lead to food losses and waste.

All these factors, along with reduced demand from domestic and foreign customers and market uncertainties, might push farmers to the brink of poverty. As a result, future shortcomings in food production and reduced food availability are to be expected. Overall, these trends indicate that the shock caused by the pandemic is not just short term, but will have far reaching consequences, especially on vulnerable and marginalised

populations.

Government’s struggles

On top of a growing health hazard, Sri Lanka’s government has also been overburdened with ensuring the food security of households. It launched several initiatives to help food producers, distributors, and consumers during the lockdown.

Agriculture activities were exempted from curfew restrictions and farmers were allowed to continue with their operations. Also, the government introduced maximum prices for vegetables, to provide relief to consumers, while safeguarding farmers.

Meanwhile, it introduced a new procedure for the distribution of fruits and vegetables at Divisional Secretariat level, by the Economic Centres. Restrictions were imposed on the importation of locally grown crops, including rice and sugar, to strengthen domestic agriculture. Importantly, the ‘Saubhagya’ National Programme on Harvesting and Cultivation was launched, to develop one million home gardens islandwide. Finally, a consumption support of Rs. 5,000 was given to about four million vulnerable Sri Lankans, including senior citizens, people with disabilities, kidney patients, and Samurdhi recipients.

However, these efforts are insufficient. The government stepping in to control prices and purchase harvest has provided some relief for consumers and farmers. However, there have been issues at the lower end of the supply chain, with most vulnerable farmers not being able to sell their produce even at unprofitable prices, partly due to the exploitation by middlemen involved in the government’s purchasing program. Also, while the home gardening program looks promising, its real economic impact will largely depend on whether the interest shown by people will remain post COVID-19, and its long term impact on commercial cultivations. The consumption support programme is poorly targeted, with many vulnerable people not receiving adequate support due to the lack of reliable information required to administer cash transfers.

Way forward

The complexity of the unfolding crisis demands well thought out policy responses, based on robust evidence. Even if the spread of COVID-19 begins to ease off shortly, the government cannot pass it off as a temporary shock. Besides the turmoil it has already created, COVID-19 has shaken the country’s food system to its core, revealing its high vulnerability to external shocks. Hence, it is important to strengthen the food system to face future blows.

Therefore, Sri Lanka needs a well-established and permanent mechanism of public food distribution at the central level, with clear linkages to provincial and local government institutions. Further, a regular monitoring system should be established to safeguard the local food distribution system from possible malpractices and to ensure the effectiveness of government interventions. Also, a digital food and nutrition surveillance system, with more frequent data collection, should be set up to monitor vulnerable populations, to improve targeting in crisis situations. Finally, the increased demand for digital marketing platforms should be capitalised at both ends of the food supply chain.

(This blog is based on a chapter written for the forthcoming ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’ report on ‘Globalisation and Disruptions: Reviving Sri Lanka’s Economy COVID-19 and beyond’. Manoj Thibbotuwawa is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.)