Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 26 February 2020 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

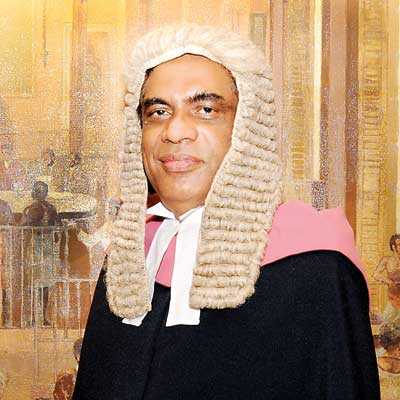

Following is the address by Court of Appeal President Justice A.H.M.D. Nawaz on the occasion of the ceremonial welcome accorded to him by the Bar on 20 February

Mr. Sanjay Rajaratnam P.C, Honourable Acting Solicitor General, Mr. Kalinga Indatissa, P.C, Honourable President of the Bar Association, Honourable President’s Counsel, Honourable Members of the Bar, my dear friends, ladies and gentlemen, i quite appreciate the words of welcome expressed on behalf of the Bar and those laudatory comments of two distinguished alumni of my alma mater have struck an evocative chord in the recesses of my heart. I thank the two President’s Counsel for their kindly words.

|

| Court of Appeal President Justice A.H.M.D. Nawaz |

The attendance of the honourable members of the Bar, the enthusiasm of my friends with which they greeted the news of my appointment and the eloquent warmth of messages have moved me deeply. The loyalty of my colleagues on the bench and other members of the Judiciary who have expressed their solidarity by coming to this welcome strikes a deep emotional chord…I feel overwhelmed.

The Attorney General’s Department and the Bar meant a great deal to me. Cumulatively I was a member of both the official and unofficial Bar for more than two decades. For me the practice at the bar was more than a professional pursuit. It had been in effect my life in a profoundly relevant sense: consuming almost my entire intellectual and moral energies for more than two decades; influencing and provoking my responses to a panoply of causes and institutional exigencies that impacted upon me during some significant periods of legal history in the life of my country; sustaining for me some of the deepest emotional relationships which it generated; regulating much of my moral compass: conditioning my intellectual discipline and in the last instance giving focus and substance to much of my identity as a counsel and judge as I moved from the first exciting flashes of adulthood through the maturing apprehension of approaching middle age. In the distant future I will no doubt savour the fruits of a possible winter of my life.

There is nostalgia and satisfaction – even fearless pride – in the recall of the travails and tribulations that have led to the richness and fulfilment judicial life has offered me and it is an inescapable verity that my journey to the pinnacle of the Court of Appeal has been long and arduous and has taken me an unusual five long years but my dabbling in all its varied jurisdictions has been long enough to impress upon and invest me with the independence and learning which should characterise the administration of this great court and the robust and vigorous adjudication of any issue at hand.

The Court of Appeal website and law reports afford an enduring record of my judgments aggregating close upon 300 in number and the tireless industry in work. They range from all provinces of the law. In the discharge of my judicial functions day-in-day out the study and practice of law have always appealed to my idealism, because the justification for law is its pursuit of justice and its capacity to resist injustice.

But I have observed a wide gulf between law and justice. It is often the case that it is through the instrumentality of law itself and the institutions of justice that palpable injustice is inflicted on people and the vulnerable but voiceless majority. But this paradox is not without compensation; it has enabled me to focus more intensely and consciously on what the philosophical and ethically legitimate ends of justice should be, the degree to which they are manifestly inconsistent with the laws which regulate life in the land of our birth, the reason why they should be reversed and never, never be repeated.

So I articulate the proposition that law and justice cannot be distant neighbours. If they become distant neighbours in the hands of judges, the quality of justice is undermined and it reminds me of Jesus Christ who said, “The Sabbath was made for man and no man for Sabbath.” Justice must not be rigid and the rigour of the law un-tempered by milk of human kindness is not justice but akin to denial of it.

As that great American judge Frankfurter said: “protected in their sanctum justices may engage in that process of discovery that will yield the right answer – not an objective, eternally fixed answer, but the right answer for the time – which they will explain through “reasoned elaboration”. This reminds us of Lord Denning’s truism across the Atlantic – “a judgment must mature by deliberation and not by precipitation”. Speedy justice cannot be the substitute for a well-reasoned judgment.

This is the focus shared by so many of the bar. There are striking examples of the courage and tenacity displayed by advocates of extraordinary gifts and talent, but there is also a demeaning state of impotence which debilitates the mainstream.

Instead of a coalescence between law and justice, there has grown a dangerous distance between the two, and the law and lawyers have begun to lose much of their legitimacy among people whom they are unable to protect against injustice.

All this is painfully true, but it is not the whole truth. I have watched with wonderment that there are other influences and traditions at the bar which never died and which must be crucial for the commitment we have made under the Constitution to bring real justice, dignity and freedom to all the citizens of this extremely exciting country, of so much promise and richness: so much romance and cruelty. I am infinitely richer for the opportunity to be exposed to these influences and traditions.

