Monday Mar 02, 2026

Monday Mar 02, 2026

Friday, 28 August 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

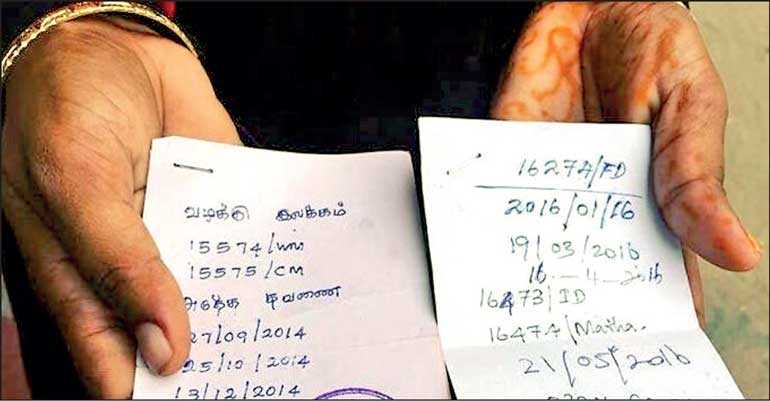

Following the tragic Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019 and increased attention on the Muslim communities, MMDA reform was cast into the spotlight – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Muslim Personal Law Reform Action Group (MPLRAG)

A year ago, on 22 August 2019, the then Cabinet approved a set of reform recommendations to the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA), tabled by the then Ministry of Muslim Affairs in coordination with Muslim Members of Parliament. However, a year later there has been no progress on reforms. It has been another year during which Muslim women have endured the discrimination and injustice and sometimes violence perpetuated under the MMDA.

The problems and challenges with Sri Lanka’s MMDA and Quazi court system is well known and well documented. It is undeniable that Muslim women are the most affected by discriminatory provisions and procedures and unjust practices under the MMDA, and the Quazi court system, since its enactment in 1951. The MMDA has in effect rendered Muslim women and children second class citizens.

Recap of events leading up to Cabinet approving proposed amendments

Following the tragic Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019 and increased attention on the Muslim communities, MMDA reform was cast into the spotlight. Muslim MPs scrambled to support many reforms including reform of the MMDA. In July 2019, the MPs came up with a set of recommendations which included some progressive positions.

Conservative elements immediately prevailed on the Muslim MPs. MPLRAG and other Muslim women’s groups maintained their position that reform must be designed to serve its purpose. MPs organized meetings with conservative groups and some progressive religious scholars to barter on recommendations. Disappointingly, the final document forwarded to the Ministry of Justice by the then Ministry of Muslim Affairs on 6 August 2019 did not address key equality issues for Muslim women such as minimum age of marriage and female quazis. Women’s groups reiterated that token reform did not serve Muslim women and children nor did it serve Muslim communities at large.

The Cabinet Paper on MMDA reform failed Muslim women and children

The Cabinet approved recommendations falls significantly short of amendments advocated for by women’s groups as well as the Chairperson’s recommendations in the official report of the 2009 Committee appointed to advise on reform (JSM report).

The proposed amendments among other things, provided exceptions to the minimum age of marriage, did not provide for equal divorce rights, did not abolish polygamy, did not recommend allowing women to be Quazis nor specify the nature and extent to which the standards within the Quazi courts should be improved.

Current challenges to reform of the MMDA

The past few years has seen the pressures and threats from conservative community groups with the All Ceylon Jamaiyyatul Ulama (ACJU) being particularly vocal and active against reform. These measures essentially displaced principles of equality and justice and basic fundamental rights of Muslim women.

Last year, we also saw nationalistic anti-Muslim voices calling for the abolishment of the MMDA. This call which promoted a policy of ‘one law, one country’ appeared to use Muslim women’s concerns to justify broad-based disentitlement of minorities and curtailment of expressions of religious and cultural rights of minority communities. It failed to appreciate that the concept of ‘one law’ within a majoritarian context must strive to positively recognise minority rights and concerns. It was another voice that displaced Muslim women’s experiences.

The silence of MPs in playing their role of representing vulnerable and disentitled citizens of Sri Lanka, in this instance being Muslim women and children, has been constant. Political will to address longstanding grievances that continue to affect the lives of Muslim women and children each day has been missing throughout.

In light of these multiple challenges, piecemeal or tokenistic reform of the MMDA is a tempting option for lawmakers. However, we reiterate again that piecemeal reform fails to achieve the purpose of reform and Muslim women and children, and communities at large will continue to suffer at the hands of a repressive system.

What reforms are needed

The main objective of MMDA reform is improving the lives of Muslim women and children and by so doing improving the lives of families in Muslim communities in Sri Lanka. The MMDA must be reformed comprehensively. There is no other way to ensure justice for Muslim women of Sri Lanka. Therefore, the recommendations suggested by the 2009 MMDA Reforms Committee, must be taken as a starting point and improved upon to ensure all gaps are meaningfully addressed.

The reform priorities are as follows:

Child marriage – Minimum age of marriage for all Muslims must be 18 years without any exceptions.

Women Quazis – Women should be eligible to be appointed as Quazis, Members of the Board of Quazis, Marriage Registrars and assessors (jurors).

Uniformity – The MMDA must apply uniformly to all Muslims without causing disadvantage to persons based on sect or madhab (schools of jurisprudence).

Bride’s consent and autonomy – Signature or thumbprint of bride and groom is mandatory in all official marriage documentation. Adult Muslim women are entitled to equal autonomy and need not require the ‘permission’ by law of any male relative or Quazi to enter into a marriage.

Registration – Mandatory registration required for legal validity of marriage.

Marriage contracts – Introduce, recognise, and facilitate the concept of the marriage contract to be entered into by Muslim couples prior to marriage, where they can opt for monogamy among other mutually agreed conditions.

Dowry – Abolish dowry/kaikuli – or, at a minimum, it must be mandatory to record the details of movable and immovable property given in trust and it must be recoverable on dissolution of the marriage.

Polygamy – Abolish polygamy – or, at a minimum, make polygamy permissible only under exceptional circumstances, and under specific conditions including: financial capacity, consent of all parties involved, and under the supervision of court that fairness is achieved.

Divorce – Provisions of divorce must apply equally to women and men. Conditions to be imposed for obtaining Talaq and Fasah divorce. Procedures for divorce initiated by husband and wife must be the same, including appeal process. Types of divorce (including mutual consent divorce), grounds for divorce and an effective and efficient process of divorce should be applicable to all who are governed by MMDA.

Maintenance and compensation – The MMDA must provide specific guidelines for

assessment/calculation of maintenance payments for women and children. The MMDA must make mandatory provision for payment of mata’a (compensation) by the husband to the wife in cases where fault of the husband has been established.

Quazi Courts – Improve the quality of the Quazi court system and qualification of Quazis, to ensure competent, efficient access to justice for women and men, as well as a robust monitoring mechanism.

Monitoring Quazi Courts – Establish a system for robust and regular monitoring of Quazi court proceedings and records.

Option to opt out – Grant Muslim couples the option to marry under the General Marriage Registration Ordinance (GMRO) if they so wish.