The first is the tradition of thorough scholarship, pursuit of forensic excellence, capacity for rational thought, intense intellectual energy and unremitting discipline which attorneys have always been expected to apply in the discharge of their briefs. There must be few endeavours, in all civilisation, which can compare with the totality of commitment and the punctilious regard for detail which a competent and conscientious advocate harnesses in support of his or her case. This is a great and impressive tradition bred in very competitive conditions, which enriches the level of legal debate in the resolution of jurisprudential and actual disputes, and ultimately in a very crucial sense, the quality and legitimacy of the Bench and the image of justice itself.

A second and related tradition is a fierce independence and an uncompromising standard of intellectual integrity and capacity for objectivity which informs the best of the Bar. It is sometimes displayed with a towering magnificence and with it comes a depth of courage and a willingness to champion causes and litigants, often unpopular in the public perception.

As both a counsel and a judge, I often watched with absolute awe the depth of these traditions and their potential to bring sparkle in forensic combat in the Bar; to bring admiration – even adulation – from the public and in their even more crucial potential, ultimately to bring legitimacy and respect for law itself, and to grace our civilisation which law strives to serve.

It is my resolve that the Bar must regain its pristine glory and I will take every step possible to encourage and preserve these traditions. Whilst these great traditions are cherished and fostered by those last of the Mohicans who are delightfully with us and a cohort of some of the finest of President’s Counsel and attorneys, there are afflictions that affect the profession in such a way as to permit a degeneration of these traditions. We as equal partners are duty bound to rise to the occasion and stem the potential degradation of these traditions.

While such articulations for great traditions remain pertinent and valid even in this age of technology, there is an imperative need to be guided by the great religions of our country that sustain us. As the Dhammapada goes on to observe, a guardian of the law must abide by the law and act both lawfully and impartially – Dhammapada 19.2. The concept of right thought is expounded in detail in Buddhist writings which contain much wisdom relevant to the work of the Judiciary. Buddhist teaching reminds us that taking joy in one’s work would make concentration easier. In the words of the Buddha ‘from gladness comes joy, with joy the body becomes tranquil, and the mind that is happy becomes concentrated – Dhammapada 1.74.

In Hinduism, the Laws of Manu comprise several hundreds of sections and section 118 specifies that evidence and judicial proceedings should be free from covetousness, distractions, error, friendship, wrath and ignorance. Hindu law is quite particular that the judges should be equipped for their task both through the requisite knowledge of law and the requisite standard of conduct.

Chapter 23 of the Gospel according to Matthew sets out a number of observations of Jesus on those who teach and administer the law. It should indeed be required reading for all lawyers and judges.

In the first place, Jesus Christ gives an overall perspective to the legal profession when he stresses that knowledge and expertise in the law is not a means of advancing oneself, but a means of brotherly service and help to those in society who need assistance.

The Holy Quran in Sura 4 verse 135 makes it quite clear all justice is divine scrutiny and any failure will not pass unnoticed – “If you distort justice or decline to do justice, verily Allah is well acquainted with all that you do.”

So the foundational pillars of democracy and judicial conduct occupy an exalted position in our great faiths – all coalescing and culminating in universal principles with a vindicating crescendo.

These truths I have adumbrated may not be new, but their capacity to resonate in a potentially renascent Sri Lanka is. The Constitution articulates their foundations: It protects the values on which they are premised; it gives to the creativity of lawyers a demonstrable leverage in attacking prospective laws inconsistent with its ethos; it accords to lawyers an expanded field for real fulfilment in areas intruded into by blundering bureaucracy; it equips them and the courts with teeth which are sharp and biting enough to snarl at and chew on visible manifestations of injustice – whether such injustice emanates from within or outside the agencies of the state; whether it is sought to be protected by a statute or regulations or whether it is protected by some perceived rule of the common law which rests on an articulated or assumed premise that is legally illegitimate.

In this missionary crusade to bring about order and organisation this Court is equipped with an explosion of skills and talents. To sustain the momentum, it is necessary to harness their talents creatively with training and capacity building. We will travel towards this identifiable objective so that this Court will have the freshness, potency and an opportunity in this challenge. But a successful pursuit of the potential objectives has its own structural difficulties. But their conquest is a journey, not a destiny. It is a journey which we will undertake collectively with a faith which is optimistic and a temper which is positive.

There are few institutions better equipped than my brothers and sisters, by their enhanced training and by innate experience, to give form and content to and accelerate this journey.

In this journey it is a great privilege to be accorded the esteem of a welcome by the bar and in discharging my duty let me relive with Rabindranth Tagore that noble dream which captures so much of the visionary in a lawyer and a judge:

“Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free:

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action –

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.”

It is a great privilege to be regarded as a friend of the Bar and to enjoy its esteem. May the blessings of the Almighty be bestowed upon all of you. Thank you.